Who gets it first? When is my turn?

The Indian goal is to vaccinate around 30 crore by September 2021. Four categories of priority beneficiaries have been identified for initial phase of inoculation:

1 crore healthcare and frontline workers, including MBBS students and ASHA workers

2 crore municipal workers, police and military personnel

26 crore people above 50 years of age

1 crore people with comorbidities such as high BP, diabetes and heart condition

***

This is the year of the scourge. Of the mystery virus. Of the plague that has convulsed the world and brought humanity to its knees in one single sweep of its tentacles—put millions out of work, devastated economies and forced many to undertake perilous road trips on foot across hundreds of kilometres. 2020 has truly been, as the Queen Mother once memorably said, an annus horribilis. And not since the HIV pandemic hit our tiny blue planet in the ’80s has the world looked so desperately for a cure to this ailment that has killed more than 1.2 million people globally.

Yet, hope springs eternal. And the collective dream of humanity is that 2021 will be the year of the vaccine—the panacea, the universal injectable remedy that would bring our lives back to order, booster-dose economies and put the word quarantine back into the dictionary. But the bigger question is: when will a vaccine be available for the public? There is no clarity on this yet, even as government agencies and private companies across the world race against time to find a workable antidote against COVID-19.

ALSO READ: Delivery Awaited

Let us look at it shot by shot. The sprinters first off the starting blocks in the global race that began late January are nearly at the finish line—the efficacy and safety data from some of the keenly watched trials such as University of Oxford and Pfizer are due anytime now so that regulators can begin their review. For an emergency-use case, that is. The World Health Organization (WHO) says more than 200 vaccines are under different stages of trials—nearly 50 are undergoing human testing. If one or more candidates pass muster, a whole new task presents itself—a gigantic vaccination drive on a scale the world has not seen before. Look only at the target of COVAX, the global alliance for equitable distribution: two billion doses of a safe and effective vaccine by the end of 2021. And, that is a response to the rush for independent pre-orders from various countries—one estimate by the US-based Duke Global Health Innovation Center claims 8.8 billion doses have already been reserved.

For India, the challenges are even more staggering. That eventual rollout can be mind-boggling—call to mind India’s Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP), which every year targets roughly 26 million newborns through nine million sessions a year. It is among the world’s largest. For a Covid vaccine, however, multiply that target group several times over—estimates of the number of people likely to be prioritised to receive a vaccine run into 300 million. “We have the experience of implementing large-scale immunisation campaigns,” Union health minister Harsh Vardhan tells Outlook. “We are further augmenting this system to ensure that the massive national mission of vaccinating the identified priority groups with Covid vaccine is achieved in a timely manner.” (See Interview)

Four decades after the virus was identified, scientists are still looking for a vaccine.

Numbers Game

But a task of this scale and nature has not been attempted before. According to rough estimates, the first vaccine could be ready by the first half of 2021. And since only those with immediate need will be given first preference, it could take another year or two for others to get the vaccine. And how many will need the vaccine as soon as it is available is also a matter of data projection—at present, India has at least 5.3 lakh active cases, though the countrywide positivity rate is said to be falling. For the record, India’s Covid death number (1.2 lakh out of 8.3 million cases) is the third highest in the world after the US and Brazil. Virologist Shahid Jameel says that to inoculate about 60 per cent of India’s 1.38 billion people—the supposed threshold for herd immunity—the country will have to vaccinate 828 million people. And considering all sources of the vaccine, the projected rate of production, and logistics of delivering the vaccine to the target group, it could take nine years to achieve this 60 per cent coverage (See ‘Known Unknowns’).

ALSO READ: Against Vaccine Nationalism

“This is a very, very big logistic, administrative, political exercise...political only because it will be seen as political,” says former health secretary Keshav Desiraju. “Every detail,” he points out, “feeds into the other.” Politics will indeed play a big part with several states already announcing plans to provide the vaccine for free. How it will be done is a matter of conjecture. At the moment, there are a host of imponderables.

The operational details of who will get a vaccine first, according to Dr V.K. Paul, Niti Aayog member who heads the National Expert Group on Vaccine Administration for COVID-19, are yet to be formalised “because it will depend on how many dosages are available at that time”. Clearly, there is yet some way to go. Adar Poonawalla, CEO of vaccine manufacturer Serum Institute of India, reckons the Indian trials of the Oxford vaccine will be completed by January, possibly the earliest indication from an Indian point of view because the other contender—developed by Bharat Biotech—is recruiting volunteers for Phase 3 trials this month. “The situation is dynamic, about the pandemic and availability of vaccine,” Paul tells Outlook. “We will respond to the emerging situation in the most rational way.”

Those caveats escort every possible scenario. For instance, Britain has struck agreements involving six leading candidates to buy 350 million doses, and the buzz there last week was about the first emergency doses coming in by Christmas. “However, we do not know that we will ever have a vaccine at all. It is important to guard against complacency and over-optimism,” wrote Kate Bingham, head of the UK’s Vaccine Taskforce in The Lancet. Complacency because the coronavirus is raging again in Europe after a lull and partial lockdowns have returned there. “The first generation of vaccines,” Bingham said, “is likely to be imperfect, and we should be prepared that they might not prevent infection, but rather reduce symptoms, and, even then, might not work for everyone or for long.” The US Food and Drug Administration guidelines—as does India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation—expect a Covid vaccine to prevent the disease or decrease its severity in at least 50 per cent of people who are vaccinated.

