A stark fact. It’s the world’s largest democracy, one-fifth of the planet’s population. And one-fifth of that—India’s largest minority, the Muslims—have never had a collective political platform that directly represents them in independent India. The fact relates, in a way, to the very fitness of Indian democracy. The burden of ensuring their well-being has always been outsourced to ‘secular’ parties (who have borne it with very indifferent success). Why? Because the idea of Muslim political representation has a risky, dangerous past. After all, the fear of under-representation is what bought support for the Muslim League, eventually leading to Partition and its infinite madness. Any loud, visible Muslim assertion thus stokes those subterranean fears. Its bequest: a stark political vacuum.

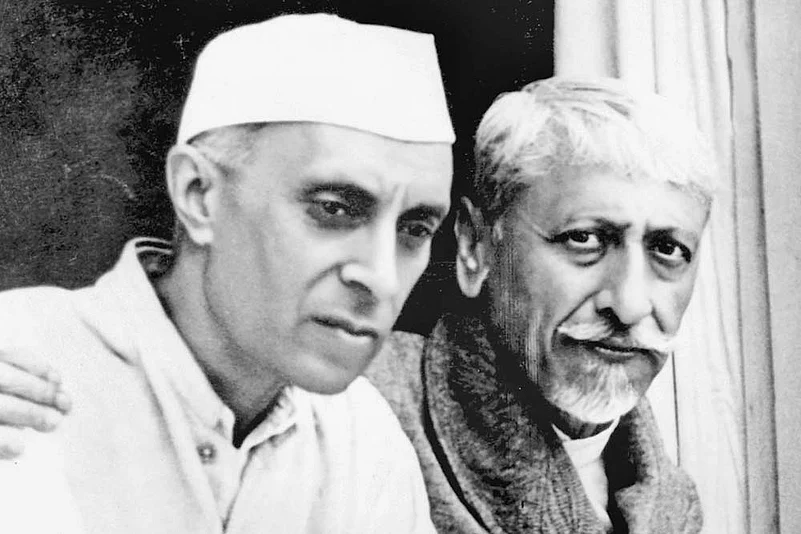

And so, the first towering Muslim leader with a pan-India acceptance across communities—Maulana Abul Kalam Azad—is perhaps also the last one who answers to that description. The erudite Azad, India’s first education minister, leaves behind a template that’s almost inconceivable now. And invites the question. Can’t a Muslim leader be not just ‘only for Muslims’?

A potential answer to that comes from the streets. Look at the ongoing anti-CAA agitations. They possess one striking facet: they are leaderless. There is no group or political party or leader who or that is, or claims to be, the one propelling them. At one level, that frames the political orphanhood of Muslims. But also, very saliently, the agitation is turning a whole battery of notions on their head. Yes, it’s an agitation that has the Muslim community at its centre—a natural consequence of how the CAA/NRC process is seen to leave them singularly and most vulnerable. But it’s also a general agitation—on constitutional points, with the Preamble, the national anthem and the tricolour on full display. Very strikingly, Muslims are leading a political movement from the front, from a space of belonging, and everyone else who believes in those ideals is joining in!

In his famous speech of 1947, Azad exhorted Muslims to stay back and embrace the country as their own. “Where are you going? And why are you going? Look here, the minarets of Jama Masjid ask you something. Where have you lost the pages of your history? It was only yesterday that your caravans performed ablutions on the banks of Yamuna here. And you are scared of living here now? Remember, Delhi has been nurtured with your blood.... Come, let us pledge today that this country is ours. We are meant to be here and without our voice, the fundamental decisions of this country’s destiny will remain incomplete.” In a crucial way, Shaheen Bagh answers that call.

But what happens from here on, in the absence of a credible, strong Muslim political presence that could echo and amplify the aspirations of the community? Does that leave them without sufficient political agency? The number of Muslim MPs in the Lok Sabha has varied between 21 (1952) and 49 (1980), with the figure parked at 27 at the moment. The CAA moment may come and go, the question of representation will remain alive and vigorously contested.

At one level, so entrenched is the idea that ‘Muslims caused Partition’, it debars any reckoning with the paradoxes of that history. That Hindutva ideologue V.D. Savarkar propounded the two-nation theory 16 years before the Muslim League. Or that, while a London-educated, ritually-scant, ambitious barrister helmed the demand for a separate Muslim state, the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind (JUH), a body of theologians rooted in the Deobandi school, opposed it tooth and nail.

