Sometimes, a photograph arrests your attention and holds you in its thrall. Right at the moment of your first encounter with the image, you feel it is iconic. You gaze at it in the knowledge that this is a picture that captures a point in space and time, a picture that is simultaneously history and the future, a picture that marks the shape of things to come. It heralds the arrival of something new. It pulls together something timeless.

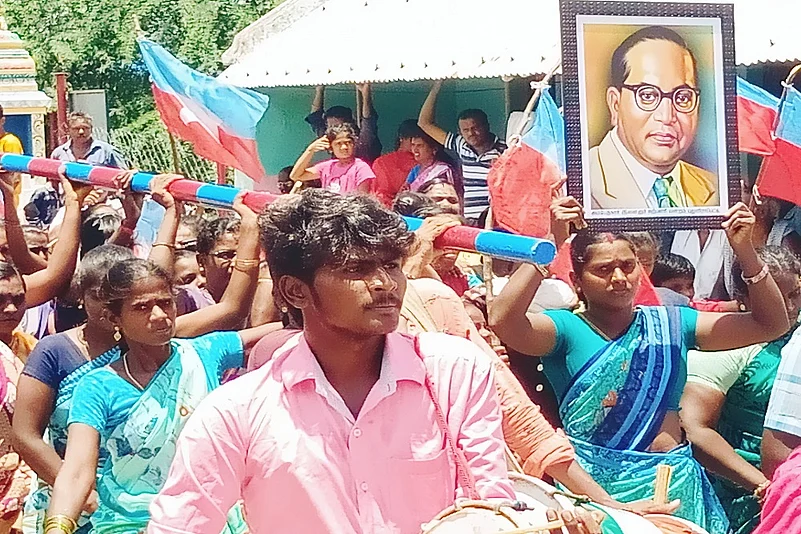

I was in Belgium when I first spotted that sun-drenched photograph on Twitter—a proud woman wearing a bright blue sari, holding high a framed portrait of B.R. Ambedkar, and behind her, other women carrying the red-and-blue flagpole painted in the colours of the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (Liberation Panthers Party, in short, VCK) in their arms, decked in bangles. It was September 6. Peering from behind the sea of heads and four VCK flags were two young children. There were two middle-aged men, both onlookers. Bang at the centre of the picture, without appearing to intrude into it, was a young man in a pink shirt beating a drum with an intense, faraway look in his eyes.

In this celebratory moment, he was there but not quite. Like a war-drum, his instrument spoke for him—it kept count, never tiring. You could hear the thrum of the Panther slogans. The energy of the image of a brave, unfazed woman carrying Ambedkar’s image would make you sit up and applaud. She was looking directly at the camera, at us, as if she was beckoning us to come and witness her heroism.

Caste conflict in India’s southern state of Tamil Nadu is not new. In fact, it is one of the homegrounds of political assertion of lower castes in India. Over the decades, though, as each Bahujan layer has inhaled a whiff of political freedom, they have predictably peeled off from the base and floated above, to attach with the upper caste layers, leaving behind the Dalits at the bottom. An electoral ally of the ruling DMK in the state, VCK has, over the years, come to become the focal point of Dalit assertion, inevitably leading to tensions.

Of late, across rural Tamil Nadu, this tension has coalesced into an emerging social boycott of Dalits by all other castes who come higher in the social hierarchy. With rural Dalits being largely landless, this has pushed them to the wall, and elicited a pushback—in the form of a desire to assert Dalit presence in public spaces through the hoisting of the VCK flag and prominent display of Babasaheb Ambedkar’s photo—something, it would appear, the oppressor castes are loath to allow. Sometimes even at the cost of their own public displays of caste pride. Talk about cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face.

On that sultry September morning, the Dalit women of Pudu Viraalippati, a tiny village in Alathur, Perambalur district, who bear the brunt of the everyday marginalisation, braved the threats of caste Hindus and arrest-warnings of police to claim their democratic right to hoist the VCK flag.

When I returned to India, I went to meet these courageous women.

The VCK flag, which has come to symbolise the aspirations of many, was first introduced on April 14, 1990 in Madurai by Tholkappiyan Thirumavalavan, the founder-president of the-then DPI (Dalit Panthers of India). It has a white, five-pointed star at the centre of a blue-and-red striped rectangle. The blue is dedicated to the ideals of Ambedkar, the red—unique among Dalit political flags in India—signals the party’s commitment to Marxism and the revolutionary path, while each of the five corners of the star represent a core demand—caste annihilation, women’s liberation, proletarian liberation, linguistic/Tamil nationalism and anti-imperialist struggle.

The VCK flag welcomes us into Pudu Viraalippatti on my visit, on September 25. It stands right across the bus stand—the only flag visible in the horizon.

Three weeks after their heroic face-off with police and oppressor caste protesters, I meet the Dalit women of Pudu Viraalippatti in the early evening, after they have returned from the fields. It’s a busy hour for them, when they cook rice for dinner. But they have agreed to accommodate this interview. The entire village gathers at the Mariamman temple in the cheri (Dalit locality), where women do most of the talking.

I listen, learn, and I am left enraged—Dalits, numbering 200 households, are vastly outnumbered by the 800-strong oppressor castes—Naidus, Chettiars, Vellalars. As primarily landless farm labour or small land-holders, they are inevitably dependent on caste Hindus for their livelihood. Even little children of oppressor castes call Dalit elders by name, without the customary suffix of respect. Dalits are still not allowed to enter the Nallendraswamy Perumal Koil, a temple that comes within purview of the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Board; nor have they ever been able to take any of the 15 acres of land belonging to the temple on annual lease for farming. There are no sanitation facilities—children have to walk a kilometre to relieve themselves. For older children, the bus to the nearest government school at Chettikulam comes at 6.30 am, and again at 9.30 am, so they leave home at six in the morning and return by six in the evening. Several faint at school because they haven’t been able to eat breakfast. Children of oppressor castes escape this fate—the fathers own bikes to drop and pick up their children. In most cases, their children are enrolled in private schools. Out of the 95 Dalit families who were allocated land pattas in 1995 under the Panchami land scheme, 37 have no access or even footpath to reach their plots. Dalit men insist segregation exists even in the common cemetary, and that caste Hindus enjoy more facilities.

The Dalits have chosen to discard their vacillating political affiliations with one or the other Dravidian giants, and embraced VCK. It’s the inevitable resistance against ongoing atrocities, unchallenged for centuries. In the aftermath of the Panthers hoisting their flag, the oppressor castes have doubled down on their hatred. No sooner than the blue-red flag had gone up the pole, that caste Hindus of Pudu Viraalippatti stopped employing Dalits on their lands. The aim is textbook casteism—deprive Dalits of their livelihood.

The demand of Dalits to the common lands, to hoist the VCK flag they have made their own, has its roots in cultural connections of that space to their everyday practices. “In our marriages, this is the spot from which we welcome the bride in a procession. At the summer festival Chithirai Thiruvizha, this is from where we bid farewell to the men who set out on a rabbit hunt. This is settled tradition. That land belongs to no one. It’s ours as much as anyone else’s,” says Chitra, one of the women who led the flag hoisting procession.

(All names changed to protect identities)