Amar Bahyer Rokte Rangano Ekushe February,

Ami Ki Bhulite Pari?

(Drenched in Blood of my brothers, how can I forget 21st February?)

These lines by Abdul Gaffar Chowdhury still resonate through Dhaka's streets when they recall the bloody days of war for protecting Bengali against the imposition of Urdu by Pakistani authorities. While the day marked one of the heinous crimes in the history of Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan), its recognition by the United Nations as the International Mother Language Day in 1999 healed the wounds a bit.

On February 21, 1952, when students from Dhaka University tried to storm the Assembly building of East Pakistan, police opened fire and a number of students were killed, including Abdus Salam, Rafiq Uddin Ahmed, Abul Barkat and Abdul Jabbar. Their offence was to protect their language - Bengali. The other bodies went missing and the search for a dignified burial went on.

The protest took its shape in 1948 when the Government of the Dominion of Pakistan declared that Urdu would be the national language of the state sparking protests among the massive Bengali populace of East Pakistan (now, Bangladesh). The demand to add Bengali as at least one of the national languages was raised by Dhirendranath Datta from East Pakistan on February 23 1948, in the constituent Assembly of Pakistan. The proposal soon catapulted a mass protest where large sections of Bengali students from Dhaka University organised a demonstration demanding the recognition of their language.

On the D Day- February 21 in 1952, the protest reached its climax when the Pakistan government tried to outlaw the students by opening fire at them. Following years of conflict, in 1956, the Central government granted Bengali its official status. However, the Bhasha Andolan Dibash or the Language Movement in East Pakistan catalysed the assertion of Bengali national identity in East Bengal and later East Pakistan, and became a forerunner to Bengali nationalist movements, including the Bangladesh Liberation War.

In 1999, UNESCO declared February 21, International Mother Language Day which is observed worldwide to promote linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism.

It has been over two decades since then but the fear of losing linguistic identity continues to prolong agitations and violence among communities which share many social and cultural affinities. An example of the same is visible in the current socio-political narrative where Hindi is being pushed by the Centre as Rashtra Bhasha creating a spectre of language imperialism haunts the Indian Union.

Language is among the most powerful and emotive mediums of both individual and national consciousness, a reservoir of a living memory spanning centuries. While political masters can introduce any arbitrary insignia to a population and expect them to follow it, it fails when it comes to imposing a language, that is not rooted in the soil of a person’s land.

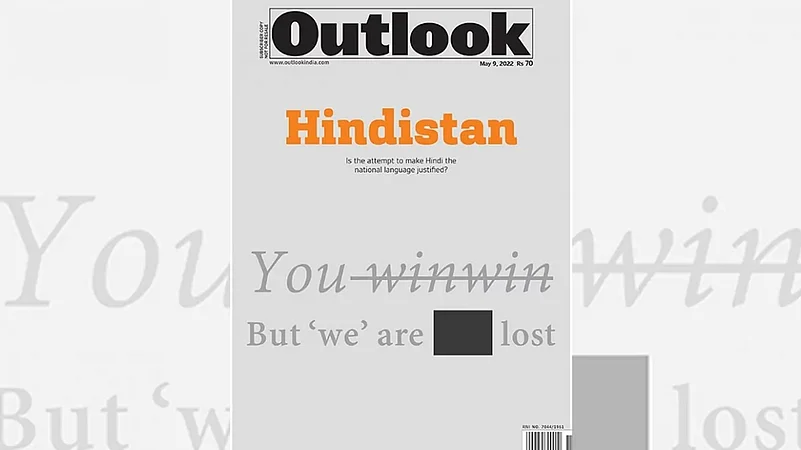

While there is an effort to promote the same and use one language to build a narrative of political unity, on International Mother Language Day, we look back on our May 9, 2022 issue, ‘Hindistan’, exploring the politics of language. As advocates of regional languages gear up to face the threat of a Hindi deluge, they are also waking up to the existential threat of internal decay. We look at the contradictions kindled by the controversy.