In the last eight years, the modus operandi of the BJP-led Central government has been obvious: to experiment with marginalised communities on issues related to the rights of citizens and to encroach upon the autonomy of states, even though both are unambiguously protected by the Constitution of India. It has been a discernable pattern, one that the political Opposition has been unable to counter by educating the affected communities and organising the state governments to resist centralisation. The erstwhile state of J&K has been an important laboratory for implementing this trial and error method because both community diversity and state autonomy were protected and guaranteed to the state. The state no longer exists, of course, but the BJP's experimentation in J&K, nevertheless, has been relentless.

The most recent example of one such experiment has been the introduction of a Private Member Bill in the Lok Sabha on April 1, 2022, by Member of Parliament Jamyang Tsering Namgyal, seeking the inclusion of the Bhoti language in the 8th Schedule of the Constitution of India.

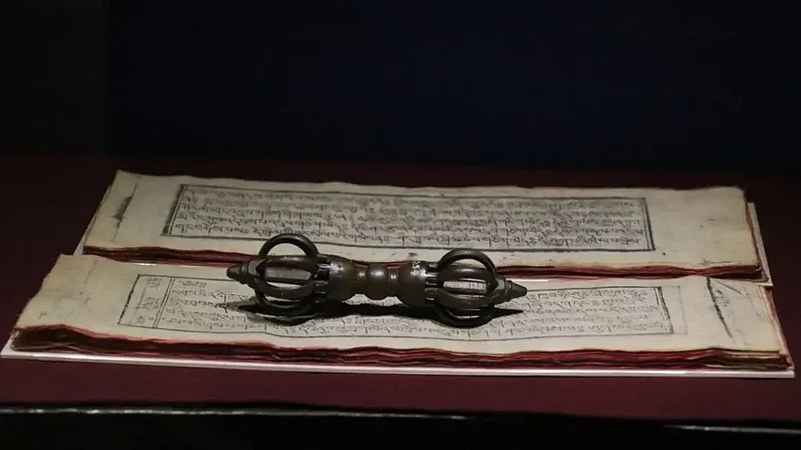

In letter, the need for such a Bill cannot be disputed. Buddhism, and especially Tibetan Buddhism, has been among the richest contributors to knowledge and wisdom in the world--not merely “Himalayan history and culture” as argued by Mr Namgyal in his Bill--a process that took place from the 1st century CE to 6th century CE in and around the western and eastern Himalayas. One significant method by which this was done was by translating Sanskrit texts into Tibetan. The translations were so precise and faithful that more than a thousand years later, it has been possible to reconstruct and “re-translate” long-lost texts back into the original Sanskrit from Tibetan.

In spirit, however, the introduction of the Bill has witnessed a roiling dispute in Ladakh, a Union Territory that is demographically tiny, territorially massive and strategically crucial. At the centre of the controversy surrounding Namgyal’s Bill is the use of the Sanskrit word Bhoti to define the language; the implied insistence (erroneously) on equating the language exclusively with Tibetan Buddhism; and the false claim that “[T]he glory and grace of this language is not only confining (sic) to the Himalayan region[s] of India but also in Bhutan, Nepal, Tibet, China, Mongolia and Pakistan”. This long view of history has repercussions both immediate and long term: the use of Bhoti to define the language is being challenged within Ladakh itself. The claim that Nepali, Chinese and Mongolian are “Tibetan” languages in any sense will be opposed down the line. Both are the Ladakhi MP’s version of Akhand Bharat.

The Bill has merit. But it is deeply flawed by the evangelical zeal of the MP who has introduced it. To understand the Bill’s merits and grasp the dangers of the method deployed, it is important to understand the brewing controversy at several levels. To not do so is to risk further fragmentation and disturbance in a borderland region and, in time, the entire Himalayan belt. The debate deserves some elaboration, however brief.

First, it should be stated that there cannot be any objections from the citizens of Leh and Kargil--whether Buddhist, Muslim or Christian--to the inclusion of Tibetan or Ladakhi, a dialect of Tibetan, in the Schedule of Official Languages of India.

All Ladakhis are united on this score. Indeed, as already asserted above, the demand should not be based merely (I use the word advisedly) on the demographic size of its speakers, but on the immense contributions of that language to the intellectual history of India and the world. It is well known that while Buddhism originated in India, within 600 years of its Mahayana articulation, it had spread to China, Tibet and Japan, each of whom synthesised its teachings into expressions that, while always paying heed to its origins, “translated” its expressions into new flowerings. Today, the adherents of Buddhism make up one of the world’s largest trans-national religious communities. In this context, the language (to repeat, not merely the script) needs urgent recognition so that it is not assimilated into a false unity that could endanger the uniqueness of wisdom that has blossomed over more than two and a half millennia.

Second, the controversy over the Bill is a classic case of the fuzzy intent of the Bill. If the word Bhoti is being used to designate a language, then the correct word to use for such legislation would be “Tibetan”, “Ladakhi”, or even “Pod-skad”, the Ladakhi word for Tibetan, as has been argued in a Facebook post by Nawang Shakspo, a former Ladakh Director of the J&K Cultural Academy, an author and the publisher-editor of The Ladakh Review. In fact, he emphatically declares, correctly, that “there [does] not exist any language under the name Bhoti”. This contention is a reaction to the Private Member Bill’s Sanskritised name for the language, as opposed to the name given it by the native speakers of this Tibetan dialect.

The third cause of the controversy is political perception. To the Ladakhi ear the word Bhoti, the Sanskrit word for the Tibetan-speaking peoples of the pan-Himalaya, implies a religious affiliation to Buddhism. This is not true, of course, for all Himalayans, since there are also Muslim, Christian, Hindu and even Sikh speakers of Ladakhi. And, we might add, adherents to Buddhism in other languages of the Himalaya. The conflation of language and religion, therefore has resulted in suspicion, which transforms debate to antagonism. Ambiguities are addressed through discussion, but that militates against the BJP’s tendency to gloss over, even prevent, nuanced discussion, when laws, statutes and regulations are at stake. This has led to a stiffening of positions among the growing Opposition to the BJP's ruling dispensation in the Union Territory. So, for example, the Bazme Adab, Kargil’s premier literary organisation, has categorially echoed the assertion by Shakspo in their letter to Ladakh’s Lieutenant-Governor, objecting to the Bill. “Bhoti is neither a script [n]or a language of Ladakh”, they have argued, and have highlighted the equal importance of some other languages spoken in Ladakh and the western Himalaya, including Dardic and Shina.

To summarise, the language controversy in Ladakh cannot be taken lightly as it initiates a fresh source of fragmentation, this time along linguistic lines. Regardless of what his reasons or who his supporters are, Mr Namgyal, has alienated significant segments of the population in Leh and Kargil districts, something that is avoidable in this strategically vulnerable borderland. It is true that the LBA, or Ladakh Buddhist Association, recently held a rally in support of the inclusion of the language in the 8th Schedule of the Constitution. But the rally was held to affirm the uncontestable importance of the language and not to support the exclusion of other religious communities of Ladakh.

A recent report rhetorically asks whether the “historical unity” that was forged between Leh and Kargil last year could “withstand the storm” raging in Ladakh’s plural society over the hazy intent and perception-challenging Bill. To allow it to do so would be tantamount to confirming the wit of the date, April 1, on which the Bill was introduced in parliament. In the interests of all Ladakhis, the hullabaloo must not be allowed to break that unity.

(Professor Siddiq Wahid is a historian of Central Eurasian and Tibetan History, professor, author and frequent commentator on the politics, histories and cultures of the Himalaya and South Asia. Views expressed are personal.)