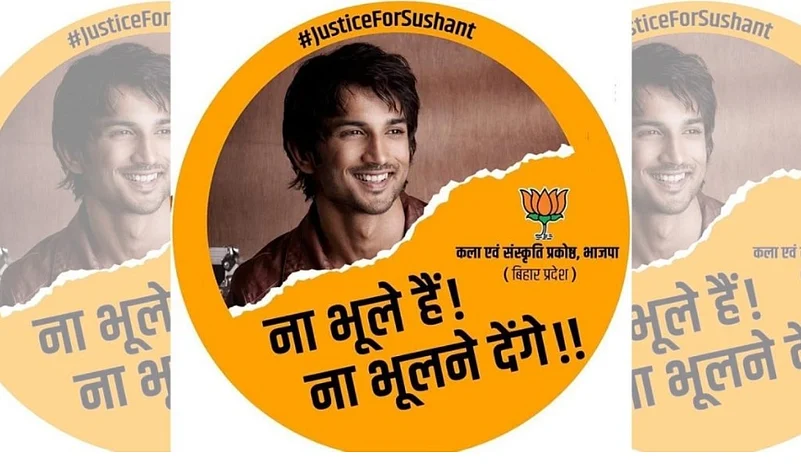

The BJP IT cell recently put out a poster of a winsome Sushant Singh Rajput with a text that reads, “Na Bhoole Hain Na Bhoolne Denge” (Neither have we forgotten, nor shall we let others forget). His death, bemoaned as a huge loss is, in fact, a huge gain for the party, both in Bihar and in Maharashtra. While in Bihar the issue is expected to help them exploit Bihari sentiment, in Maharashtra it may rock the boat of its bete noir, the Shiv Sena.

From the day a political agitation for investigating Sushant Singh Rajput’s death took form in Bihar, one could foresee that Sushant will be forced to be a revenant guest, to help the NDA come back to power in the forthcoming assembly elections in the state. Therefore, it is only natural that the twice useful ghost of Sushant should be granted, what Jacque Derrida says, “the right...to...a hospitable memory...out of a concern for justice.”

What is a ghost? Stephen Dedalus poses this question in Ulysses, and promptly answers it himself. “One who has faded into impalpability through death, through absence, through change of manners.” Not a figure who is entirely unreal, just one who has become a little faint, lacking in physical immediacy. Sushant was not quite as demonstrative about his Bihari roots, in the same manner as say, Shatrughan Sinha. He was certainly not the most recognisable Bihari while alive. But thanks to the never ending campaign (engineered?) by a section of the mainstream media and many groups on social media platforms, Sushant has come to be viewed as the quintessential Bihari genius, cut short in the prime of his career by metropolitan jealousy or the machinations of a deeply entrenched mole acting on behalf of some shadowy mafia.

The assembly elections in Bihar are a few weeks away. When it comes to voting, appealing to the voters in Bihar is pointless. Illusion is the key, drama is the essential requirement while catchy identitarian phrases and startling images should occupy the voter’s entire mental space and nullify the capacity of the mind to think. Le Bron once said that the “art of impressing the imagination of crowds is to know at the same time the art of governing them,” and governing elites have read Le Bon with great care.

For 15 years, “social justice,” a fetish under which all sorts of political fantasies and personal ambitions of the supreme RJD leader were lumped together, but never made explicit, stoked and sustained the subaltern enthusiasm. It helped create some sort of a generic loyalty of a military kind to the supreme leader, ready for the moment when direct action could be taken. Primed by occasional war cries like “Bhura Bal Saf Karo” (a cry to eliminate Bhumihars, Rajputs, Brahmans, Lalas and Kayasths). But the illusion wore off when it was realised that under the garb of “social justice,” there marched the more dogged political morality of power as a means of self-aggrandizement and dynastic ambition.

A competitive offer needed to be put in place to outwit the earlier charmer and the deeply alienated forward caste, still a force to be reckoned with, was ready to be charmed, beguiled and enchanted. The successive NDA government promised to inaugurate the millennium by taking care of present miseries and future problems. It dedicated itself to the task with gusto and Bihar seemed to be well on course to a glorious future but in the absence of a credible opposition and a fawning media it gradually lost steam. The illusion was however sustained by means of emotional stimulating Bihari pride with the help of tremendous media outreach. Together, the accompanying spectre of a return to the nightmare and the undifferentiated chaos of the Jungle Raj kept the people interested in the idea of Sushahsan.

The images of the migrant workers, “the invisible” Biharis, who contribute heavily to the domestic economy by their remittances, undertaking impossibly long journeys back home, on foot shocked the global imagination. Many of these stragglers were reduced to being mendicants on charity of strangers and it blew away even the fig leaf form the already frayed vestment of Bihari pride.

Also Read: A Bollywood Tragedy For Bihar

In this stark setting the most visible achievements of the government-- monuments, museums and mediation centres, drew home the realization that Bihar was so heavily invested in the “past” that our present concerns-- woefully inadequate medical centres and no prospect of getting absorbed in gainful activities at home, seemed to have been neglected. In an atmosphere like this, the illusion of Sushasan as a march to an ever more promising future would have been difficult to sustain. At such a juncture, “Justice for SSR” appears to have just the right proportion of sentimentality, generalised grievance and unfocussed resentment to anesthetize the questioning mind.

Whatever the final outcome of the case, the pot can be kept boiling as long as the poll season. After the elections are conducted, getting rid of a ghost which has served its purpose would be that much easier, because ghosts leave behind no dead bodies, no evidence and no official enquiry. The Biharis would be relied upon to disperse to the four corners of the country in search of jobs, education and health care after having performed their most sacred civic duty.

(The writer is a blogger, social media commentator and former DG of Bihar Police. Views expressed are personal.)