Gandhi arrived in South Africa in 1893 to fight a case for an Indian merchant, but stayed on when his services as a London-educated barrister were required by the fast-growing Indian community to combat the Natal legislature’s Franchise Amendment Bill—a racist law that aimed to withdraw voting rights from Indians—fearful that a fast proliferating people would soon outvote the ruling Whites.

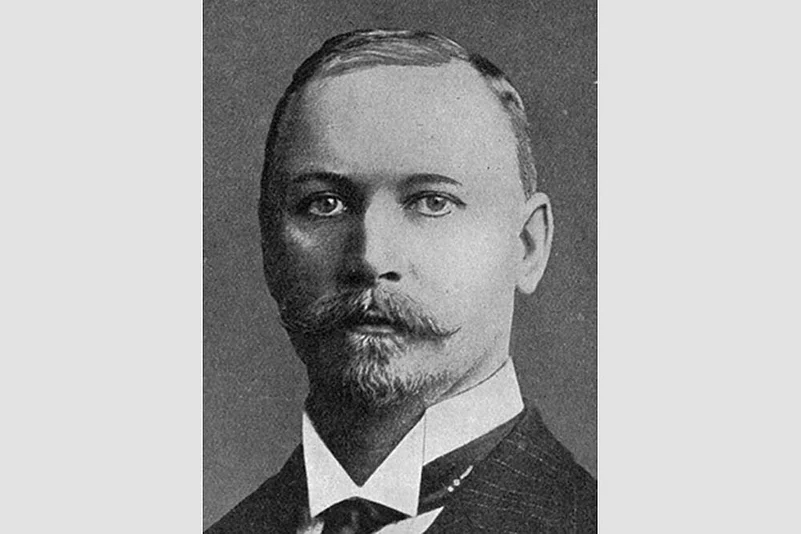

In this Natal was united with the racist Boers in inland Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Gen J.C. Smuts was appointed colonial secretary of the Transvaal in 1907, as post Boer War reconciliation between the British and ‘natives’ of Dutch ancestry thickened.

Well-educated and cosmopolitan, he was, however, as racist as others on the grant of equal franchise to ‘coolies’, the entry of Asians into the Transvaal and the steep £3-tax that indentured Indians had to pay when their contract expired. Gandhi first met Smuts in April 1907 to appeal against the compulsory registration of Asians, involving fingerprinting, under the Asiatic Act.

Gandhi offered a compromise in lieu of withdrawing the Act. He was rebuffed. A policy of passive resistance was fashioned. In December 1907, he and 22 others were arrested for resisting registration. It was now that this was called ‘Satyagraha’. A compromise was sought, and Gandhi and Smuts met again in January 1908. Smuts promised to repeal the law.

Yet it was apparent that he had gone back on his word, even as hundreds registered. Gandhi felt betrayed. The two men met thrice in three weeks in June 1908, where Smuts denied making any promise. Satyagraha resumed—scores courted arrest by plying their trades without permits, many burned their registration certificates.

In Gandhi’s next meeting with the general, the government backtracked, allowing ‘pre-war residents’ to return and register, exempting those below 16, though blocking ‘educated Indians’—a perceived threat to Boers. The Asiatic Act won’t be repealed; nor would it be activated. Soon after, Smuts expressed helplessness in the teeth of non-violent Satyagraha.

The Asiatic Registration Amendment Bill, too, did not placate Indians, who resorted to mass agitation. In January 1911, a new Immigration Bill was vague on the status of the wives and children of Indians (later it was clearer—non-Christian marriages were invalid). Now, the Orange Free State objected to Indians’ entry. Gandhi met Smuts in March and April 1911, with the latter asking for time.

But the draft Immigration Bill passed in May did nothing to alleviate the principal sore points—the £3 tax, the racial bar in Free State and the marriage question. Gandhi called for Satyagraha again—his single largest action, presaging his great movements in the ’20s and ’30s. In addition, hundreds of miners struck work, including 15,000 sugar workers; thousands went on strike.

In November 1913, Gandhi led a march to the Transvaal. He was arrested thrice in four days. Gandhi again met Smuts, promises were extracted, new work on the Bill started. Finally, Indians’ Relief Bill was passed in June 1914. It accepted the main demands of Indians.

Victory won, Gandhi left South Africa. Smuts was glad to see his back. Gandhi sent him a pair of sandals he had made in prison as a farewell gift. Years later, Smuts wrote to him: “I have worn these for many a summer, even though I may feel that I am not worthy to stand in the shoes of so great a man.”