Farmer leader Rakesh Tikait's combined call of "Allahu Akbar" and "Har Har Mahadev" at the Muzaffarnagar mahapanchayat on Sunday may have created a stir -- but it did not come out of a vacuum. Nor was it a sudden turn.

A flashback to 2018 -- via two Outlook ground reports -- and to a cover story in February this year will help elucidate this.

The first article 'In Lieu Of Courting Justice' from February 2018 offers an in-depth picture of a bilateral effort to create a rapprochement between local Hindus and Muslims in this sugarcane belt. It was a difficult process -- given the history of violent conflict and displacement. But importantly, it was an effort led by the Hindu Jat community, and Muslim participation, even if hesitant, bore signs of a possible amity.

The second report 'Unity’s Field Test' from May 2018 points towards the harvesting of what was sowed in that common aspiring for an entente. This gives us a micro picture of the complex social dynamics at play just before the byelection to the Kairana Lok Sabha constituency, next door to Muzaffarnagar.

Significantly, a joint opposition front -- with the SP, BSP, Congress and RLD coming together -- had dared to put up a Muslim woman candidate, a Gujjar by caste.

Even more significantly, she managed to defeat the BJP candidate, also a woman, and also Gujjar. One pointer to the complex, overlapping community lines in these parts: both candidates, one Muslim and one Hindu, shared a common great-grandfather!

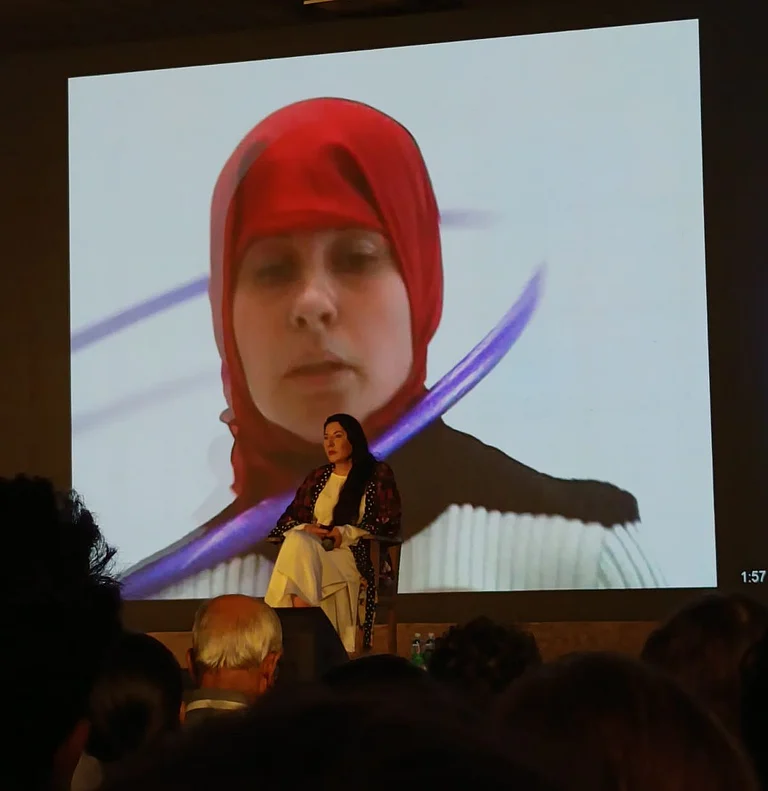

The Outlook cover story 'Running On Jat Fuel' from February 2021, around the onset of the farmer protests, brought these strands together again. This is when we saw a Muslim leader being invited to address the rally as one of the main speakers, before Rakesh Tikait's brother, Naresh, with a large number of Muslims in attendance.

Two narratives intermingle here. One is the macro story. After the Muzaffarnagar riots of 2013 violently altered the equations between Jats and Muslims in western UP and beyond, it had become symbolic of the en masse Jat movement towards Hindutva in the last decade. The effects of that were visible in the Lok Sabha elections of 2014 and 2019, and the Uttar Pradesh assembly election of 2017.

Kairana 2018 was a pattern-breaker, for the constituency again voted BJP in 2019. The SP-led opposition alliance and Congress fought separately this time, even if their combined vote share still touched 48.41% against the BJP's 50.44%.

But beneath that larger picture of electoral politics, there has been a complex narrative unfolding on the ground. This flows more from a socio-economic logic than one relating to party affiliations. Barring a minority of land-owning Jat Muslims, the majority of Muslims in this broad rural swathe were traditionally farm labourers who worked on the fields of Hindu Jats, the most powerful community in a region that's actually a mosaic of castes and communities, with varying (and shifting) political loyalties. The wholesale displacement of Muslim labourers had upset the farm economy, leading many Jats to introspect over the wisdom of their past actions.

This is the ground from which Tikait's call emanates. It not only harks back to his father Mahendra Singh Tikait's approach, as he himself took pains to point out, but speaks to a live, unfolding situation. The farmer protests again bring an economic logic to the foreground, with a shared source of distress. Will that trump religious affiliations in the coming Uttar Pradesh assembly elections?