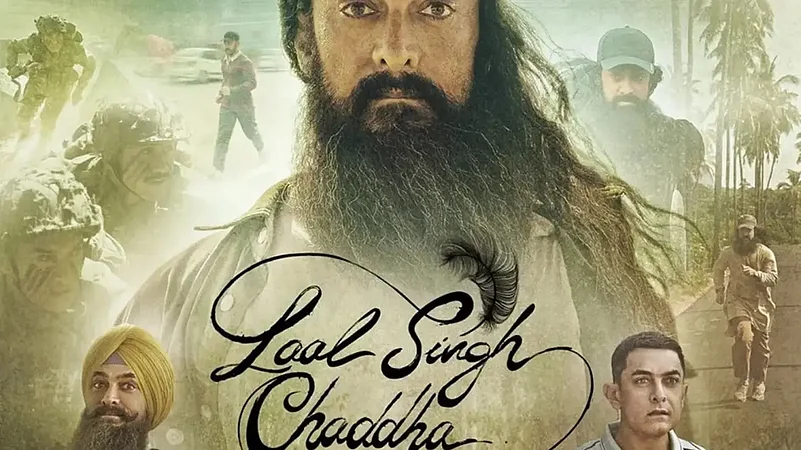

The social media campaign ‘#BoycottLaalSinghChaddha’ and the kind of support it is getting from the masses are indeed alarming. More than 2,00,000 netizens (many of whom are the supporters of the Bharatiya Janata Party) have tweeted in the last few days giving a call to boycott Aamir Khan’s film Laal Singh Chaddha, which released last week.

The boycott call, however, unlike some previous instances of this kind, has nothing to do with the content of the film. A seven-year-old remark of Khan (in which he expressed his growing sense of ‘fear’ about living in India) has been picked up by the dissenters to motivate others to boycott the film. The same call has also been given for Akshay Kumar’s film Raksha Bandhan, whose writer Kanika Dhillon’s four-year-old tweet about ‘gau mata’ has been spotted as being ‘Hinduphobic.’

Banning or boycotting a film is not a new thing in India. Sometimes films have not been cleared by the Censor Board, sometimes even after approval of the Censor Board, films were banned by some state governments and at other times, public calls for boycotting a film were given. Reasons for banning or boycotting a film are varied that range from objections to alleged religious insensitivities to sexual content. The list of such films is also long and includes some classics like Deepa Mehta’s Fire and Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmaavat.

A call for public boycott is, in fact, more dangerous than a state-ban. In case of a state-ban, the producer can go to the court and can exercise the right to self-defence. The film Aarakshan (featuring Amitabh Bachchan, Saif Ali Khan and Deepika Padukone), for instance, got a verdict in favour of its release from the Supreme Court when it was banned by some state governments. But in case of public boycott, judiciary remains helpless. Jodhaa Akbar, for instance, was not released in Rajasthan because of the protest of the Karni Sena. Sometimes, to save a film from huge financial loss, even mediation of political leaders has been sought by the film producers. In the 1990s, Maniratnam’s team had to meet the then Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray for getting Bombay released.

In fact, in case of targeted social media campaigns, which now play the most important role in giving a call for the public boycott of a film or trolling it, scope for logical argumentation is a rarity. Logic can seldom stop trolling armies who in well orchestrated ways operate often as a part of the IT cells of different groups and political parties.

In fact, when Jurgen Habermas argued that the 18th century Europe saw the birth of the ‘public sphere’ as opposed to the private sphere and highlighted the crucial role played by the coffee houses, salons and periodicals in forming the public sphere, he could not imagine that the public sphere in the new century would produce new virtual spaces like Facebook and Twitter which would become more powerful and effective in forming public opinions than clubs, coffee houses and saloons.

This is also interesting that ‘#BoycottLaalSinghChaddha’ campaign is more active on Twitter than on Facebook. Twitter, in fact, as a platform allows less space for debates than Facebook as it has the constraint of words. Twitter, instead of allowing debates to take form, often, because of the sharp and pointed comments that it features, promptly contributes to the formation of public opinions without serious contemplation on an issue. On Twitter, netizens, who are aggressively operating the ‘#BoycottLaalSinghChaddha’ campaign, are citing ‘hurt sentiments’ as their only reason for spurning the movie.

Sentiment, if not nurtured by reason, is often misleading. Even a decade ago, media and intelligentsia played crucial roles in the formation of public opinions. Now Facebook and Twitter have made everybody an expert in everything. Habermas saw the birth of the public sphere as a movement towards democracy. It indeed was. But in that move towards democracy, intelligentsia played a vital role. In early 18th century England, for instance, Addison and Steele were the key figures who through periodicals like The Spectator and The Tatler significantly contributed to the formation of public opinion. Social media have made the role of the intelligentsia almost insignificant in the formation of public opinion now. Social media democracy has indeed emerged as a classic example of a flawed democracy.

