The query: “At Auschwitz, tell me, where was God?” And the answer: “Where was man?”

—William Styron, Sophie’s Choice

In those few months of that year, I found myself in a wasteland, a dystopia almost. I walked into too many funerals. Of people who had suffered extreme violence. Delhi riots broke out on February 23, 2020, leaving 53 dead and nearly 600 injured. According to the police, 755 FIRs were lodged and 1,818 people arrested. The violence raged for four days. The majority of those who died were Muslims. Around 36. It was one of the worst religious conflicts in many years.

The recent communal violence in Nuh is just another in a series of many in the recent past that have a built-in hatred and paranoia against Muslims. The Rath Yatra in 1990 and the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992 that triggered religious riots in the country also caused a permanent fissure in the country’s social fabric and kind of condoned hate against Muslims. The hatred between communities was normalised and Islamophobia was nurtured and patronised even.

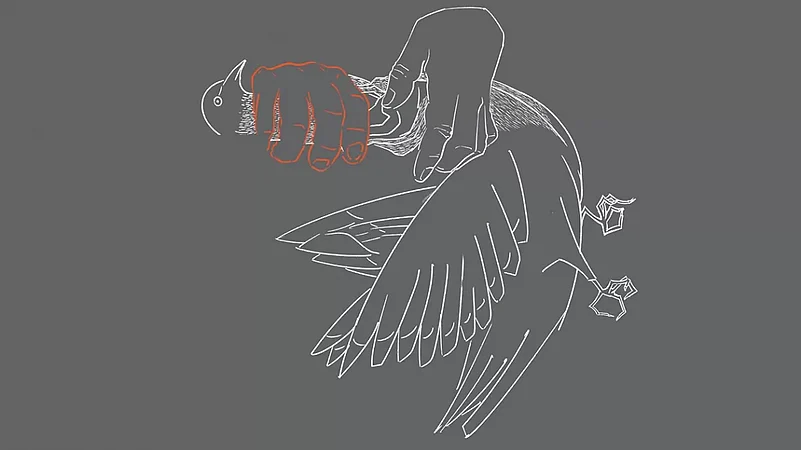

Our notebooks are archives of loss and violence, of sights and cries, of facts and details. We keep them close. We must. To understand and to reject, to remind and to remember. I remember that there was a lot of ash and broken glass everywhere in North East Delhi. Even pigeons and dogs looked coated in ash because so much was burnt down, so many murders had been committed and so many people lost their homes and hopes. I remember a story I had read in a newspaper then. A story about men wringing the necks of pigeons a Muslim man had kept in Shiv Vihar after they burnt down his home. It was a strange time.

Cities are divided, categorised in neighbourhoods to show status—upscale, middle-class, low-income, poor, Muslim and Hindu, Valmiki and Brahmin, etc. It hadn’t taken too long to get to the crime scene, to the heart of darkness. Division bells ring regularly now. Outside and inside. About 30 minutes from South Delhi. I remember seeing burnt cars, a smashed skull and a wounded body in a room, blackened walls and a lot of smoke.

Bound by the Yamuna on the West and Uttar Pradesh’s Ghaziabad on the East, Northeast Delhi is India’s most densely-populated district, and also one of its poorest. According to the 2011 Census, it has the highest Muslim population and the lowest literacy levels.

The origins of the riots lay in the peaceful sit-in protest by the women in New Seelampur demanding the revocation of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC). On February 23, 2020, the women here decided to march to Jaffrabad station and block the road below the metro line which connects to Maujpur and Yamuna Vihar. They had wanted to do a candle march. More women joined in from Welcome Colony, Janata Colony, Gokulpuri, Maujpur-Badarpur, and Shiv Vihar. Police arrived promptly to disperse the protest.

On February 23, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader Kapil Mishra demanded the women leave or be forcefully removed. He gave the Delhi Police a three-day “ultimatum” to clear them. In the days that followed, there were many funerals. In a room in Gulli No. 37 of Jaffrabad, Mohd. Irfan’s body lay wrapped in white. He had gone to get milk for his two children at night in New Usmanpur after Ajit Doval’s visit and the claims by the numerous media that the situation had become “normal.” He was killed by a mob just 300 metres from his house. His skull had deep gashes. Mohd. Irfan used to stitch bags in a manufacturing unit and was only 27. I remember reading that a man’s leg was given to his relatives for burial.

In Gulli No. 4 in Mustafabad, Aqil Ahmed, 40, was killed on the same evening as Irfan while he was on his way back from his in-laws’ place in nearby Loni. The body of the car washer lay in an open coffin. I recognised him. He used to work at the Khan Market parking lot. He was one of the many nameless people we meet every day but never know who they are. And then one day, you walk into their funeral.

His family found his body among the ‘unknown’ corpses at the GTB Hospital after he had been missing for three days. He left behind a wife and two young children. He earned around Rs 7,000. I remember the wailing. It had seemed like it would wake up the dead.

History repeats, they say. Torched mosques, mass arrests, exodus of Muslims, brick-throwing mobs, the fear, the loss of hope, the inaction of institutions, the murders and the silence in its wake.

I think of Rukhsar whose wedding I had attended on March 3 at the Al Hind Hospital. They took shelter at the hospital on February 26 from Govind Vihar. Her cousin agreed to marry her on March 1 because her fiancé didn’t want to marry someone who had lost her home. People in the neighborhood collected some money to buy her a pair of earrings and anklets and some glass bangles. The doctor at the hospital gifted her a red wedding ensemble. The pink lehenga that she had got made for the wedding was in her house. She hoped they hadn’t burnt it.

In Shiv Vihar, in the two adjacent parking lots, 170 cars were burnt in the violence. The mazar or the shrine on the main road in Bhajanpura had been burnt. I remember the keeper of the shrine washing the soot off the walls, floors and the grilled gates a few days later.

In 2020, I had returned to my archives of Muzzaffarnagar riots of 2013. I re-read the story of Amroz, 20, who had been killed.

“When you lose a son, it is like losing your eyes, hands, heart …,” Khurshida Begum, his mother, had said. Eyes, hands, other parts of the bodies of the murdered had been dismembered. Was killing them not enough, she had asked.

Amroz, 20; Meharban, 21; and Ajmal, 22, were beaten to death in sugarcane fields on the border of Muhammadpur. A mob, allegedly of Jats, had raised the slogan “Pakistan ya Kabristan!”

In September 2013, riots broke out in Muzaffarnagar district after a Muslim youth was killed for allegedly stalking a Jat girl, and then two Jat men were lynched in retaliation. Riots ensued and many died.

Our notebooks are sacred. More than any other texts. They are our defences in case of legal action. They are also our resistance against Islamophobia and any “otherisation” because in those pages, there are stories of people who passed or survived, their traumas, their dreams, their realities. In these pages, we have recorded a bit of their lives and deaths. They didn’t deserve to be killed. The pigeons didn’t have to be killed like that just because they had belonged to a Muslim man. That story is a sad one.

We are witnessing a lot of this kind of violence. Our family WhatsApp groups are sites of such extreme hatred against Muslims. Our social circles are proof that we love to hate. Our media is another manifestation of this polarisation. People don’t deserve to be killed because of hate. Hindus, Muslims, Christians and others. They are us. I don’t want to remember sad stories anymore. In the hope we don’t add new notebooks tagged as “riots” to our shelves.