One day, historians will call this the Gelded Age. The earth was to have become a neon-lit orchard—flat, endless, endlessly networked and buzzing. Like a super-extended Dubai or Singapore. Only the ripening of fruit was awaited.... That’s when the blights struck, in a rapid series of crippling blows, beginning 2008. In Davos last year, they were still indulging their hubris, talking Globalisation 4.0. But now, at the grim daybreak of a new decade, the promised land looks void ab initio: shaky and paranoid at the centre, rough and uncertain along the margins.

That flat piece of ceramic appears warped, and the prophets are falling off the edges—there goes Fukuyama, and there Friedman, along with all that tropey economics. As we embark, blindfolded, on the Timid Twenties, India marks its first quarter with the largest repatriation exercise it has ever done. Indians are being brought back from some 31 countries, by air and sea. And the densest lines on this ragged march of history will be traced across what was till the other day a Gilded Corridor...stretching from Kerala, a jobless tropical paradise, to the Persian Gulf, the other end of the rainbow where the pot of gold was.

It may not be a full stop to the story of the diasporic Indian, the NRI, the Raj and Simran of DDLJ, the global desi with fine taste in cheese. But it is certainly a semi colon, an ellipsis...a dream interrupted, very rudely. The literary stars will still hang in there, chronicling their elegant anguish—it’s the dregs that will fall back. India is dignifying this return exodus with Sanskritic names like ‘Vande Bharat mission’, lending a dab of nationalist pride. But the future looms fairly grey and sobering. What will lakhs of them do back home? As we speak, they are tracing a Trail of Tears—some 67,833 evacuees from El Dorados around the world. The most vulnerable among them only marginally better off, in degree of distress, than those internal migrants marching on India’s highways. In a Covid-hit world, they are all flying in to a stir-crazy home front apprehensive of what they represent: disease, disorderliness, a dead weight on the economy. Over a third of those, 25,246 in all, are headed to Kerala. But that number is only a fraction of the five lakh non-resident Keralites – a figure that is itself just the tip of an ‘iceberg’ that will eventually hit the tens of lakhs as the caravan dust settles –registered with NORKA-Roots, the nodal agency for NRK affairs. Several more have been sent on unpaid leave, had wages slashed or withheld, or just shunted out without notice.

The sea is choppy: the same sea that, over two millennia ago, linked Arabia and Kerala on the Incense Route. Frankincense and pepper flowed between what the Romans called Moscha Limen and Muziris—a dotted line between ancient Oman and Malabar. But now the winds bear intimations of despair, hastening a long-predicted end to one of the world’s most compelling rags-to-riches stories. Policymakers and migration experts are chary of calling time on it, but the common Malayali feels it on the skin. It’s been a saga in the sun—over half-a-century of oil, blood, money, sweat, consumerism and tears—an orientation of the land that led to every fifth home in Kerala being a ‘Gulf house’. Has the sun finally set on that endless dream?

A favourite aphorism in the state goes, ‘When the Gulf sneezes, Kerala catches a cold’. The Arab could trust the Indian to keep a secret too—“al hindi ma yikhabar,” old Muscatis would say. From Kachhi old-timers, “Al Hindi” had come to mean the new Malayali professional/underclass. The depth of the linkages, as often fraternal as they were servile, may have shallowed but still held true across all of West Asia’s upheavals: endless war, recession, ISIS, and localisation regimes (like Saudi Arabia’s nitaqat policy that hit the hardest). The numbers spoke emphatically: six GCC nations, says the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) at Trivandrum, account for close to 90 per cent of all Keralites overseas! It also pegs the diaspora at 21 lakh. So nearly a tenth of Kerala’s 3.34 crore population lives outside India (which is what led to those jokes about the Malayali tea shop on the moon). And each NRK supports four people back home. By 2020, diasporic Kerala was to hit a short-term high of 20-25 lakh on account of (re)migration spurred by diminished savings as also the loss of lives, homes and livelihoods to the devastating floods of 2018-19. Then COVID-19 happened.

