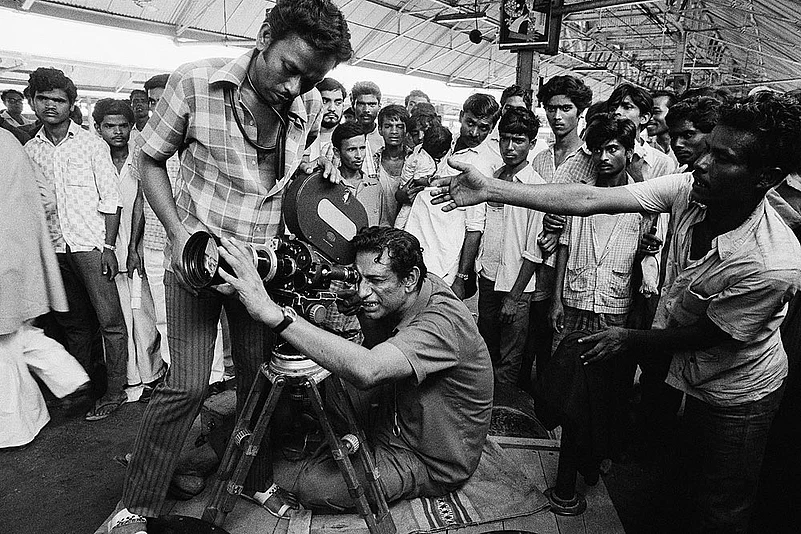

Hopeful but exhausted fresh graduates are running from pillar to post for few coveted jobs. They are struggling the whole day, barely managing to stand while traveling in over-crowded buses. However, they have to brace themselves for the possibility that their individual job application maybe lost in the flood of thousands of similar job applications. These scenes which feature in Satyajit Ray’s films, Jana Aranya and Pratidwandi, portrayed the socio-economic reality of West Bengal in the 1970s. Fifty years on, they still resonate all around us.

Both these films feature educated male protagonists- Somenath in Jana Aranya and Siddhartha in Pratidwandi- who are desperately searching for a secure job in the formal sector to support their families. But some of their potential employers had already selected the candidates for the applied post. Nevertheless, they went ahead with the interviews asking questions which were irrelevant to the prospective jobs. In some other cases, the employers were on the look out for docile employees who would choose not to raise their voices against the authority. This is why Siddhartha loses out on a job, being labelled a ‘communist’, when he argues that the display of courage by the Vietnamese peasants during the Vietnam war was more significant an event than the moon landing. The farcical nature of such interviews and the subsequent rejections drained the protagonists of all hopes of ever getting hired.

Such a scenario is currently prevalent in our economy where over 35 percent of educated youth are unemployed (Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017-18). Concurrently, there has been a fall in the overall labour force participation rate along with an increase in the unemployment rate. Such a situation indicates what we know as the ‘discouraged worker effect’ in economics. This phenomenon is caused by the exasperation felt by both Somenath and Siddhartha following their continuous rejections. The dismal situation of formal sector jobs has been depicted in yet another film of Ray- Mahanagar. Subrata, the female protagonist Arati’s husband- loses his job and remains unemployed till the end of the film, in spite of actively looking for employment.

This existence of a large pool of educated youth and a shortage of formal sector jobs, as observed in each of these films, is an intrinsic by-product of the functioning of capitalism, especially through privatisation. Comparing this with today’s economic situation, we see that intensified privatisation has led to a forty-five-year high unemployment rate during 2017-18. Even during the current pandemic, private sectors are either slashing the salaries of their employees or laying them off, in spite of earning profits. This is worrying since it is difficult to get a new formal employment. This situation can only be predicted to aggravate in the near future, with the incumbent government serving the capitalists’ interest of maximizing profits through cheap labour, by pushing for greater privatisation of core sectors of the economy, and by diluting labour laws.

Female characters in these three films manage to find a job in order to support their families. While Arati gets hired as a saleswoman selling household appliances, Pratidwandi’s Sutapa works as a secretary to a male boss. These are typically ‘feminine’ jobs in the formal sector. On the other hand, Jana Aranya’s Kauna is compelled to resort to sex-work to supplement her family’s low income. This portrayal of engagement in economic activities out of desperation is analogous to what is often referred to as ‘distress-driven employment’ in Economics. This has been a common observation in the case of females in the Indian economy.

However, household dynamics concerning the women do not change even after they become the primary bread winners. They are constantly met with explicit or implicit disapproval of the family members, especially that of male members. This patriarchy within the household premises which keeps the man in the dominant position is reproduced in the work place and is manifested in the segregation of the job market, on the basis of gender. For example, in the occupation of nursing 84 percent of the workers are female, and in that of pre-primary teaching 83.29 percent of the workers are female; whereas 70 percent of the workers among health professionals including doctors are males, and among college, university and higher education teaching professionals 61.79 percent of workers are males (PLFS 2017-18).

Apart from such instances, there is blatant portrayal of patriarchy within the household, where household chores are exclusively the responsibility of the women. Somenath’s sister-in-law Kamala is seen throughout the film covering her head, and meeting the culinary demands of the male members of the family. In the same film, we get a glimpse of Somenath’s friend’s low-income family where the daughter is seen helping out in the kitchen while her brother is studying. Similar scenario is observed in Mahanagar, where Arati’s sister-in-law is being trained for household work such as cooking.

Such division of labour based on gender is still prevalent in our households. According to PLFS 2017-18, of all the people engaged in domestic duties and associated activities, 98.1 percent were women. Thus patriarchy, implicitly and explicitly, plays a crucial role in thwarting women’s aspirations.

These portrayals of the characters and their respective situations reflect a larger political undertone, in all the three films. The political situation of West Bengal in 1970s was extremely volatile, where political slogans and graffiti on walls were ubiquitous. In Pratidwandi, Siddhartha’s younger brother was involved in radical politics, and considered revolution to be the only way out of the current system. However, such efforts were destroyed systematically by the State. The hope for revolution soon gave way to despair as the street graffiti were blackened. This despair is manifested in Siddhartha himself, who was once active in student politics but ends up as a salesman outside Kolkata against his wishes in order to look after his family. The inability to secure a formal job pushes Somenath to start a business which requires him to sacrifice his morals and ethics. Also, in spite of her newly gained bargaining power and her financial contribution to the family, Arati’s job was considered secondary and a substitute to her husband’s job.

The despair shown fifty years back is felt across the country today, where we see systematic witch-hunt of poets, writers, students, professors, activists and trade unionists. With resistance meeting brutal state repression, much like it was in 1970s, the only liberation from the oppressive machineries of capitalism and patriarchy can be envisaged through Siddhartha’s words: “Revolution is the only way out.”

Annesha Mukherjee is an MPhil Research Scholar at Centre for Development Studies (JNU), Kerala.

Satyaki Dasgupta is a Graduate Student at Colorado State University, Colorado, USA.