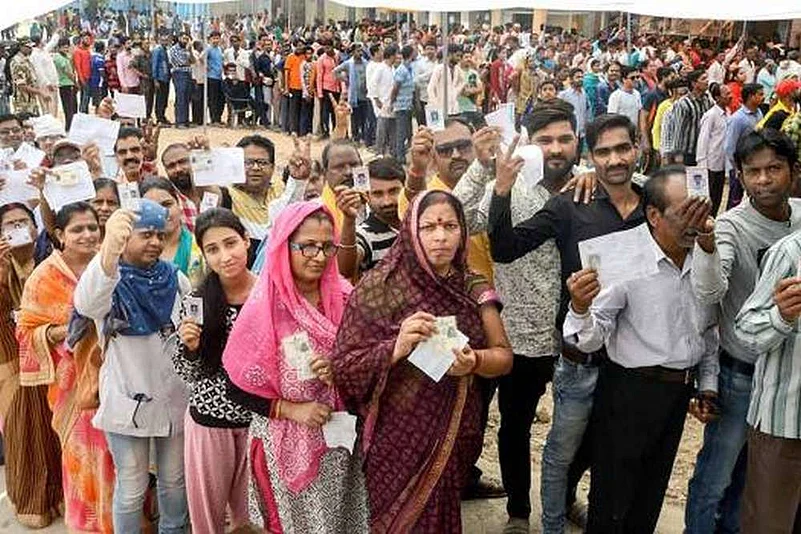

Between the 1980s and the first decade of this century, the Indian middle class was apathetic towards elections. But in the 2014 general election, it turned out in huge numbers to support Narendra Modi. The story was the same in many of the recent assembly elections. The low turnouts in the first three phases of the ongoing national election, however, indicate that the middle class has once again opted to stay at home, rather than go out and vote.

What explains this paradoxical attitude of the burgeoning middle class towards politics and elections? The short answer is economic self-interest. The long answer is complex. Before we delve into the trends that defined such electoral oscillations, it is apt to clarify that the middle class isn’t homogeneous, but is as divided according to class, caste, creed, socio-economic status and religion, as the rest of the society. Hence, the issues that we describe may have impacted the various sub-sections in different ways.

Four trends shaped the politics of the middle class over the past four decades. These include reforms and job opportunities, a drastic reduction in central subsidies, Demographic Dividend, and socio-economic activism. Together, they impacted the class, which went through phases of prosperity, frustration, and anger. These changing emotions forced it to either walk away from politics or join it with enthusiasm and excitement.

Although the Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh duo is credited with reforms, they began in the 1980s when the late Rajiv Gandhi initiated policies like import liberalisation, computerisation, and the foreign joint ventures. Since 1984, the jobs market opened up, and expanded after 1991. In IT, telecom, financial services, retail, and infrastructure, there was an employment boom. The middle class believed that it could thrive despite the government.

At the same time, the government, as the largest job creator, lost its appeal as it downsized. For the middle class, the private sector or self-employment became the means to achieve financial well-being. It thought that it didn’t need to engage with the corrupt and inefficient governments since the latter could not turn the clock back and re-introduce the old Licence-Quota Raj.

Sadly, the financial party ended in the 2000s, as India entered an era of jobless growth (2004-14), followed by a worse period of lower employment (2014-19). According to a leaked draft NSSO report, the unemployment rate was the highest in four decades in 2017-18. The middle class faced a new crisis due to a huge reduction in central subsidies (food, fuel, fertiliser and others), as the governments struggled to manage their finances. The subsidies, which largely benefitted the elite classes, were now targeted at the poor.

A frustrated class seemed unable to do anything about its interests. It realised that the only way out was to force the governments to dole out new benefits. This became imperative when the financial and tax doles that it got lost their relevance as the policy makers decided to expand the tax base and impose taxes on services that harmed the interests of the self-employed. (Today, the taxes are included in the single Goods and Services Tax). However, the middle class felt that it didn’t have the political clout to do so.

At this stage the Demographic Dividend factor kicked in. Large sections of the middle class, especially the youth, realised that they had the numbers to make electoral differences. Recent media reports stated that “81 million young voters will vote for the first time in the 2019 national election and can decisively influence electoral outcomes in 282 parliamentary constituencies”. Such numbers gave the confidence to the middle class that it can force regime changes.

Parallel to the above processes was the fact that despite its electoral lethargy, boredom and indifference, the middle class flirted with several indirect political decisions. This was the result of its links with social, economic and environment activism. In 1989, it agitated against job quotas and Mandal Commission, protested against big dams and deforestation in the 1990s, and dissented against corruption in the 2000s. These instilled an underlying belief that it could both hope and push for changes.

The combination of frustration, anger, confidence and faith forced the middle class to come out in large numbers for the various elections. It voted Modi to power in 2014, supported Akhilesh Yadav in the 2012 Uttar Pradesh assembly polls, enabled the late J. Jayalalithaa’s victory in Tamil Nadu (2016), and helped Kejriwal to grab 67 out of the 70 seats in Delhi (2015). Alas, the political party ended with huge disappointments. The promises of growth, jobs, development, and new subsidies remained unfulfilled.

(The author is a Delhi-based journalist.)