Arrival lounge A stranded Indian returns from Doha.

The wave had otherwise been ebbing. The Kerala Migration Survey (KMS) 2018—the eighth in CDS’s series of labour flow studies—reckons one out of every five households in Kerala is home to an emigrant—down from about one in four in 2008. The graph for 2013-18 showed a dip of roughly three lakh emigrants; eleven of the state’s 14 districts registered a negative growth rate at least once in that span. And returnees over that period numbered a considerable 12.95 lakh—60 per cent of total emigrants. So one in seven households has them: a social fact as much as an economic one.

But such portents dimmed in the afterglow of inbound remittances, named “blood money” by KMS co-author S. Irudaya Rajan. And why not? It’s been Kerala’s lifeline. In 2014-18, it rose from Rs 71,142 crore to Rs 85,092 crore—accounting for 35 per cent of Kerala’s GDP and 39 per cent of its bank deposits over that period. Over Rs 30,000 crore of that, says CDS, flowed into households: towards savings, paying bills and school fees, repaying debt, funding weddings (including dowries), building/buying a home, maybe adding that second storey. Entrepreneurs started businesses, the faithful gave tithes, everyone bought a car or gold. Giant ad hoardings for marble and granite flooring, fancy condos and gold—lots of gold—dotted Kerala’s paddy-fringed highways. All of which fed the enduring characterisation—despite some sensitive portrayals of their lived-in realities in film and literature—of the ‘Gulf Malayalee’ as both tragic figure and showy parvenu. The vitriol directed recently at Corona ‘super-spreaders’ in Pathanamthitta and Kasargod typified the baseline social response to a perceived sense of NRK ‘entitlement’. CM Pinarayi Vijayan had to weigh in with an admonition for it to cease.

But now, the hype about remittances crossing Rs 1 trillion sounds sonorously empty. The World Bank says the crude oil shock will choke flows from the UAE and Saudi Arabia—the two biggest headsprings for Kerala. State finance minister Thomas Isaac reckons Kerala’s economy will shrink by 10 per cent, with nearly every sector, including the milch cow of tourism, expected to be “devastated” by the pandemic. Rajan expects remittances to dip by 15 per cent in 2020. Prolonged abstinence from the state’s twin vices—liquor and lottery—will exact costs as well. It’s this cheerless landscape that awaits a possible mass influx of muddled, panicked returnees.

For decades, though, those headsprings in the Arab oases have watered Kerala, and altered its social landscape—creating a viable, buzzing middle class out of a vast former serfdom, caste groups like the Ezhavas, newly freed by Communist land reforms but jobless. (Their move en masse to a capitalist mecca being a matter of no small irony.) The Gulf was also a singular factor that helped the Mappila Muslims of north Kerala level off some historic socio-economic disparities. A lot of Malayalis took on blue-collar jobs (proverbially, things they would NOT do in Kerala); young Mappilas mostly stuck to the same small-scale businesses as back home: convenience stores, textile shops, electronic shops, local supermarkets, hotels. Some scaled up auspiciously. Out of rural coastal Thrissur, for instance, came the LuLu Group’s M.A. Yusuff Ali, the billionaire who now owns the Scotland Yard building, a stake in the East India Company, part of Cochin airport, Asia’s largest mall....

