Three months after it first mapped out the country’s COVID-19 footprint, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) finally published the details of its survey in early September, by which time the information had become outdated. Still, it did provide a clearer picture of what the early stage of the epidemic in India looked like. First, that there likely were 6.4 million infections by early May when the month-long nationwide serosurvey was carried out—the study involved 28,000 individuals across 70 districts and the results indicated that 0.73 per cent of India’s adult population had been exposed to the virus. It meant that for every Covid-positive case confirmed by a swab test, there were 82-130 infections that hadn’t been picked up.

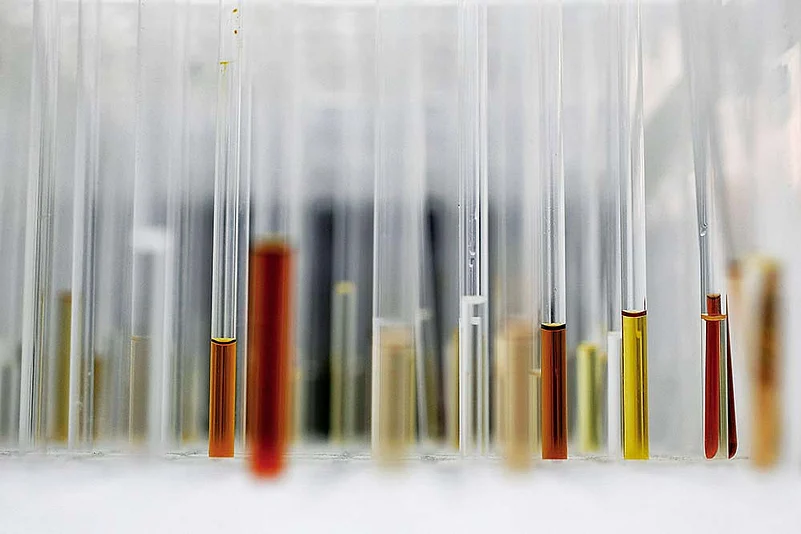

Experts reckon that’s not unusual—these are antibody tests that scan blood samples for Immunoglobulin G (IgG), which the body produces to fight an infection. After all, the RTPCR swab test is largely conducted on people with symptoms (and those who report them), so its net isn’t wide enough to catch all infected people, given the high number of asymptomatics.

ALSO READ: Billion-Dose Race

Seroprevalence surveys, as epidemiologist Jayaprakash Muliyil explains, illustrate the iceberg phenomenon. “The daily tallies of Covid cases and recoveries are only the tip of it,” he says. “The serosurveys give you the view of the remaining iceberg.”

In the three months that ICMR laboured over its results—by now, the council is well into its second national survey—there have been other independent serosurveys in the big cities. Delhi’s first survey (conducted late June-early July) came up with the finding that 22.6 per cent of the city’s population had been exposed to the infection. In its second round a month later, that figure rose to 29 per cent (this week, the September survey results are expected to be announced). Around the same time, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai did a random sampling of three wards and came up with an estimate of 57 per cent seroprevalence in slums and 16 per cent in non-slum areas.

Meanwhile, in Pune, a study of five prabhags, or sub-wards, with high incidence rates found 51.5 per cent seroprevalence in the localities sampled—the prevalence rates ranged from 36.1 to 65.4 per cent in these five sub-wards. The study also reported that hutments and tenements appeared to have higher seroprevalence than apartments and bungalows. In early September, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation said that its second serosurvey—involving 10,310 samples—indicated a 23.4 per cent seroprevalence, about five percentage points higher than the previous round. The same week, authorities in Chennai announced the findings of a serosurvey that suggested a fifth of the city’s population had been exposed to the infection.

The methodologies adopted varied—for instance, Delhi claimed its sample was representative of the city, while the Mumbai and Pune survey had narrowed in on a few wards. What insights do these studies provide? “They may give some idea of what threshold might have been reached within a population. But it doesn’t give you any gilt-edged guarantee of herd immunity,” says Prof K. Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India. The serosurveys too carry that disclaimer because it is unclear what level of prevalence would lead to herd immunity.

Reddy also points to other limitations—like sensitivity of the tests—that need to be factored in. “Just like the viral tests are likely to yield a deflated number, antibody surveys could also pick up false positives and thereby show inflated numbers,” he says. “But the fact is, with all this noise in the signal, you still get some idea if you are repeating it in the same population.”

“One serosurvey will never give much information. We need to repeat it to know where we are heading,” says epidemiologist Giridhara R. Babu, who was associated with ICMR’s national survey. Given the time span of a few months between the two rounds, the ongoing second national survey is bound to reflect a big change in readings, he reckons.

Aurnab Ghose of the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune, who collaborated on the Pune serosurvey, says efforts to tease out more information from their study samples is ongoing. “They have antibodies, but it doesn’t necessarily mean these are protective antibodies, or neutralising antibodies. We are now trying to see, from the samples that we collected, if we can get a sense of the neutralising activity,” he says. “There have to be subsequent serosurveys and now all these cities at least might want to think of what are called longitudinal studies, which is to sample either the same population or even the same people over a period of time.”

Herd immunity, as a ‘fire escape route’ from the epidemic, is still a long way off, says Reddy. “Firstly, we don’t know what the herd immunity threshold is.” The term itself refers to the phenomenon of an epidemic dying out when the virus is unable to reach new hosts owing to the large population of infected people (who are, therefore, immune) blocking its circulation. Even assuming one locality in a city reached that stage, it would mean that an uninfected individual is safe only so long as he stays within that protective cordon, says Reddy. “The moment you step out of that immune zone and go to some other zone where the virus is active, then you are still vulnerable.”

Muliyil, who is chairman of the Scientific Advisory Committee of the National Institute of Epidemiology, believes that the herd immunity threshold may actually be lower than previously assumed. “The herd immunity requirement is a function of population density,” he tells Outlook. It could be a little less than 60 per cent in a densely populated slum like Dharavi and thereby even lower in rural areas, he estimates. The early ICMR serosurvey in Dharavi, he says, showed about 36 per cent seroprevalence. “And in a couple of weeks’ time, we noticed that the Dharavi (positive case) numbers were coming down. So, something was happening there, right?” Muliyil points to the containment zones in many cities that have since recovered. “I think what is going on is that many of the containment areas where poorer people were living, they were hit first. Now, it is moving into middle class and upper sections.”

The early ICMR survey indicated that the majority of the Indian population is still susceptible to Covid. “You have to make sure that you retain your protection measures for quite some time to come—physical distancing, masks and particularly preventing super-spreader events of large crowds. Those are going to be absolutely critical and we cannot afford to be careless,” says Reddy.