And so, aside from a handful of chief ministers and Union ministers, and token Presidents, the slate is still empty. And anyone in the mould of Badruddin Ajmal in Assam, not to speak of Asaduddin Owaisi, still evokes the old fears—sometimes struggling against it, sometimes using it. But what about the Azad template? Rizwan Qaiser, professor of history at Jamia Millia Islamia and Azad’s biographer, says the leader gave great stability to Muslim concerns in the initial years. “But during the 1940s, he started losing out to the Muslim League. Many considered him a renegade, but post-Independence they realised there was no other voice left for Muslims,” says Qaiser. And Muslim anxieties, immense in those years after Partition, came to be allayed by Nehru’s unwavering commitment to secularism. The Left too offered similar refuge in later years. The power of attorney phase was truly on.

ALSO READ: Why No Shaheen Bagh In Kashmir?

Azad died in 1958 and for the next few decades there was no Muslim leader of prominence on the national landscape. There was a reason for that, Qaiser argues. The concerns of Indian Muslims, by no means a monolithic community, diversified after Independence and that made the idea of a pan-India Muslim leader a difficult proposition, he says. And so it was that the vacuum in the decades after Azad was often filled by bodies of clerics like JUH or outfits such as the All India Muslim Personal Law Board or the All India Muslim Majlis-e-Mushawarat.

The lone figure who cropped up in that phase—Syed Shahabuddin—did nothing to alter the stereotypes or the discourse, or earn wider endorsement. An erudite foreign service man who was thrice elected to Parliament, his starring role came in opposing the court judgment in the Shah Bano case and calling for a ban on Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. By the time of the Babri Masjid episode, his bargaining power vis-a-vis the State had already been marred by the image of a hardline man. “No doubt he was a bright man and one of great scholarship. But his politics was retrograde and divisive. He saw Indian society only through the prism of clergy and elites,” says Shajahan Madampat, a keen commentator on Indian politics and culture.

(From L to R) Asaduddin Owaisi of AIMIM, Badruddin Ajmal of AIUDF and Azam Khan of Samajwadi Party.

The next phase, marked by the BJP’s arrival on centrestage—and a new precarity in Muslim lives—also saw the emergence of parties premised on ideas of social justice, who now took ownership of the secular guardianship mantle. Parties such as the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Rashtriya Janata Dal also opened up some limited avenues for Muslim leaders to come up (though never all the way to the top).

One such leader offers an interesting case-study, for the gap between what he communicates to the wider public and to his constituency, and for his own feelings about the ‘Muslim question’. Azam Khan of the SP, known to television audiences more for his intemperate and casual sexism, is also a man whose occasional presence in government reassures the Muslims of Uttar Pradesh. He also buys credence for the SP among them, while calling himself a secular leader and never much doing overtly religion-based politics. At present enduring a witch-hunt by the state’s BJP government (with over a hundred cases, ranging from book theft to land grab), the nine-time MLA contested a Lok Sabha election for the first time in 2019 and won.

Days before that, in an interview to Outlook, he had put forth an astonishing proposition: “I suggest the voting rights of Muslims must be revoked and the right to study, right to earn livelihood and right to exist be ensured to them. It’s when a Muslim goes to vote that the fascists take objection. If Muslims don’t have a vote, there will be no resentment,” he had said. What more dire sign of the community’s political attrition than the idea that they forfiet their franchise itself! Congressman Ghulam Nabi Azad’s lament that he was not being called for campaign by candidates, and former Rajya Sabha MP Mohammad Adeeb’s suggestion that Muslims withdraw electorally for some time, all attest to the same straitening of space. The political air, in fact, made all parties keep Muslims at an arm’s length.

Ahead of the 2019 polls, Azam Khan had also made an impassioned speech with words strikingly similar to Azad’s in 1947. “No matter what anybody calls you, know that the country’s picture is incomplete without you. The borders were open in 1947; we could have gone, but we didn’t. Because this is our country. This land is ours. This sky is ours. Ashfaqullah Khan’s sacrifices, Delhi’s Jama Masjid, Qutub Minar’s majesty, Taj Mahal’s beauty, Ambedkar’s Constitution, the holy book that teaches you how to live, swear on them, swear on your ancestors, this country is yours,” Khan had told a riveted crowd in Rampur. That the rhetoric has changed little in 70 years speaks copiously about the continued precarity of Muslims.

