India’s 1962 debacle with China taught us that good neighbourly relations alone cannot secure the nation. Post 1962, we invested in developing capabilities of our armed forces, and within three years, in 1965 we gave a befitting response to Pakistan’s second attempt to wrest Kashmir by force. In 1971, India had a brilliant victory, secured the surrender of the Pakistan army, liberation of Bangladesh, and custody of 93,000 Pakistani PoWs.

Like 1962 proved a turning point for building capability for conventional wars, the February 14 terrorist attack by Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), supported by Pakistan, should be a watershed in our capabilities to deter and defeat hybrid war.

In 2001, JeM had attacked the J&K Assembly in Srinagar, followed by Parliament in New Delhi. Even though India reacted with full-scale mobilisation of its forces, the time taken to mobilise dampened the possibility of surprise and swift offensive.

India revised its strategy towards more proactive offensive operations, with available reserves and building up with strategic reserves. Pakistan evolved its counter strategy, called ‘new concept of war fighting’, essentially an attempt to constrict time and space for conventional war. Pakistan’s endeavour is fourfold: swifter mobilisation into critical sectors; redisposition of reserves to check Indian offensives; lower the nuclear threshold by bringing into play tactical nuclear weapons and enlarge scope for sub-conventional operations. Pakistan imagines a seamless integration of sub-conventional, conventional and tactical N-weapons into hybrid war. Concomitantly undertaken are information and cyber war.

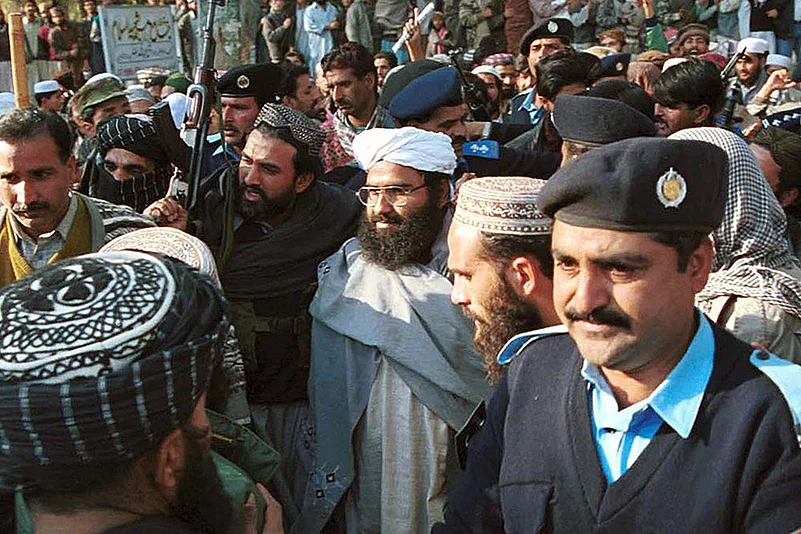

JeM chief Masood Azhar was captured in 1994 in Kashmir, and released in December 1999 in exchange for passengers of the hijacked Indian Airlines flight IC 814. Post the Parliament attack, Pakistan banned JeM, but Azhar Masood kept operating freely. He reportedly acquired a 4.5-acre compound in Bahawalpur for recruiting/training JeM militants.

Between 2002 and 2015, the predominant foreign terrorist group in Kashmir was Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT). In June 2013, the provincial government of Punjab headed by Nawaz Sharif’s brother Shahbaz, reportedly granted Rs 60 million to Jamat-ud-Dawa (JuD), headed by Hafeez Sayeed. JuD promotes itself as a charity organisation, but is the well-known front of the banned LeT, responsible for the 26/11 attack.

Driven by internal dynamics in Pakistan, the predominance in J&K operations progressively passed on to JeM around 2015. The Pathankot Air Force station attack on January 2, 2016 was their major comeback. They have since ridden on the radicalisation wave to attract youth from Kashmir. One of them was terrorist Adil Ahmad Dar, who executed the car bomb attack on February 14.

Terror groups such as LeT, JeM and HM are like multi-headed hydra, powered by Pakistan, supported by China, and funded by some West Asian states. Bans imposed by Pakistan are a farce and international sanctions, too, make little difference.