Some of those who have criticised the boycott campaign against Laal Singh Chaddha have argued that a ‘collective art’ like cinema should never be boycotted for one individual’s involvement in it. Trade analyst Komal Nahta has remarked, “Film industry is not just about the stars. It is about lakhs of people who depend on the industry. A film has a crew of about 3-4,000 people working on it. By boycotting Laal Singh Chaddha, you are not boycotting Aamir Khan, you are boycotting thousands of people.”

Rahul Dholakia, whose film Raees also faced protests in 2017 for casting a Pakistani actress in it, almost harps in the same tune. The success of a film does make the future of a significant number of the crews who work from behind the screen. A Bollywood film, unlike a poem, is art that is primarily a commodity and meant to make business. That is why, perhaps, Aamir Khan has to make a plea to the audience not to boycott his films. This seems to be almost a move like Maniratnam’s team meeting Bal Thackeray in the 1990s. Not to boycott a film since it is a ‘collective art’ might be a good logic to support Bollywood and save it from further loss particularly when the epidemic has not yet stopped causing havoc to the country’s economy but such a logic is ideologically flawed as it fails to protect and uphold an Indian citizen’s rights to free thought and speech. It also raises the question whether we should at all judge art on the basis of an artist’s personal life, beliefs and ideologies. What about Picasso’s paintings or Neruda’s poems, then?

What, however, is the most unfortunate part of this whole campaign is the way some have given support to the boycott of Laal Singh Chaddha by dropping the name of Gandhi. To give support to the protesters, Gandhi’s call to boycott foreign goods in the non-cooperation movement has been cited. Surjeet Singh Rathore, the film producer and the leader of ‘Karni Sena,’ has even said, “Why should Indians watch his [Aamir Khan’s] film? In fact, producers should not invest money in such people, only then they will learn a lesson.” This intolerant remark clearly implies an economic revenge on Aamir Khan for voicing his anxieties over the secular character of the country seven years back.

Use of Gandhi in this context is dangerous for two reasons. It tries to mark someone like Aamir Khan out as a ‘foreigner’ (bideshi) and his film as a ‘foreign’ product. Such a stance results from the ideologue of the saffronites who considers all the Muslims as foreigners to this country. This is also one of the many instances of misappropriating Gandhi by the saffronites for their narrow political purpose. Never ever did Gandhi use boycott as a tool of passive resistance for any narrow communal purpose. Gandhi used satyagraha for the first time in India in 1917 when the peasants in Champaran in Bihar were forced to sell their crops at a fixed price to their largely British landlords. Non-cooperation as a form of protest was then used in Kheda satyagrahya which also resulted from the peasants’ demands for relief from taxes when they were badly affected by flood and famine. The famous Non-cooperation movement of the early 1920s was not, again, based on parochial or sectarian interests but was motivated by the larger mission of getting swaraj.

In all these events, Gandhi’s boycott did have economic implications but it was inseparable from his vision of the holistic growth of a country, a vision that was ‘inclusive’ and deeply connected with moral and spiritual development of both the nation and the individual. In fact, when in 1921, Indian National Congress endorsed Gandhi to launch a mass civil disobedience movement, it acknowledged that the movement would be based on “non-violent violation of unjust laws in obedience to the higher laws of morality”. Leo Tolstoy, who played a key role in the making of Gandhi, in his last letter to Gandhi wrote that to him “passive resistance” was “nothing else than the teaching of love uncorrupted by false interpretations”. Gandhi’s boycott, as a form of ‘passive resistance’ was based on non-violence and love and had no place for verbal abuse and hatred, the two heinous hands that hold the ‘#BoycottLaalSinghChaddha’ campaign tight.

Use of Gandhi to ideologically support the ‘#BoycottLaalSinghChaddha’ campaign by arguing that the protesters have the right to boycott a film that features someone whose statement once hurt the sentiments of a community, however, should not be seen as a stray incident. Saffronites have often misappropriated Indian heroes and legends for parochial purposes. They have even half-quoted Swami Vivekananda to prove the supremacy of Hindutva. Sane Indians, at least, should be aware of this strategic misappropriation of the legends of India by the saffronites and should condemn the politically motivated ‘cancel culture’ that is doing great damage not only to Bollywood but also to the multicultural fabric of the nation.

(Angshuman Kar, a Bengali poet and novelist, is Professor of English at the University of Burdwan, West Bengal. He was also Secretary of Sahitya Akademi, Eastern Region, and was twice a member of the Advisory Board [Bengali] of the Sahitya Akademi. He has 21 collections of poems, four novels, a collection of short stories, two books of prose, and two memoirs to his credit. Kar has received eight awards including the Krittibas Puroskar, Bangiyo Sahityo Parishad Puroskar and the Paschim Banga Bangla Akademi Puroskar. He has represented India at the SAARC Poetry Festival of Young Poets in 2008 and was also a member of the Indian delegation to Germany in 2014. He has read poems in the United States, Germany, Scotland and Bangladesh as well as in several poetry festivals across India. Kar is also a renowned translator and has edited Kalo Australiar Kabita [Poetry of Black Australia], an anthology of Aboriginal Australian poetry in Bengali translation and Simana Charie (Beyond the Borders), a volume of contemporary Assamese, Marathi, Gujarati, Malayalam and Telugu poetry in Bengali translation.)