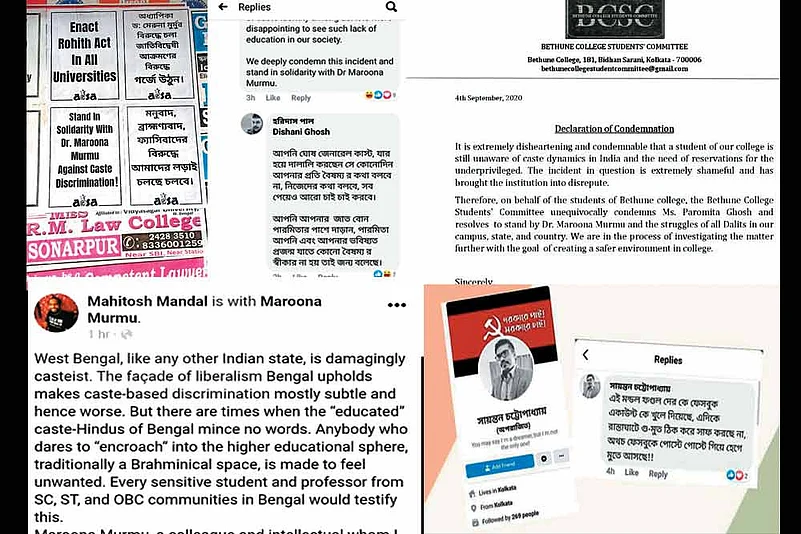

Casteist slurs, heated debates and arguments followed two back-to-back events in West Bengal, revealing a caste-based fault-line that has mostly remained invisible in the state. First, in early September, Jadavpur University (JU) professor Maroona Murmu, who belongs to a scheduled tribe (ST), was trolled online after a Bethune College student insulted and accused her of taking advantage of reservation in education and jobs. Murmu found support from academia, which criticised the casteist remarks. But many social media users stood by the student, Paromita Ghosh, and abused people from ST and scheduled caste (SC) communities for the reservation constitutionally guaranteed to them.

The controversy started when Ghosh supported on social media the Universities Grants Commission (UGC) and the Union government’s decision to hold open-book exams during the pandemic. The JU professor commented that there should be no exams this year—either students be declared passed or let them lose a year. She shared a screenshot of Ghosh’s comment on social media. Ghosh hit back with a Facebook post that said SC-ST people avail themselves of reservation and were now getting paid without having to do any work, a privilege her parents couldn’t afford. Her mother supported her on social media.

“I did not name the madam or attack any community. I said they (those drawing reservation benefits) were incapable of understanding our pain,” Ghosh said in a video uploaded on Facebook. She justified her remarks and threatened suicide if people heckled her or her freedom of speech was curtailed.

Murmu lodged a police complaint against Ghosh under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989. Nevertheless, Ghosh’s Facebook post and video went viral, with many calling for an end to caste-based reservation.

But before this debate died, chief minister Mamata Banerjee’s announcement on September 15 to form a Dalit Sahitya Academy, to be headed by Dalit writer Manoranjan Byapari, triggered another row. Bengali writer Swapnamoy Chakraborty’s sarcastic remarks on the decision intensified the debate around caste divisions in Bengali society. Among other remarks, his demand for a Brahmin Sathitya Academy drew over 1,000 reactions. Most took him literally and either supported him wholeheartedly or tore into him for expressing casteist superiority.

This prompted veteran writers and academics, including Pabitra Sarkar and Bhagirath Mishra, to stand by Chakraborty, insisting that he never had any caste-based bias and that people misunderstood his writing. Subsequently, Chakraborty, who is known in the literary circuit as a rationalist, wrote on social media that he was deeply disturbed by the reactions and clarified that his sarcasm was meant not for the recognition to Dalit literature but for the ‘narcissistic Brahmins’ who would feel hurt by such a recognition.

