After two years of struggling with the viral apocalypse, an oft-asked question these days is—will the world ever return to normalcy? Normalcy, though relative, is the state of being usual, typical or expected. For Kashmir, what is normalcy beyond the viral apocalypse? The bigger question for Kashmir would also be if the pandemic is the real apocalypse? And if, the apocalypse that is real in Kashmir, can ever end, even after the pandemic does.

For Kashmiris, normalcy has ceased its relationship with the comfort or discomfort of routines. It is not in the life beyond social distancing, jostling for the piping hot bread from the corner bakery or that cup of tea from the roadside stall. It is not going out or staying inside with or without the mask. It is not the laidback joys or tribulations of everyday.

In the verdant necropolis of Kashmir, people have a fraught routine that counts as life. It is a Kashmiri normal, if you will. Broken down into chunks at checkpoints, crackdowns, frisking, detainments, crossfires, fake encounters, arson and beatings. Even during the pandemic, despite the United Nations calling for cessation of violence in conflict zones, the government of India did not stop its counter-insurgency operations. For Kashmiris, the threat of virus seems small, even when fatal.

What does the Indian State count as normalcy in Kashmir? Normalcy is a statute imposed by the Indian State. It is a bunch of variables, ranging from an “event-free street”, “unbroken curfew”, “only one killing”—to name a few that are engineered to unfailingly project the acquiescence of Kashmiris in some measure. The government then deploys these results as a measure of Kashmiri endorsement for India and its policies, however repressive. It is almost saying that the bird likes the cage, a gilded one at that.

During the military operations of August 2019, India’s Supreme Court directed the government to “restore normalcy” in Kashmir “keeping in mind the national interest and internal security”. How is normalcy restored in a state of exception with a pandemic looming on the horizon? Despite the extreme communication clampdown, a few videos surfaced on social media. They showed Ajit Doval, the National Security Advisor, eating biryani on the roadside with a few hand-picked Kashmiris. Where on earth in the strictest of curfews is biryani cooked to be eaten on the street with random lackeys. Doval reported there was peace and normalcy in Kashmir; the situation was “event free”. A summation of brutal curfew in which a woman in labour had to walk 26 miles to reach a hospital and the crisis received so much international attention that even the medical journal, Lancet, wrote an editorial. Normalcy, in the theatre of Kashmir, is thus a performance, a spectacle. It does not need to exist. In a post-truth India, a columnist managed to say that media houses to highlight the supposed “calm” and “normalcy” that is prevailing in Kashmir despite the government’s tumultuous announcements withdrawing not just special status for J&K but its statehood too.” But normalcy was a diktat even before the BJP militarily stripped Kashmiris of the last vestiges of its territorial sovereignty. Normalcy in Kashmir is not a state of life, but a condition of subjugation. It is woven into every movement. Manufactured in a post-truth India, normalcy in Kashmir is a shiny factoid.

ALSO READ: Song Sung Blue: The End As A New Beginning

***

we exist only on paper,

till papers exist.