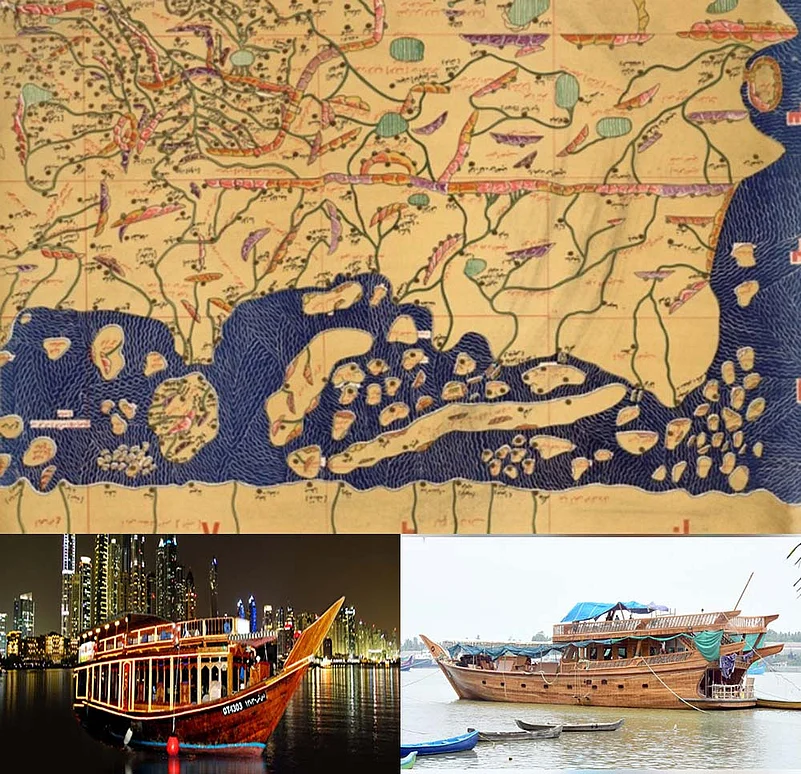

A curious and colourful Genoese world map from 1457. The depiction of India and much of Asia is clearer—the imagery is based on descriptions by traders and travellers like Marco Polo and Niccolo dei Conti. Kerala’s Uru (Below right) and Dubai’s Dhow—the boats that carried goods between Malabar and the Arabian peninsula in the old days.

The returnee story also contains, in a disembodied way, those who won’t be back. “When the money doesn’t reach, that’s when the questions begin,” says Shafeek Madavoor, who would have been on one of those home-bound flights if he could afford it. The 38-year-old security guard (and part-time lyricist) has had time to indulge his partiality for the poetry of Aimé Césaire, the Caribbean theorist of negritude who had a thing or two to say about exile. Shafeek has been holed up in his hovel-like room in Dubai, which he shares with six others, for nearly two months without “even basic salary”. It’s the bitterest sort of déjà vu. An earlier stint in Dubai had left him bed-ridden with pleural effusion. “I served that company for seven and a half years, but they still deducted 4,000 dirham (over Rs 80,000) from my dues when I had to return to Kerala for treatment. Later, my doctor said I would’ve died of pneumonia had I waited any longer,” says Shafeek, who takes his surname from Madavoor village, Trivandrum district.

Why go back then? “Because there’s nothing for me back home. Do you think I’d be here if there was any other option?” he asks. Like thousands, Shafeek is trapped in a cycle of indentured servitude. “I have to repay loans for my treatment, also the hundi.” That last is an informal money order middlemen use to pay the ‘kafeels’, the Arab sponsor: the much-criticised ‘kafala’ system of immigration suretyship.

A half-hour drive from his home is Sonapur, the ‘city of gold’ that best sums up the Dubai mirage. Once a “Dharavi-like slum” in the badlands housing labourers from across the world, and mostly Malayalis among them, it has had both a literal and figurative facelift. Now these gilded dorms also room migrants from elsewhere in India. The impetus for this renovation came in 2013 after Dubai was awarded the 2020 World Expo. That “hot air balloon” was almost meant to burst, and the “Men behind the curtain” issued an edict to the workers that essentially said, “Click your heels together three times and go home”, says Nida*, a migration watcher based out of Abu Dhabi. In this land of Oz, workers make convenient straw men when things don’t go to plan.

