In the wake of the latest report by the United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA), India and China each comprises about 18 percent of the world’s population of 8 billion. It means more than one-third of humanity lives in these two countries only. Both countries are demographically powerful and economically rising. There are speculations about what is going to happen in the next few decades to both countries in terms of economic power shaped by demographic dynamics.

It is important to mention that the world is passing through new demographics not alone determined by the size of the population and growth but by the composition and distribution of the population. Changes in the age composition of the population popularly associated with the demographic dividend and the distribution and redistribution of population unleashed by urbanisation are additional dimensions to understand the relationship between population and development.

The demographic dividend is the result of demographic transition and the consequent age-structural changes leading to the rising ratio of the working population and the declining ratio of the child population. During the early phases of demographic transition, the ratio of the old age population grows very moderately.

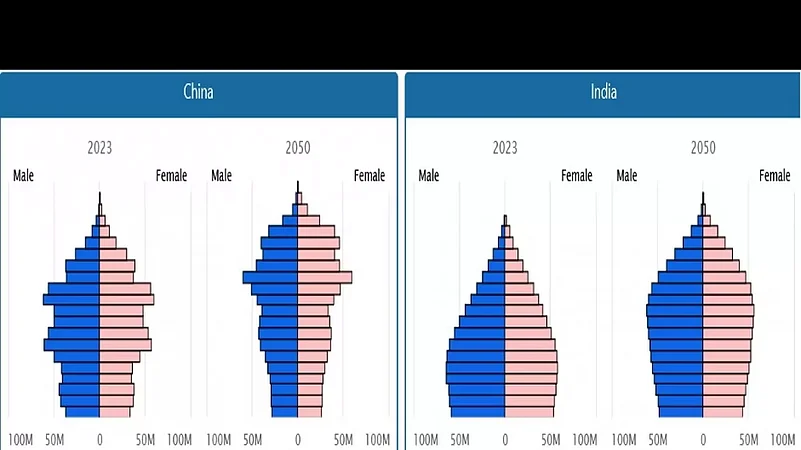

In China, the ratio of the working age population (15-64) is 69 per cent in 2023 compared to 68 per cent in India. By 2050, this ratio will decline to 59 per cent in China, whereas this would be nearly constant for India. As such, the ageing of the population in China would be very fast and the median age of the population of China which is 39 years in 2023 compared to India’s 28 years will increase to 51 years in China in 2050 compared to 38 years in India. India’s population thus continues to be young and energetic for several decades to come. This could be understood through the changes in the age-sex pyramid depicted in Figure 1.

Similarly, mobility and urban transition in China have almost doubled with the level of urbanisation in China is 63 per cent in 2023 compared to 34 per cent in India. Thus, the demographic advantage in the form of a demographic dividend underscores the fact that increased labour supply will increase the production of goods and services. However, this may not be realized automatically but depends upon the right economic and social policies taking into consideration the demographic opportunities intertwined with mobility and urban transitions.

FIGURE 1: Population Pyramid, India and China, 2023 to 2050 (Source: US Census Bureau, International Database.

The debate on the relationship between population and development is not new but needs to be understood in the changing context of demographics. Not equipped to understand the holistic nature of demographic dynamics, there is often an alarmist concern raised by researchers, policy makers, journalists, and the media focusing only on the single attribute of the size of the population bereft of the consideration of the composition and distribution of population. The more recent debate in demography is however concerned about the composition of population theorised in the form of demographic dividend and distribution of population manifested in the form of urbanisation.

The composition and distribution of the population are strongly determined through migration influenced by the demand and supply of labour and labour market characteristics, urbanisation, and the emerging rural-urban divide in the country. In such a situation, the population size alone is not the sole determinant of economic growth and well-being. A space, place, and regional approach focussing on demographic diversities, decentralised planning, and governance with a focus on human development will go a long way in utilising the demographic resources for the peace and prosperity of India.

The demographic knowledge about size and growth has a colonial history to divide and rule and also held responsible the people of the colonies for their poverty and underdevelopment. It tried to relate economic growth on a per capita basis, concluding that population size and growth are barriers to development. This is the Malthusian notion of population that stands negated by many reputed scholars like Ester Boserup and Julian Simon. Boserup showed that population growth and consequent rising density was a critical factor in the promotion of agricultural technology and innovations. Population growth induced agricultural growth, and there were instances where sparsely populated areas lagged in human progress and development.

Another emphatic work by Julian Simon (1981) also showed that people are the ultimate resource, and a growing population is necessary for material advancement. People are not only consumers but producers as well. Researchers before Thomas Malthus (1798) like William Petty, known as political arithmeticians, declared almost three centuries before, that the nation’s power lies not in the size of territory but in the composition of the population engaged in trade, commerce, and industries.

It is also very important to mention that population size and growth are the result of a combination of demographic processes known as fertility, mortality, and migration, and not the product of fertility alone. Ironically, researchers who are dismayed by population size forget that fertility, whether measured either in terms of Crude Birth Rate (Number of births per 1000 population in a year) or Total Fertility Rate (TFR) (average number of live births per woman) has always been declining.

There is hardly any fertility increase in human history, and once fertility starts declining, it is almost difficult to reverse. Many advanced countries in Europe and Japan are struggling to increase their fertility levels, and the pro-natalist policies hardly work. The recent data from National Family Health Survey-5 shows that

India has reached replacement level fertility (TFR 2.1) at the national level as a whole and also in most of the states of the country.

Further, it is worthwhile to emphasise that fertility alone is not responsible for population size and growth rate. One has to recall the demographic transition theory to understand the role of mortality and migration in determining size and growth. The demographic transition theory was developed in the 1940s resulting from the study of the demographic transition in Western Europe that took place almost two hundred years before. Ironically, this grand theory has served as a small analytical tool in the public discourse on population size and growth without having a discussion on the integration of fertility with mortality and migration. The public discourse on population size and growth based on size attributing to fertility level is methodologically flawed and politically articulated to be ‘anti-poor’ since the time of Malthus.

It is promoted by colonialism, and researchers trained in a colonial mindset tried to look at population size and growth in an atomistic way. It has diverted attention from investment in human development sectors like health, education, and skill development by holding population growth responsible for economic backwardness and poverty. It is also often argued to have used coercive measures to control the population, violating reproductive and human rights.

The same argument is also used to explain environmental degradation and climate change holding population size and growth responsible. It also portrayed rural to urban migration resulting from distress due to population growth in rural areas and depicted urbanisation in a negative form.

To conclude, it is important to realise that a ‘New World Demographic Order’ has been emerging which warrants not only economic and social policies to harness the demographic opportunities at the national level but also to fulfil the shortage of human resources across the globe unleashed by rapid ageing and rising aspirations shaped by mobility and urban transitions.

(R.B.Bhagat is Former Professor International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai.)