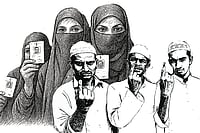

A federal-democracy assumingly is where people of the federating units can fairly exercise their constitutional and legal rights within the ambit of twin principles of self-rule and shared-rule of federalism. The relative successes or failures of democracy essentially rests with its capacity to accommodate the diversity, both in terms of identities and ideologies.

The more peaceful the accommodation is, the better are the chances of laying down strong foundations of the principles of democracy and federalism.

The two incidents in the recent past, one in Mon district of Nagaland and the other at Lakhimpur Kheri in Uttar Pradesh, undermined the core principles democracy and federalism. With these two incidents in hindsight, it seems that both democracy and federalism – the twin essential building blocks of modern nation-state – are backsliding and clawing back. Is it because we have entered into what may be called as ‘new age of rage’?

So what happened in Mon district in Nagaland? On December 4, in an alleged botched up case, the soldiers of Indian Army (21 PARA – SPECIAL FORCES) killed, without provocation, six coal miners and injured grievously two other miners near Oting village in the Mon district. The soldiers killed another seven village folks who protested against the instinctive and indiscriminate killings of the six coal miners.

The next day, one more civilian was killed when the protesters, in retaliation, attacked the Company Operating Base of Assam Rifles and set ablaze its buildings at Mon town. The death toll of civilians rose to fourteen and injured to thirty five during the incident.

The central government, having complete control over the Special Forces, regretted the loss of civilians and explained that it was the case of mistaken identity for insurgents due to intelligence failure. The incident, on the surface of it, appeared to be a casual disposition of signals and information by the security forces, but at a deeper level it begs the real question - can the people of Nagaland afford such kind of public insecurity?

More so, when the north-east regions including Nagaland has a history of internecine murders of innocent civilians and alleged extra-judicial killings by security forces under the cover of Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFPSA), 1958.

The loss of lives simply by the strange quirk of military actions has not only outraged the people of Nagaland but also the larger civil society who seek equal rights for its citizens. To stave off the people’s anger both the central and state agencies responded swiftly. The army instituted a court of enquiry, headed by an officer of major general rank, which will focus on the ‘intelligence’ and the ‘circumstances’ of the ambush. National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) sought a detailed report within six weeks from Union Defence Secretary, Union Home Secretary, and Chief Secretary and Director General of Police of Nagaland.

The Nagaland government constituted a Special Investigative Team (SIT) to investigate the firings and the Nagaland State Crime Police’s FIR on the incident said that army fired with the ‘intention to murder and injure civilians’. Clearly, the pitches in inquires and reports by both the central and the state agencies seem to be at loggerheads. Nagaland people are demanding upfront, among others, the repeal of AFPSA and justice to the bereaved families.

Nagaland Legislative Assembly, on 20th December, passed a resolution relating AFPSA and condemned the massacre. The resolution sought an apology from the central agencies involved in the operations of security forces. The house categorically demanded ‘repeal of AFSPA from the North-East, and especially from Nagaland, so as to strengthen the ongoing efforts to find a peaceful political settlement to the Naga Political Issue’.

Nagaland represents a typical case of ‘asymmetrical federalism’, where in there is a dialectical relations between the federal institution’s administration – both state and centre – and the struggle of ethno-national communities of Nagaland for recognition and protection of their identities and interests. Article 371 A of the Indian Constitution accords special status and wide autonomy, qua asymmetrical federalism design, to the people from Nagaland in terms of the special or religious practices of Nagas, their customary laws and procedures, and the ownership and transfer of their land and resources.

However, the article also confers certain discretionary powers to the Governor of Nagaland, which essentially means direct control from the centre of the state administration. With draconian powers inherent in AFPSA and the Governor’s special responsibilities vis-a-vis state governance, particularly law and order which is the state subject, virtually most of the crucial decisions about public security gets appropriated with the centre.

An innovative all-party governance model, marked by clear absence of opposition, seems to gloss a veneer for state-democracy. Asymmetrical federalism, in case of Nagaland, obfuscates more than it protects the real issues of rights. All political regimes are accustomed to status quo, and hence any demand for restitutions of the rights of the citizens, if violated with impunity, are either seen with suspicion or scorn by them.

In the case of Lakhimpur Kheri district in Uttar Pradesh, violence erupted there on October 3, when the protesting farmers, peacefully, were run over by a high speeding vehicle allegedly by Ashish Mishra, son of Ajay Mishra, minister in the current central regime. Eight people lost their lives on the spot. The Supreme Court, after seeing the tardy investigation of the incident, took suo motu cognisance of the case and reconstituted the Special Investigation Team (SIT).

The opposition and protesting farmers demanded the resignation of the minister. What is shocking about the incident is the vengeful manner in which the vehicle mowed down peaceful protesting farmers. Equally shocking is that, according to the SIT investigation, the killings were a ‘deliberate planned conspiracy’ and not at all an act of negligence or callousness.

The two incidents of gruesome snapping-off of innocent lives bring to the fore the debates and salience of constitutional-morality and fundamental rights as enshrined in our constitution. The recent regression of democracy in India, and worldwide, shows the waning of political and philosophical commitments to rights of the ordinary citizens. Right to protest, in the two cases abovementioned, was threatened by the unfettered power of the contemporary state or its surrogates.

The Indian constitution guarantees certain degree of shared-rule between centre and the state and also certain degree of self-rule by the state administration, particularly in law and order issues. The self-rule, for its smooth functioning, requires certain degree of decentralisation. This framework would necessarily create conditions for realisation of fundamental rights. Violation of right to life, in both the case, requires justice and restitutions.

Any deviation from the path of justice and restitutions would strike at the very root of the basic structures of the constitution.