K. Sujatha Rao, former Union health secretary, points out that in 2010, at the early stages of the H1N1 outbreak, the vaccine had a poor response because it had a 50 per cent efficacy, resulting in a large number of vaccines lying unused. “I will like that the vaccine is at least 70 per cent effective so that the (disease) transmission stops,” says Prof N.K. Ganguly, former chief of the Indian Council of Medical Research who drafted India’s Vaccine Policy in 2011. Given that no data has yet come in from any of the late-stage clinical trials, Ganguly reckons the earliest date for actual deployment could be the end of March 2021.

Meanwhile, glimpses of the ingredients that will go into this giant operation are emerging. India’s current capacity for syringes, for instance, is about 720 million pieces per annum and manufacturers hope to ramp up to 800 million pieces by January, says Rajiv Nath, forum coordinator of Association of Indian Medical Device Industry and managing director, Hindustan Syringes & Medical Devices Ltd. These expectations are based on a recent Indian government order for 52.4 million syringes for Covid vaccines. Another order, likely in the region of 94.5 million pieces, is expected by March, says Nath. “Industry expectations are of the Covid vaccines being available by December-end or January. The government is accordingly gearing up for the rollout,” he says.

Target Group

Before that, some key questions need to be sorted out: how do we prioritise? Do people who have recovered from Covid require a shot? Or simply, what goals do we want to achieve with a vaccine? “If eradication is the goal,” notes virologist T. Jacob John who pioneered the pulse polio campaign, “we need to identify susceptible people and vaccinate them in a short period of time.” India has immense experience from the polio eradication days, but obviously a different tactic has to be worked out, he says.

ALSO READ: Puppetry Of The EVM Vaccine

V. K. Paul says that the government is working out how it should be done and defined the principles. These, he adds, are broadly aligned to those enunciated by WHO and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). If supply is limited, the CDC has set four goals for deciding who to recommend for a vaccine—“decrease death and serious disease as much as possible; preserve functioning of society; reduce the extra burden the disease is having on people already facing disparities and increase the chance for everyone to enjoy health and well-being.” So far, the central government has asked states to create databases on health workers—all workers, medical or non-medical, from government or private health facilities are a priority group followed by frontline workers of other departments.

Most experts note that India has limited experience with vaccinating adults. For instance, flu shots for adults have not had much uptake here unlike in the West where it is the No. 1 vaccine, points out Bijnor-based paediatrician Vipin Vashishtha. The measles-rubella (MR) campaign in 2017 took the existing immunisation platform a notch higher when it went to schools to immunise children up to age 15. That experience, experts say, holds out a lesson on building trust, given the initial hesitancy and fears fuelled by misinformation which the MR campaign faced. But tackling scepticism calls for more transparency, says Amar Jesani, editor of the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. “People will volunteer if there is trust created where you are informing them about how the trials are going on, who is going to get it and why,” says Jesani. “When you go to the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI), you will find it doesn’t provide you clear information on that.” Only about four companies globally have made their trial protocols public, he points out. The other key element: equitable distribution. “A lot of communication and advocation will have to be handled,” notes Ganguly.

Head-start

Dr Mahnoor Kadri normally starts her day by calling up healthcare workers about entries into the electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network (eVIN) app. Then she checks the cold-chain points (CCPs) on a dashboard, looking for the ones that are about to go out of stock or are not updating their current situation. Kadri is the District Vaccine & Cold Chain Manager at Srinagar, a cog in the massive apparatus that currently keeps India’s Universal Immunisation Programme going. “In a fraction of a click, I am able to see the UIP vaccine status of entire Srinagar and pinpoint the smallest loopholes.” On Wednesdays and Saturdays, the designated days for immunisation, she is out on field visits to the cold chain points. The eVIN, set-up in 2015, has streamlined the vaccine supply-chain, she says. “Now there is accountability for every single vial that is being given to any facility, which was not possible earlier.”

A COVID-19 vaccine rollout will plug into this same system. Here is where another set of challenges loom—India’s cold chain typically handles vaccines between 2 to 8 degrees Celsius, except for the oral polio vaccine and rotavirus vaccine, which need minus 15 to minus 25 degrees at the walk-in freezers and deep freezers in the depots. Experts say the eventual choice of a vaccine will likely hinge on the cold chain capability because some of the Covid candidates, especially the messenger RNA and the DNA vaccine candidates, will require deep freezing.

“We are factoring in all the scenarios because we do not know which vaccine will be used. Hopefully, the frontrunner vaccines are okay with the normal cold chain,” says Paul. Here, he is talking about the Serum Institute and Bharat Biotech vaccines. “But if we have to depend on other vaccines, we will need a different cold chain system and then we will factor that in. If there would be need to go on a different paradigm, then we will do the needful,” he says.

