The date when the film Shikara was released—February 7, 2020—may be an innocuous accident, but it acquires meaning when seen in the context of Kashmir, the subject of the film. It was seven months into what was widely seen as the “unlawful abrogation” of Article 370…months that seemed like an eternity, with a perpetual lockdown in place. It was a time when the heavy hand of politics came down on all aspects of life, heavier than before—an evisceration of fundamental rights impossible to imagine for non-Kashmiris, and traced directly by Kashmiris to the fact of being a Muslim-dominated province seeking a political voice. A film that sets out to bring alive the tragedy of the exiled Pandit community, then, was bound to be coloured by the circumstances of its release.

Was that all? Perhaps not. In an atmosphere of growing alienation, the fact is that a film such as Shikara can be used to further the popular Indian animus against Kashmiri Muslims. It may seem an odd thing to say about a film that had a rather troubled reception within certain Pandit quarters—for being too soft on Kashmiri Muslims!—but we have to exit the morass of social media debates at some point and address the real themes. Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s film—“dedicated to over 4,00,000 Kashmiri Pandit refugees”—doesn’t add anything new to the existing populist narrative; instead, it tries to legitimise it. Representation is a complex profession and, especially when dealing with “difference” (here Kashmiri Muslims), it engages feelings, attitudes and emotions, and mobilises anger and hatred, at deeper levels in the viewer.

Bollywood has a particular relation with Kashmir; it has been used as a setting of serene beauty for romance and as the watershed of violence. In the 1960s and ’70s, Kashmir was painted as heaven on earth; Kashmiris were usually gentle, elegant…and apolitical. Soon after the onset of armed rebellion in the late ’80s, the perspectives changed: the depoliticised idyll, with its kind and charming inhabitants, morphed into a dangerous place where the people (Muslims) are nearly always potential terrorists. Trace this movement from Kashmir ki Kali (1964), Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965), Noorie (1979) and the like to Roja (1992), Mission Kashmir (2000) and Haider (2014), all made after the conflict took an ugly shape in Kashmir.

Ek Musafir Ek Hasina (1962)

How does Shikara, a love story unfolding through these chaotic times, compare? Well, it doesn’t labour over the politicisation of the region; instead, it takes an escape route in the individual story of Shiv Kumar Dhar and his wife, Shanti Sapru. In a movie within the movie, we are transported to the late ’80s, the period that transformed Kashmir. The film opens in a time when the fruits of harmony were still being savoured in the Valley. Muslims did not consider their Hindu brothers as ‘minorities’. Instead, they were revered as educated, intelligent members of society enjoying an elevated status. Shiv and Shanti fall in love, and have a typical Kashmiri wedding. Everything seems fine.

For a while. Soon, Shiv’s childhood Muslim friend Lateef Lone’s leader-father (Khurshid Sahab) gets killed by government forces while protesting the rigging of the 1987 elections and reminding India of Nehru’s promise of a plebiscite. Things turn topsy-turvy for Lateef—who dreamed of becoming a cricket star—and for the Valley. Another leader, wearing a Karakul cap, says in an interview, “We can only win a war here, not elections”—suggesting the rise of armed rebellion. Soon, we are shown a transmogrification. Students, instead of joining college, are carrying guns; women are asked to veil their heads; policemen are attacked; Pandit houses are burned down, followed soon by the exile to “hell”—their broken lives in the makeshift tents of Jammu.

There’s also a deeper process of exile, so to speak: from tradition itself. Later in the movie, when Shiv and Shanti are invited to a Hindu wedding, they feel estranged watching a modern Indian-style affair. Reminded of their own traditional wedding, their sense of loss is made keener. For, that’s the real loss for Kashmiri Hindus—their culture, their identity. In their internal diasporas, the older people who lived a large part of their lives in Kashmir carry a deep agony: a nostalgia for their lost homes, their Kashmir experience, their ancestral heritage and values, which they had to leave behind to “save their lives”. An old man in the movie repeatedly says, “Take me back to Kashmir.”