“If I could, I would. For all its faults, there’s no place like home, my beautiful country with its high sesame shores,” says Shafeek, dipping into Cesaire, seeking solace in poetry. Across the border, Shaji* in Muscat finds it in drink. The proscription on alcohol during Ramzan notwithstanding, the 27-year-old from Kottayam needs the sauce to forget about his pregnant wife back home. Having been laid off and overstayed his visa, Shaji is an ‘illegal’. His days are now spent in ‘Bombay Gali’, a chawl-like warren in the migrant hub of Ruwi that houses undocumented workers from the subcontinent. Between the backalley cricket under clotheslines, the cut-price Bollywood shows (hence the name) and the ‘katakat tawa’ grub at the Balochi hole-in-the-wall—a culinary call to prayer for the Gali’s denizens—“it is not a bad life if it were not for the threat of prison hanging over my head”, Shaji says. Raids to catch ‘boat people’ (who come by dhow mainly from Gwadar in Balochistan) also net those who overstay. Shaji has dodged them so far; the cops are focused on the pandemic. “The child is supposed to be my Eid gift. Now, I don’t know when I’ll meet them,” says Shaji. He hasn’t registered for repatriation since that would “defeat the purpose”. “I’m here to make money for my family, not spend it (a seat on the Kochi flight costs Rs 14,000). I won’t leave till I have sent back enough to pay our debts and build a house...unless they catch me. Where will I find well-paying work back home?”

It’s a story P.M. Jabir hears “maybe 150-170 times a day” in his Muscat office. The Thalassery native is a director at the state government’s Kerala Pravasi Welfare Fund, but for nearly four decades, Muscat’s workers have known him as Jabirka (Big brother Jabir). “Thousands of daily-wagers in the souks, farms and factories have been out of work during the lockdown as their sponsors have no income. Luckily, during Ramzan, they get biriyani for iftar, even so their condition is pathetic. Some 10,000 undocumented workers should go home...they can’t because of various reasons, including the kafala system,” says Jabir. (The sponsors withhold passports, illegally of course, till ‘dues’ are cleared). He speaks of some 22,000 registrations on NORKA’s repatriation portal and “at least 50,000” more with the embassy.

Returning to Kerala can be its own rite of passage. Sujathan, an Oman returnee who runs a seafood shack in Kovalam, sees himself as one of the lucky ones, having only been cheated of an investment once. One district over in Punalur taluk, Kollam, P. Sugathan, who’d built his seed capital as a mechanic toiling for over three decades in Oman, committed suicide in February 2018 after his entrepreneurial dreams got caught in the usual cobwebs...bribes, intimidation, work disruptions by CPI youth activists. The commonalities in their names, emigration history and experiences have stuck with Sujathan. “In the Gulf, we learn to trust our own because there’s safety in that. Here, that makes us easy pickings for cheats and corrupt officials,” he says. The suicide of Nigeria-returned Sajan Parayil in Kannur last June framed the issue in stark relief: he’d risen from a Rs 15 weekly wage labourer to a Rs 15 crore businessman, but was finally strangulated by municipal-level red tape. Kerala’s suicide rate is 23.5 per cent, a robust 13 percentage points above the national rate. That would be a space to watch as lakhs of youths stare at a futureless vista—with the one guarantee of a viable life, the Gulf, taken away.

It’s just one of Kerala’s many dichotomies: a vibrant start-up ecosystem, a proactive IT department, but also that old reputation for militant trade unionism. The World Bank’s ease-of-doing business rankings place it consistently near the bottom among India’s states—21st in 2018. “Despite its love of consumerism, Kerala’s polity is decidedly left-of-left. There’s a certain distrust of market forces and entrepreneurship,” says D. Dhanuraj, chairman, Centre for Public Policy Research, Kochi. If anything, it’s Communist strongman Pinarayi who can pull off a reversal of that, he feels. Pinarayi does wield an orderly hand when he wants. For all the usual Indian bureaucratic faults, schemes for returnee welfare—including for collateral-free loans of Rs 10 lakh—are hitting 100 per cent utilisation. The irony isn’t lost on bank officials whose default position used to be the bent-over-backward asana for wooing NRK investments.