ALSO READ: Known Unknowns

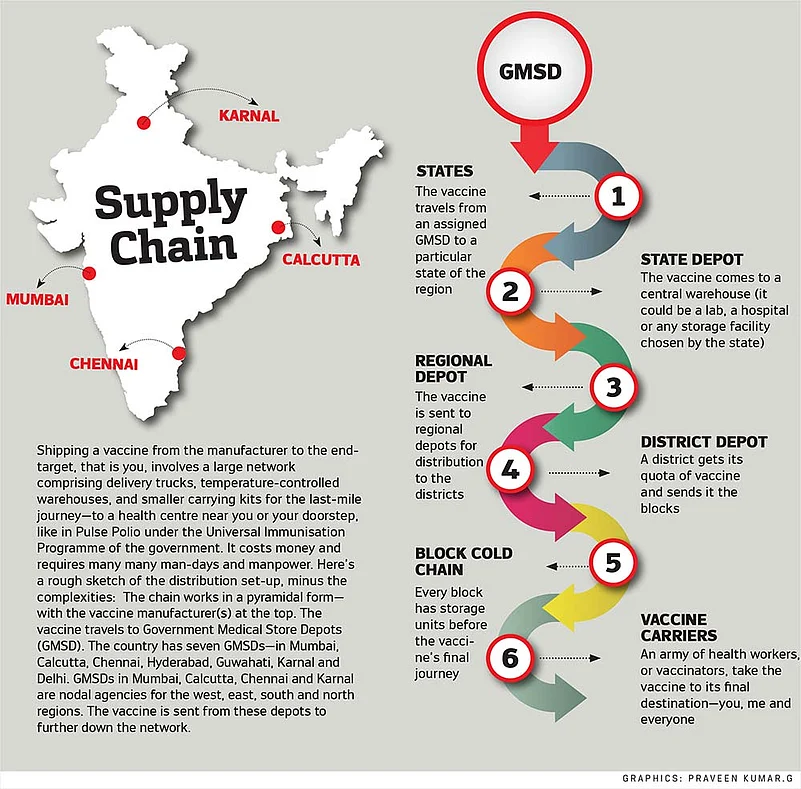

A vaccine’s last-mile journey, even today, is fraught with challenges. Broadly, vaccines go from the factory to four large government depots and then pass through three levels of vaccine stores to states, regions and districts to finally reach the block—the last point on the cold-chain overseen by an immunisation officer (IO). Here, vials are stored in ice-lined refrigerators. An IO from UP’s Muradabad district points out that his post is actually an additional responsibility to his main duty as a community surveillance officer who moves from village to village to gather information about health issues. “The government needs to create a permanent post of IO to roll out the COVID-19 vaccine because the volumes and work will be much more than what it is today,” he points out. Another existing difficulty is that the final leg of the vaccine’s journey—from block to primary health centre—relies on casual daily wage delivery boys. The IOs say they have to persuade youngsters to enlist—for one, it is not a daily job. As one delivery boy in Barabanki puts it, he sometimes cannot drop other odd-jobs he lands in order to deliver vaccine boxes to far-flung villages and bring back the unused vials in the evening. Then, with a Covid vaccine, there will be the added worry of security as well, says an IO. The weak point in our immunisation programme, according to development consultant Geetha Athreya, is in rural India where the auxiliary nurse and midwife (ANM) travels from village to village to administer the vaccines, often on foot. “We need more ANMs as most of the vaccines are intramuscular injections,” says Athreya.

Finally, how much will all this cost the government? There has been no official estimate yet, but two figures are currently in circulation—a Bloomberg news report hinting at Rs 50,000 crore and Poonawalla’s tweet suggesting Rs 80,000 crore. India’s total outlay on health in this year’s budget, for comparison, was Rs 69,000 crore. “In one sense, these figures are not a lot of money for a very major national programme. It is not as though we need that money tomorrow morning. But it is not small money either,” says former bureaucrat Desiraju. Among all the key vaccine imponderables, that is one right up there—how exactly will we be paying for it?

Given all of this, what does a likely timeline for vaccination look like? The earliest for the first doses to arrive, most experts reckon, could be the first quarter of 2021. “Our aim,” says health minister Vardhan, “is to provide the Covid vaccine to 30 crore Indians by August-September 2021. This is a good 22 per cent of our total population.” Even assuming there are enough doses available, it is an onerous task. The measles-rubella campaign, roughly of the same scale, was spread over two years.

For those outside the risk- and age-based criteria, it could be—as reasonable a guess we can make at this point—a couple of years’ wait. How much will it cost the world is, again, a matter of conjecture.

***

Immunisation In India

1802 The smallpox vaccine arrives in India

1897 Plague vaccine developed by Waldemar Haffkine in Bombay, a year after an epidemic broke out in the city

1958 BCG vaccination campaign started in India

1962 National smallpox eradication campaign

1975 Last known smallpox case in India

1978 Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) begins

1985 EPI becomes Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP)

2011 Last case of polio in India

By Ajay Sukumaran, Jyotika Sood and Jeevan Prakash Sharma With inputs from Lola Nayar and Bhavna Vij-Aurora