Within the Congress, faces such as Salman Khurshid, Ahmed Patel or Ghulam Nabi Azad have little appeal among the Muslim populace, and they themselves have rarely tried to address the concerns of Muslims forthrightly. Zoya Hasan, professor emerita of political science at Jawaharlal Nehru University, says the Congress accommodated minorities through cultural recognition, but was reluctant to provide affirmative action or proportional representation to minorities. “The rise of the BJP, on the other hand, has seen a shrinking of political representation and agency of Muslims as it has more or less declared that there can be no political or cultural representation of Muslims under a majoritarian dispensation,” says Hasan.

It’s in this economy of scarcity that an Owaisi comes as a very striking, potent presence—sharp, ardent, articulate, legally erudite, demonstratively Muslim, a kind of new claimant to the ‘sole spokesman’ slot in the Indian context who punches way above the weight category demarcated by his small Hyderabad-based party with single-digit MPs and a dozen-odd MLAs. The way he speaks consistently and combatively on issues that concern Muslims all over, indeed the way he calibrates his voice even to general national themes—once, in 2013, even offering the most eloquent defence of the Indian system on a Pakistani debate platform—gives him way more potential than, say, Ajmal of Assam (who is richer in purely electoral terms).

To wit, Owaisi is now making inroads into states such as Bihar and Maharashtra, and his national ambitions are writ all over his politics. The accusation that he eats into the voteshare of secular parties, in a way helping the BJP, lingers. He has ready answers, though, and responds by saying he wants one MLA in every assembly who can seek accountability from secular parties (as he told The Print once). “His gaze is pan-Indian,” says Adnan Farooqui, who teaches political science at Jamia, “and his felicity with language, teamed with his understanding of issues, set him apart. In fact, he understands media better than many leaders, let alone Muslim leaders.”

But Owaisi has a problem. Foremost, he hasn’t disowned, apologised for or condemned a rabid hate speech of his brother Akbaruddin Owaisi. Also, as Madampat puts it, what he does is more of identity politics than communitarian politics. “Identity politics is always about emotive issues of religion, caste, language…communitarian politics focuses on material development and real-life issues of the community,” says Madampat, who confesses his admiration for Owaisi’s speeches in Parliament, but violently disagrees with the tone and tenor of his speeches in election rallies. This is perhaps what alienates other communities and holds him from leading a broader social group of underprivileged sections, as per the stated vision of his party. Whether he intends to is debatable.

An interesting point of comparison is the Indian Union Muslim League of Kerala, which had, albeit for less than two months, even a Muslim chief minister in 1979. The party, Madampat argues, has shown strands of identity politics, but largely remained communitarian; it has at times been conservative, but never communal. It has furthered Muslim aspirations without antagonising any other segment—and hence has retained its centrality in the larger Kerala polity. “This is why Muslims in Kerala feel a greater sense of equal citizenship, as opposed to their counterparts in other states,” he argues, “while not discounting other factors such as the state’s deeper social harmony. In the face of secular, umbrella parties failing to sate the aspirations of communities, communitarian politics might be the way forward for Muslims in the rest of India.”

But can this succeed in north India? Pockmarked as it is with a history of riots, lynching, cow vigilantism and the deep faultlines laid by the Ayodhya movement? The deeply polarising rhetoric ahead of the Delhi assembly elections might offer a clue. The most recent example is of BJP MP Giriraj Singh, who said Pakistan was created for people like Owaisi (very ironic, given that 2013 speech in Pakistan, which may have been safely beyond the voluble Singh’s league). References to Pakistan abound in BJP campaign speeches, of course. UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath, in the run-up to the Telangana assembly elections in 2018, had said if the BJP came to power, Owaisi would have to flee just the way Nizam did.

Owaisi, an archetype of Muslim assertion, is erected as the enemy time and again by the BJP to ignite the dormant fears of the majority, in a way telling them, ‘See, they are rearing their head again.’ But with the magnitude of churning at present, with a language more open and creative than Owaisi’s, perhaps the old fears will metamorphose into something else. The reign of token secularisms and ahistorical ideologies with their out-and-out absence of nuance have had their run. The streets now brim with an air of expectancy.