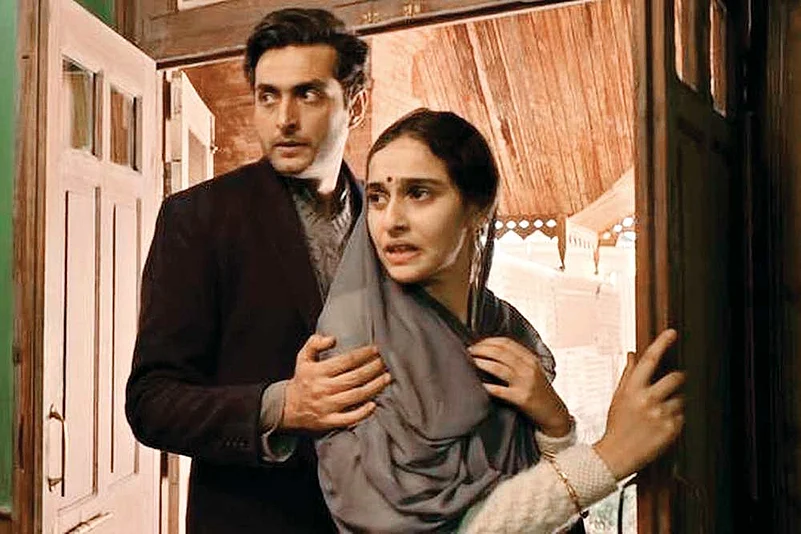

Shikara (2020)

But the fact is, there are narratives and counter-narratives about the incidents that led to the Pandit migration. Jagmohan, then Governor, instead of offering Pandits security in Kashmir, arranged for their safe passage beyond. Muslims were suspicious and thought of it as a conspiracy; rumours were rife about impending doom. As for the displaced Hindus, their exile was first meant to last only a few months—but sadly, the promised return to innocence could never happen. They regarded their “exodus” as the outcome of a well-arranged plan of “Pakistan-backed militants to throw them out from Kashmir”. Many families did not migrate at all—they still live in that brotherhood, an enfolding “Kashmiriyat”, with their Muslim neighbours. But the larger narrative was set; this film too ploughs that simplistic furrow.

Like other films that have romanticised Kashmir, Shikara too functions at the level of myth—celebrating the beauty of Kashmir, creating fragile visions of a harmonious idyll, but ultimately ostracising Kashmiri Muslims for their villainy. In doing so, it offers a literal, denotative meaning that reinforces populist narratives—that Islamist Muslims are responsible for everything happening in Kashmir—thus sidestepping India’s own role in bringing sufferings to Kashmiris of all hues, and evading the question of what prompted those Kashmiris to turn into armed rebels. Within this, there is the sub-theme of jihad and difference.

The film is threaded through with a none-too-subtle Muslim demonology that runs the gamut of partial truth, generalisation, insinuation, disinformation and dangerous propaganda. The filmmaker tries to strike a balance by depicting some Muslims who gave their lives while saving or helping their Hindu brothers, but the motifs that stand out in stark relief are the likes of a guileful Haji, who takes Shiv’s house on the pretext of guarding it, and tells him it’s not safe to return to Kashmir given the war-like situation. The movie explains well Pakistan’s role in using religion to incite Kashmiri Muslims. In a TV report, we are shown Benazir Bhutto speaking of “Maqbooza Kashmir” (Occupied Kashmir) and how “the blood of mujahideen runs in the veins of Kashmiris”. It’s on the other side that the film pretty much pulls its punches.

Shikara was a missed opportunity. Cinema is indeed fiction, but fiction often contains a meta-truth, or is a means of discovering the truth—especially when set against a backdrop of facts and beliefs, it becomes a kind of truth-claim. By setting up a binary, here a Muslim-Hindu one, it constructs a reality that takes us towards a less complex truth aligned to the play of politics, political systems and their agendas.

Also Read:Kashmir 370 Degrees: Year To The Ground

The film ends with the arrival of Shiv in his homeland, so it directly poses the question of Pandits returning to Kashmir. The question has spawned many debates, but most new-generation Pandits, born and brought up in cultures outside Kashmir, would likely balk at the idea of swapping the security of their lives to live in a worn-out, torn-apart place. Kashmiri Pandits have suffered immensely and should now see beyond the exploitation of their trauma for agendas. Since many of them celebrated the taking away of Article 370, which was primarily meant to safeguard Kashmiri identity and sovereignty, they must ask themselves: how would their return safeguard their Kashmiri identity in post-370 Kashmir?

(The writer researches contemporary Muslim fiction in Aligarh Muslim University. Views expressed are personal.)