Consequent to the Uri attack in September 2016, India responded with a series of surgical strikes across the Line of Control, which were a resounding success. However, within a couple of months, terrorists struck at an army camp in Nagrota. The Pakistan-terrorist-separatist nexus worked overtime to destabilise the situation. The by-elections in April 2017 saw a drop in voter turnout—7 per cent, from the 70 per cent achieved in the 2014 assembly elections. In July 2017, an Amarnath Yatra bus was attacked for the first time. Local recruitment of terrorists reached new heights. Clearly, effects of the successful surgical strike were not sustained.

The recent talks with Taliban and the announcement of US withdrawal from Afghanistan have given a fillip to Pakistan. It provides leverage to divert terrorists into Kashmir, reminiscent of the effects of the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan. Pakistan is further emboldened by Chinese interests in making peace with terror, hoping to keep CPEC secure and insulate the restive Xinjiang province from terrorists’ groups. The growing proximity of Russia with Pakistan, and their strategic interests in Afghanistan, add to India’s challenges.

Diplomatic measures to declare Masood Azhar a ‘global terrorist’, creating pressure on China, may help but has limited value. In any case, his proteges are waiting in the wings to carry his mantle. Financial sanctions against Pakistan will help, though superpowers who view relations with Pakistan as “deeper than the ocean and higher than the sky”, should be expected to stand by them.

As for a military response, Prime Minister Modi has declared his political will. “How, when, where and who will punish the killers and their promoters will be decided by our forces, who are capable of dealing with the situation”. The armed forces will determine their response, keeping in mind ‘efforts to effects ratio’, domination of conflict domains, response to escalation, and mission outcome. While objectives, timing and surprise are critical, an ‘all or nothing’ approach could prove counterproductive. Specific gains made swiftly with information dominance would yield better dividends.

In order to sustain the gains from military, diplomatic, and economic actions, it is important to recognise that this hybrid war is thriving on fault-lines within. Currently, the battlefield is Kashmir and its immediate vicinity. While immediate vicinity to the west is PoK, Jammu to the south has a crucial role to play. India’s strategy to defeat this hybrid war must first secure Kashmir and its immediate vicinity. Unlike a classic battlefield, mind space is more important than physical space in hybrid warfare.

The fact that Adil was a local fidayeen must be a wake-up call for countering indoctrination-radicalisation. Less than four years back, an Army recruitment rally, with little over 50 vacancies, had 20,000-plus motivated youth queuing up to enlist. That has changed. Pakistan, in collaboration with the terrorist-separatist nexus, has launched a very targeted campaign to vitiate minds of youth through propaganda. Elements known to be radicalising—separatist leaders, religious leaders and ‘overground workers’—must face severe punishment.

A counter indoctrination-radicalisation drive is important. Multiple Central initiatives are not being projected as part of a larger national narrative. It is crucial to have a empowered central agency to monitor the impact of initiatives of various ministries and institutions and undertake an effective information campaign. There is a sizeable population of Kashmiri ex-servicemen from the Indian Army and paramilitary forces—an untapped national asset which can be harnessed for integration.

Less than a month back, the Ashok Chakra was awarded posthumously to Lance Naik Nazir Ahmad Wani, a surrendered militant who later enrolled in the Territorial Army. Nazir was earlier awarded Sena Medal twice for gallantry. Kashmir has many role models who can be promoted to inspire youth.

A young techie developing drones in the film Uri: the Surgical Strike, can be transformed from fiction to fact. Israel gained technological edge in warfare through constant movement of operationally experienced men and women from Israeli Defense Forces into industry and academia. Hybrid warfare requires a ‘whole nation’ approach. Cyber and information space are critical in hybrid warfare. India’s excellence in these domains needs to be harnessed.

After the September 2016 surgical strike, it was distressing to witness the squabbling over its proof. Unity within the country is more important than international support. Post the February 14 attack, it is heartening to see the country united. This solidarity must sustain through the immediate response of punishing perpetrators of the attack, and channelled further towards defeating the hybrid war, rather than allowing it to smoulder in perpetuity.

(The author is former deputy chief of army staff and Kashmir corps commander, and currently member, National Security Advisory Board)