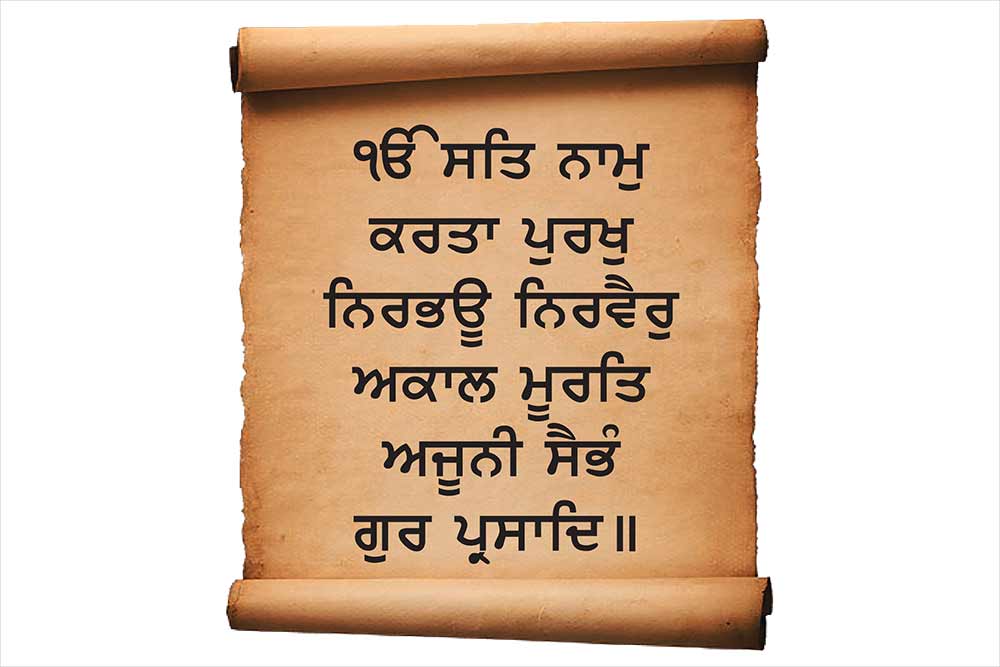

The Sikh model of reality and knowledge, as elaborated in one of its earliest texts, the Japjī Sāhib, makes the ‘word’ or ‘śabad’ (śabda) the fundamental category in its epistemology, ontology and ethics. Japjī Sāhib (composed c. 1505) is the Sikh morning prayer recorded as the Guru Granth Sāhib’s first hymn. Comprising two ślokas and 38 verses, the hymn is preceded by the ‘mūl mantar’ that precedes every rāg or hymn of the Granth Sāhib. It lists seven features of the Sikh deity, setting the agenda for Sikhism’s basic assumptions. The mantar’s first phrase refers to the deity as ‘ik aumkār’, underlining that Sikhism is monotheistic, and that this deity is expressible only as sound, as represented in the aumkār’. The second phrase, which reads as ‘sat nām’, tells us further that the ‘name’ of this deity is ‘truth’ itself. The third phrase, ‘kartā purakh’, makes this linguistic deity the ‘kartā’ (doer), and identifies it with the Sā khya category of purus·a—the primal conscious category. The fourth phrase qualifies this deity as being ‘nirbhau’ (fearless) and ‘nirvair’ (without enemies). The fifth phrase, ‘akāl mūrat ajūnī’, clarifies that the mūrat, or form of this deity, is free of time (akāl), it being not born (ajūnī). The sixth phrase, ‘saibha ’—a Punjabi variation of the Sanskrit ‘swayambhū’—suggests this deity is self-generative. The final phrase, ‘gur prasād’, claims this deity can be known through the guru’s grace—knowledge received from the guru’s words.

The deity’s seven features outline the Sikh system’s epistemology, ontology and ethics. The first, second and seventh features achieve a lingualisation of the deity, whereby it is expressible only through ‘aumkār’, it is a ‘name’ whose primary feature is its truth-value, and it is knowable only through the guru’s words. All this points towards āgama pramān·a or śabda pramān·a —authoritative verbal testimony—as the only valid epistemology in the Sikh way of thought. The third, fifth and sixth features, which talk about the deity being the ‘doer’ and equable with the purus·a, not being subject to time and being self-generative, point towards the Sikh ontology, culminating in the classification of planes of existence into five khan· d·s in the Japjī itself. The second, fourth and seventh features talk about Sikh ethics. The insistence on truth in the second phrase makes truthfulness an important ethical category, while the fourth makes fearlessness and camaraderie the religion’s ethical goals, and the seventh makes obedience to the guru’s authority a supreme virtue.

To gain knowledge, one has to ‘sing ‘ about the lord, said Guru Nanak

That the epistemological status of the ‘word’ is the Japjī’s main concern is clear from its very title—‘jap’ literally means repetitive utterance of words. To establish śabda pramān·a as the only valid epistemology, the text has to first disprove the epistemic claims of the two other pramān·as recognised in classical Indian philosophy—pratyaks·a (perception) and anumāna (inference). Perception lies invalidated in the mūl mantar’s fifth phrase—with the deity shown as formless and beyond time, the very means to perceptual knowledge lie negated. This is why the text focuses on disproving inference’s epistemological claims. In the first line of Japjī’s first verse, Nānak says, “Thinking does not lead to thought even if one thinks a hundred thousand times.” Nānak makes the sole epistemic status of the written word and received authoritative testimony clearer at the end of the verse. Nānak has also written that the command (hukam) of the lord (rajā) has to be followed. A certain epistemological primacy is clearly accorded to the word and testimonial knowledge.