when they burn

in a fake encounter

we will cease, again-

for real

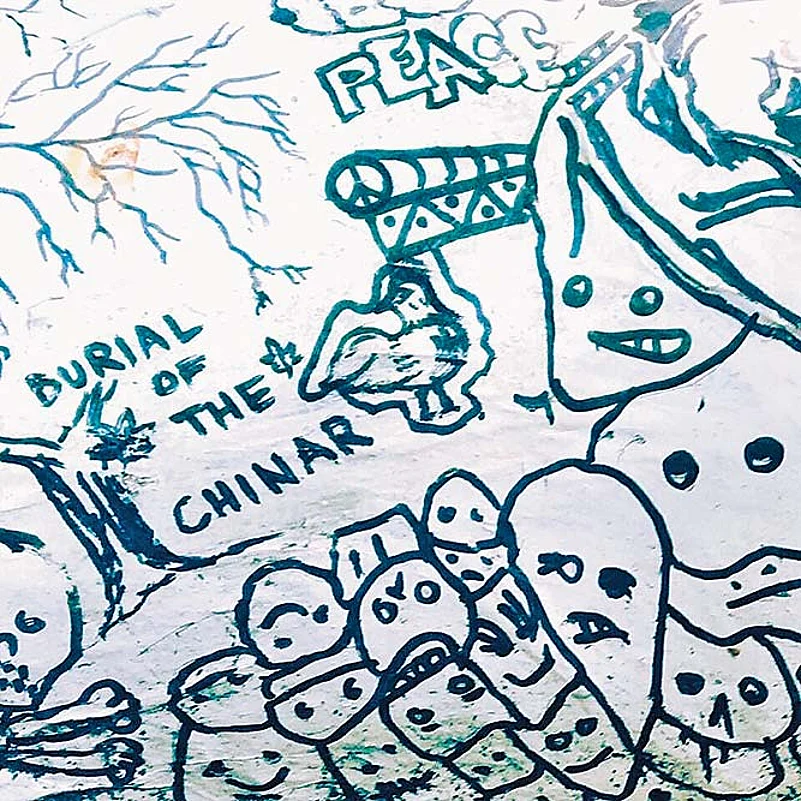

In the old ramparts of Srinagar city, it has become most normal for an aging patriarch to obsess over gathering all documents connected to his property. Since the domicile law was changed, his anxieties around the influx of settlers from across the Pir Panjal have taken over his life. He routinely calls to warn his relatives to secure their property papers and buy fireproof safes. Between not knowing when the military operations ended and the pandemic lockdown began, the ailing old man only has access to news. He cannot keep up with the laws that are being changed fast, specifically ones pertaining to land. The story of a Palestinian couple standing in front of their old home while a Jewish settler family looks out from their house haunts him. He is sure of becoming homeless in his own homeland. “The day is not far, I pray it never comes, but we are at the receiving end here, just like these people [Palestinians],” he says.

Incidents of evictions on one pretext or another, occur almost everywhere. Directly ruled as a Union Territory, all laws in Kashmir are being changed or replaced. Changes in land laws are direct, and some are unfolding incrementally. The varying iterations, gradations and categorisations of new laws, especially ones pertaining to land, will have grave impact on the future of native Kashmiris. First, the domicile status was assigned to non-Kashmiris only fitting certain criteria, and agricultural land was said to be protected. Now, the conversion of land from agricultural to non-agricultural purpose is permitted and can be used for businesses, without the need for construction of buildings or domicile status. From the Kashmiri vantage, this is not development but an open invitation for their dispossession and plunder of the local economy. Not that people dare protest this for the fear of persecution, which is increasing.

Kashmir is a mountainous region and land is limited. Agricultural land has already dwindled. Area currently occupied by the Army and paramilitaries, if aggregated, would be the size of Dallas, Texas, and it is growing. New laws ensure the process for Indian defence ministry to acquire land is smooth. All this through simple bureaucratic orders with zero consensus of Kashmiris. More areas have been designated to be taken over by the troops. These places are not empty but neighbourhoods where people have lived for centuries. The famed pencil village named Ukhoo is set to become a paramilitary base. Kashmir’s own Sheikh Jarrah, where the community is distraught having nowhere to go.

ALSO READ: The Four Horsemen Of Apocalypse

***

we are silenced

not silent

we have tulips

waiting to bloom

and

graves to fill

While the world awaits a post-pandemic life, Kashmiris are counting ways in which they will be dispossessed. Kashmiris are lamenting pashmina will be woven in Uttar Pradesh, and saffron will grow in Kerala. Such fears are antithesis of Kashmiri nature, which is open and futuristic, but have been instilled and exacerbated by open political, cultural and economic hegemonic forces, unleashed by the Indian government on them. Mixed with fear of judicial persecution and impunity of Indian troops, people are silenced. Censorship has been institutionalised and human rights defenders are persecuted.

The state of “normalcy” in Kashmir is being stage-managed, but things are also getting out of hand. Despite the fear of arrest, women recently came out on the streets when they witnessed the day-time fake encounter of three boys accused of being militants. This incident was close at the heels of another fake encounter, where the Indian government finally had to relent and exhume the bodies of men that Indian troops killed, accusing them of being militants and militant aides.

ALSO READ: Meowdi: A Short Story by Perumal Murugan

Pandemic or not, Kashmiri normalcy is a brief interruption lived between guns and bunkers. The sorrow in Kashmiri normal is apparent in congregants crying for masjids to be opened for prayers. This, especially for the grand mosque Jama Masjid, which is the hub of Friday prayers and protests in Kashmir. Kashmiris are not ready to believe it is just Covid restrictions. “All places of worship of different religions have been opened, while on other, Jamia Masjid Srinagar is being subjected to vengeance,” says a worshipper.

Fear of annihilation, existential, cultural and political, has long been a forced normalcy in Kashmir. Beyond the pandemic, between pleading for the return of killed bodies and persecution that does not ignore even a dissenting emoticon, Kashmir seems to be edging into the normalcy of a graveyard.

And yet, despite his anxieties, the old man resorts all his cares to “hyermisshawale” (in the protection of the one above). He says Allah is the best planner. He is indeed speaking for all of Kashmir, where prayers have always been a way of protest.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Gilded Cage")

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Ather Zia is a Kashmiri poet and writer who teaches anthropology and gender studies at the university of Northern Colorado at Greeley, USA