Both events triggered comment on social media and digital news and literature platforms. “(We) should remain grateful to Swapnamoy Chakraborty. If one counts the ‘like’-‘love’ on his post, the person will get all answers on Brahminism, Leftist politics, patriarchy, the CPM and BJP, and the past and future of Bengali nationality, literature and culture,” journalist Arka Deb wrote on Facebook. His post triggered nearly 200 comments, including first-person testimonies of nearly a dozen people who described the harassment they faced because of their SC, ST and other backward class (OBC) background.

In W. Bengal, SCs comprise 23 per cent of the population and STs account for another 6 per cent, according to the 2011 Census. West Bengal has India’s second-highest number of SCs, after Uttar Pradesh, even though caste-based politics never found a base here. The most important political assertion of people from these castes was in East Bengal in pre-Independence India. However, one reason behind the rise of the SC share in W. Bengal’s population was the migration of “lower caste” people from East Pakistan since Independence.

Chakraborty’s clarification, however, did not soothe Byapari’s wounds. “I was hurt. I had even dedicated a book to Chakraborty. I knew him as a Leftist, liberal person. But perhaps they are afraid to see people from our communities entering their leagues, occupying chairs next to theirs,” Byapari says. Byapari, a rickshaw puller-turned-award winning author, says the recent debates around Murmu and his own recognition did not surprise him. According to him, Bengalis are a shrewd community that has managed to keep caste discrimination alive but invisible.

“In other parts of the country, caste discrimination in overt and visible. In Bengal, due to the influence of the Renaissance and the Left movement, public expression of caste-based discriminatory beliefs was not socially appreciated. Upper caste people would eat the food I cook, would share a table for an adda over coffee, but would also feel threatened to see people from our communities entering their leagues,” Byapari says.

Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury, a professor of political science at Rabindra Bharati University, echoes Byapari. Bengal’s response to the caste issue has been hypocritical, he says. According him, Shri Chaitanya’s Bhakti movement in the 16th century was the biggest reason behind the weakening of the manifestation of caste conflict in the state, while the renaissance and the Leftist movement had their influences too. “However, the message about the annihilation of caste-based discrimination was never internalised. Even those who wanted to portray themselves as secular and liberal exposed their caste and religious biases during private conversation,” Basu Ray Chaudhury says.

He refers to a study he conducted between 1985 and 2007 on the matrimonial advertisements in the state’s largest-selling Bengali daily. The study reveals 94 per cent of the advertisements mentioned caste preferences and it was only in two per cent cases that “any upper caste” was acceptable. “Only two-three per cent did not mention caste as a criterion,” Basu Ray Chaudhury says, concluding that the Left played a nearly insignificant role because they neglected caste identity while trying to focus on class identity. “So, it is the upper caste who form the overwhelming majority of Bengal’s Left leadership.”

***

Maroona Murmu, associate professor, History, Jadavpur University, talks about casteist hatred in Bengal

On Hate Messages: I am used to caste-based discrimination since age seven. We, who belong to SC and ST communities, know what caste-based discrimination in Bengal looks like. We feel it in every aspect of life. The only new thing was the concerted attack I faced. Nearly 2,000 social media users abused me. There were hashtags such as ‘reserved professor hatao desh bachhao’, ‘save merit save the nation’, and ‘down with caste-based reservation’.

On Bengal’s Caste Conflict: The perception that Bengal is free of caste conflict exists because discrimination here does not lead to physical clashes. There is no physical violence, no bloodshed, and people paint a rosy picture. Discrimination in Bengal has been imperceptible but active. I faced sarcastic remarks whenever I wrote for the major Bengali media houses in

support of caste-based reservation.

On The Concerted Attack: First, I suspect an anti-reservation lobby working for years; they prepared the ground for such public insult of people from lower castes. They want to replace caste-based reservation with economy-based reservation. Second, social media has made visible what remained invisible for decades. Comments one heard in classrooms/offices are in the public domain.

By Snigdhendu Bhattacharya in Calcutta