The word being the only valid epistemology, its utterance becomes imperative for knowledge, and Nānak shows in the third verse how one has to ‘sing’ about the lord to gain knowledge. And what does this ‘word’ comprise? The question Nānak raises in the fourth verse —“What words should be spoken by the mouth on hearing which [the deity can] have love [for the devotee]?”—gets answered in the same verse as “true name”. While knowledge itself is based in the name or the word, one can notice how Sikh epistemology adds to this the notion of testimonial authority or discursive competence, so that the word can only be spoken by the guru and not by just anybody.

In the sixth verse, Nānak makes it clear that the sound and the resultant knowledge can only come from the mouth of the guru. The role of the average person is to listen, and one can gain all knowledge from hearing the voice of authoritative verbal testimony, comprising the source of knowledge for Sikhism. Verses VIII to XI talk about the epistemic role of hearing or how one can gain knowledge from listening to the ‘name’ being spoken by an authoritative voice. Connected to this faculty of hearing is the faculty of ‘mannā’ (believing), because one has to unquestioningly believe in the authoritative voice for the word to be epistemologically valid. Verses XII to XV talk about the nature of believing, which also, like the ‘name’, cannot be spoken about by just anybody. The status of the word in Sikh epistemology is further highlighted as Verse XVI.19 of Japjī says the world was created through the word: “[The deity] created this expanse through one utterance (kavāu).”

Coming to Sikh ontology as articulated in Japjī, one can first comment on the nature of the deity in Sikhism, it being the very centre and the end of authority-based knowledge. Nānak lists in Japjī four features of the deity. The first is that it is self-generative and the second is that it is the supreme intentional agency, or the classical category of the purus·a, which renders qualities to all beings and objects, but which itself does not take any quality from anything. The third feature of the deity is that it is the single ontological category that gives unity to a multiplicitous reality: in Verses XVII and XVIII, Nānak shows how things around us are ‘asam˙kh’ (innumerable), while in Verse XIX, he shows how it is the ‘name’ that gives unity to this unmanageable multiplicity. The final feature of the deity is that, in spite of it being one and unificatory, it is limitless.

After elaborating on the central ontological category of the deity, I now move on to the next point in Sikh ontology as articulated in Japjī, which concerns a five-fold classification of the world, as described in Verses XXXIV to XXXVII. The five khan· d·-s or domains into which the world can be progressively classified are the dharam khan· d· (domain of religiosity), the giān khan· d· (domain of knowledge), the saram khan· d· (domain of labour and effort), the karam khan· d· (domain of action) and the sac khan· d· (domain of truth). Nānak says in Verse XXXVI, “saram khan· d· ki bān·i rūp” (XXXVI.3), or that “the domain of effort has the form of speech”, showing how effort, therefore, is in the linguistic labour of knowing the truth.

Also Read | The Kaur Of Patriarchy

Carrying this lingualisation of action further, Nānak says about the next domain, “karam khan· d· ki bān·i jor” (XXXVII.1), or that “the lingual form of the domain of action is power”. This attainment of power through linguistic action leads one finally to the fifth domain of ‘truth’ where the deity itself exists. The progressive intent of these five domains suggests that for Sikhism, religiosity is the most elementary quality, and that it should lead the individual through knowledge, linguistic effort and action to the ultimate category of truth. Truth being the ultimate category in Sikh ontology, one can now turn to its ethics, where obeisance to the testimonial, and cultivation of truth get prescribed as imperative.

Also Read | Road To Khalsa

How important a category truth is for Japjī is made clear right at the beginning of the text in the introductory śloka, which reads as “truth was in the very beginning, truth was in the beginning of the ages, / truth is what is, Nānak says what will be is also truth”. Nānak connects this ultimate category of truth with the ‘name’, the source of authoritative verbal testimony, in Verse IV, when he says, “the sāhib [lord, i.e. the deity] is true, the name is true”. The deity itself being truth embodied, the Sikh ethical imperative of pursuing the truth takes the form of obeying the deity and the voice of its authority. Verse XXXI says, “Nānak says that the true one’s [i.e. the deity’s] deeds are true, / obey its commands”, thereby making obeisance to the source of true authoritative testimonial knowledge the fundamental ethical principle of Sikhism.

Contemplating on the ‘name’ or the ‘word’ that is the source of all knowledge is thus Sikhism’s primary ethics, whereby following the truth and obeying the deity are both achieved. This insistence on passive obedience does not mean, however, that Sikhism is opposed to action. The Sikh ethics of action through truthfulness, humility and obedience is articulated in Verse XXVIII, and the insistence on non-ritualistic self-illuminatory action makes it arrive at its final ethical assumption—equality among all human beings, in Verse XXXIII.7: “No one is high (utam) or low (nīc)”.

I end this essay by repeating the simple assertion that in Sikhism the whole of the world is understandable through the word, and one can gain all knowledge, understand reality and be ethical through its exegesis, and with obedience to its linguistic authority.

(The writer is professor in the department of English at the Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi)