With the top hat, ’tache and three-piece, Gopinath Muthukad almost looks straight out of a Lee Falk comic panel. Almost. “Sorry, I didn’t bring my cape,” Kerala’s most famous contemporary magician says. The late-noon throng of school kids doesn’t care. As the meme goes, not all heroes wear one. And, anyway, Muthukad is more David Copperfield than Mandrake. Like the illusionist icon, he operates in the gulf between science and superstition. His currency: vismayam. Wonder.

Right now, he’s operating on two hours of sleep and as many cuppas. The showman’s ease fine-tuned over a decades-long career—some 8,000 stages in over 50 countries—barely masks the toll of a red-eye flight. But the show must go on. And today’s was especially important—both as culmination and vindication of six months of work and years more of planning. Students of Muthukad’s Different Art Centre—a project to nurture the talents (magical and otherwise) of differently-abled children—have just put up a spirited, non-stop, hour-long magic performance.

Understandably, it’s all Muthukad can talk about. “They are going to be featured in <<India Book of Records>>,” he beams. In an office space chock-full of grand honours and paeans to hard work—including the Merlin award he won in 2011, becoming, after his one-time guru P.C. Sorcar Jr, only the second Indian to win the ‘Oscar’ of magic, this latest feather-in-the-cap fits right in.

“Magic is a kala and a shastram, perhaps the only one that is both. And as such, it can be learned through practice,” says Muthukad, the biggest thing to come out of Nilambur, Malappuram district, since teak. So ‘vanishing’ the odd elephant or state minister is not mass hypnotism? “More like misdirection: smoke and mirrors, tone of voice, body language, visual cues and hand gestures... I have never claimed to have powers,” he laughs. Still, it takes some serious training to pull one over on audiences itching to call a magician out on any ‘hokum-pocus’.

“Magicians look for the blind spots in people’s perceptions, identify vulnerabilities and edges in their mindscapes so as to subtly push them toward these limits—making them susceptible to suggestion without realising it,” he says. His two-and-a-half-hour performances today nod to such staid conventions in the craft: co-mingling aspects of sleight of hand and mentalism among other feats of spiel and prestidigitation (think Deepak Chopra and parlour tricks) into ‘thought experiments’ that leave audiences—which typically range from boisterous chavs and cynical hipsters to unsmiling sceptics and hardened politicians on the receptivity scale—agog as opposed to simply agape. “I want them to ask about the ‘why’ of the thing as well as the ‘how’. I want them to engage with it both emotionally and intellectually,” says Muthukad.

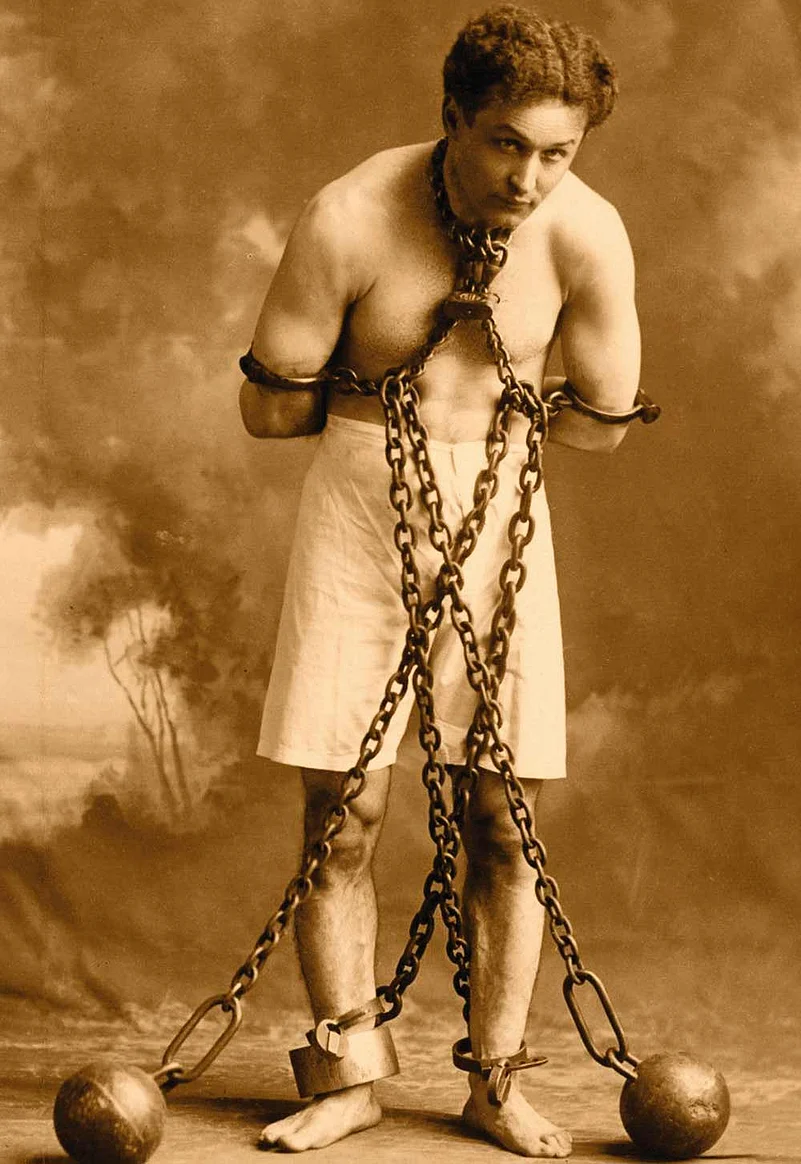

Since audience interactions at magic shows are pastiches of ceded agency and control, aspiring to that kind of subtle engagement surely requires something more the two hours of practice he puts in daily—an hour each before bed and on waking up without fail. If anything, should it not warrant the sort of rigorous prep he undertook for the escape acts that for so long dominated his oeuvre? “What, being handcuffed, bound in chains and locks, feet tied together, and hung upside down from a tree for hours on end? It took nearly two years to work my way down from needing three hours to free myself to doing it in under a minute,” he says, somehow wearing the perma-smile while stifling a yawn. “And I’m no spring chicken anymore,” the 55-year-old adds.

Gopinath Muthukad with children aftera show

Age, and the accompanying diminishments, has mandated this tonal shift. As has fatherhood, but also other responsibilities: as the hands-on founder of Academy of Magical Sciences—the 1996-built school in Thiruvananthapuram likened to ‘Hogwarts’ that has graduated over 20 cohorts of Kerala University-accredited magicians, as a UNICEF partner who helps bring cheer to flood-hit areas and as the creator of ‘Magic Planet’. This is his “Shantiniketan”, a Rs 15-crore ‘edutainment’ park on the city outskirts that is a ‘Rogue’s Gallery’ and retractable mountain driveway away from passing for Xanadu. Built on sweat, disposed-of family property and pawned-off wedding jewellery, it turned five years old on October 31: Halloween to some, but to magicians, the day Houdini died. An assistant, no Lothar (but who is?), interrupts to ask about lunch. The chef may not be a Hojo (again, who is?), but can supposedly whip up a mean biriyani.

Raconteurship is second nature to Muthukad. His late father, Kunjunni Nair, who figures often in his stories, was much the same. A repository of folklore, Nair remains his son’s conscience-keeper and moral compass. Wistfully, Muthukad recalls how, after a hard day’s work on the farm, Nair stoked young Gopi’s love for magic with easy-chair yarns about ‘Kerala’s father of magic’ Vazhakunnam Neelakandan Namboothiri. How as a five-year-old, he stole Rs 25, a tidy sum in 1969, from his father when a snake charmer agreed to teach him how to “move a lemon on command” and in middle school, ‘traded’ his father’s watch for a classmate’s Dubai-bought magic slate. Muthukad weaves such tales as exposition in his practice too, between the hype video—with disembodied cheers and rock anthems scoring visuals of past triumphs, sequined jadoogirls and the kitschy pageantry that so easily buries breathless derring-do physicality under a pantomime stage-show banality.

As we take a brisk walk in the park (to make up for the missed daily morning jog), taking in such traditional Indian magic forms as the rope trick (a variant of the act that doesn’t involve the characteristic downpour of human limbs) and even Kerala’s own ‘Green Mango Tree’ trick (an elaborate show involving the coaxing of a fruit-bearing tree out of a mango seed), Muthukad is in his element. When speaking of the nearly 50 street practitioners from across the country housed in the park, he reveals that his father didn’t think much of magic as a career choice and refused to talk to him after he dropped out of law school to pursue his dream. “We have here the only street magicians probably anywhere who pay income tax. Besides paying them salaries and sending their kids to school, we help preserve these Indian traditions. The tragedy of street magic is how easily it is dismissed as trivial. Our hope is that their children understand they are heirs to a rich legacy. That what their parents do is worthwhile,” he says.

The relationship healed, but not before a dearth of opportunities and worsening finances drove him to attempt suicide. “Creditors were hounding me and I found only closed doors wherever I turned. My father refused to acknowledge me. When I couldn’t take it anymore, there was nothing but a friend out on an evening stroll to keep me from grabbing a transformer wire,” Muthukad says. He goes quiet for a minute. It’s a long minute. “Lunch?”

It isn’t the easiest thing in the world: to follow up a story about potential suicide. The chicken biriyani and walk-whetted appetites help. “That wasn’t even the closest I have come to being electrocuted,” Muthukad says matter-of-factly. If you let slip about a self-harm episode, I guess you could do worse than segueing into other near-death experiences. This one is in 1996 – a few months after his marriage, when performing a Houdini special, the ‘water torture escape act’, in Kozhikode. Cuffed, stuffed into a knotted plastic bag and lowered into a flooded glass tank, He has a minute to get out before the 30-kg spear overhead skewers him. And an electrical current is passed through the water, for good measure. “There’s a hidden key for the handcuffs and a knife to cut the bag. The seconds tick by and a light behind the audience that signals the all-clear to go into the water doesn’t turn on. At that point, I was just choosing how to go. A friend noticed and yanked the plug. I was out of the water at 57 seconds. It was a close call. The chances of survival in such acts are about 50-50,” says Muthukad, unable to stifle the reflexive shudder. He is, though, more blasé about getting singed by the pyrotechnics that accompanied the spear’s descent. “If I failed, the sympathy would have stung worse.”

Harry Houdini

It was replicating another death-defying Houdini trademark – the ‘fire escape act’, which saw him chained and lowered by crane into a straw tee-pee that was then doused in kerosene and set ablaze—that in 1995 turned him into a celebrity. Like Houdini, whose books line shelves in both his office and 3BHK flat, Muthukad vowed never to do it again. “I broke that pledge in 1998 for a show in Bahrain and nearly paid the price. They used hay and petrol, both of which burn faster. As I freed myself, a blaze hit me and I lost consciousness. I was hospitalised with burns to the face and hands,” he recalls. It may not have been hubris, but (as the backs of his hands can attest) very nearly as fatal a flaw.

So why persist in attempting these and other such dangerous acts like ‘bullet roulette’? Between sips of his fourth tea, Muthukad references the famous quote frequently misattributed to post-summit Edmund Hillary: “Because it’s there.” Point taken. Ask how he does it and the retort is cornier: “Very well, thank you.” The flippancy and deflective humour are part of his carefully constructed persona: a brave front to “never show your audience if you are upset or hurt”. A lesson he learned from his baptism-by-fire solo debut as 10-year-old ‘Master Gopinath’—assistant to revered magician R.K. Malayath. “The show flopped. I ran backstage in tears, but my father – who had a suit specially tailored for me—told me that such defeats would help me learn and grow,” Muthukad says. Prospero, the Shakespearean sorcerer whose cut-out casts a shadow over the park even in the dusk, would approve.

These are but peeks behind a mask that only really comes off at home where he instructs his son, an aspiring “card-ician”. Or, in private moments at the academy next door, where he has a secret spot for quiet reflection. With these, as with trade secrets, Muthukad is a miserly sharer. After a taxing photo shoot, I chance one final ‘how do’ question. And at last, an exhausted Muthukad falls back on that tired trope: “A magician never tells.”

Also Read:

By Siddharth Premkumar in Thiruvananthapuram