Pan the camera to Malappuram, the district that finds itself frequently picked on for being Muslim-majority. One in three households here is an NRK household. It boasts the highest number of migrants, about 4 lakh, and gets 21 per cent of Kerala’s total remittances. But the flow of returnees is the highest too—nearly a quarter of the total, with about one in four households having a returnee. Naturally, some are worried. Not Pratheesh Mullakkara, secretary of a 16,000-member pravasi welfare cooperative society. “Visit our Up Hill head branch. You can’t miss the bakeries, poultry shops, dairy farms, beauty salons, teas stalls and tailor shops we helped them set up. Last year, we exhausted our Rs 5 crore fund within the first two months itself,” he says. Ajith Kolassery, NORKA recruitment head, says due diligence, government support and follow-up—“a capital outlay of 15 per cent of project cost up to Rs 30 lakh, plus subsidy in case of timely repayment”—explains the scheme’s popularity. “A bouquet of schemes for NRKs is in the pipeline. Whether these are rolled out is predicated on whether the Centre allows us to borrow the funds we need,” says R. Ramakumar, a Kerala planning board member and economics professor at TISS. The finance minister was less circumspect. “All the schemes we were planning for the diaspora will be delayed,” Isaac says.

Benoy Peter, executive director of the Perumbavoor-based Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development, has a different kind of ambition. He sees returnees as carrying skill-sets honed in hyper-global locales. “A registry of skills needs to be created,” he says. That will facilitate optimal deployment, as also reskilling/upskilling to improve remigration prospects—he sees Africa as the next frontier. With public funds scarce, it may work best if those who are able to do so invest creatively in the future. Rajan of CDS suggests the state must attract NRK investments towards social schemes, shares and other financial instruments. “They invest heavily in such traditionally prized, but non-performing, assets like land and gold. To shift this pattern, the trust deficit would need to be overcome,” he notes.

To that end, some contend, NRKs need a political voice. In February, the statutory Kerala NRI Commission formally sought an amendment to the Representation of the People Act to enable NRIs to vote by proxy. “It is not frivolous and deserves to be heard by the Union law ministry,” says Justice (retd) P. Bhavadasan, the body’s founding chairperson. The 600-odd petitions he has heard have given him a bird’s eye view of a festering social canker. “Most NRKs don’t have savings. Roughly 65-70 per cent of their life’s earnings are remitted to their families; about 10-15 per cent goes towards living expenses in their host country. They spend under 10 per cent on themselves,” he says. That’s why, he says, “less than a quarter of the returnees can be said to have integrated fully into society”. Over 25,000 returnees are “on the street,” he says. The Dubai-based Pravasi Bandhu Welfare Trust too had found that 95 per cent of NRIs across the GCC return home with next to no savings. The stigma of failure means they rarely report it too. For every Yussuf Ali, there are thousands of cautionary tales.

Shihab*, a returnee from Saudi Arabia, was determined not to become one. He spent 30 years setting up a chain of Kerala-style thattukadas (dhabas), putting his children through college and slowly creating a nest-egg before taking a golden parachute so as to spare his old arbab (boss) the vagaries of the Kingdom’s colour-coded nitaqat regime. It was no mid-life crisis then that spurred him to buy a 4BHK on the Kochi backwaters. “It was a retirement investment for my wife and me. It was our little slice of paradise.” Shortly before noon on January 11, paradise was lost as carefully placed emulsion explosives tore down the two residential blocks of Alfa Serene—aptly named the ‘Twin Towers’. “Our world came crashing down,” says Shihab, who still feels the sting of the clapping, hooting, hollering, breathless TV circus. For most NRK owners of the downed towers in Maradu, found to be in violation of CRZ norms, the experience was Kafkaesque. The only silver lining the COVID lockdown afforded them was that it put a stop to the voyeurs indulging in ‘debris tourism’ around the desiccated husks of the flats. How may one label that site? A memorial to hubris? A graveyard of dreams? Or an art installation for the next Kochi-Muziris Biennale?

(*denotes name change)

By Siddharth Premkumar in Thiruvananthapuram