Sometimes I wonder how many words we have in Hindi for rain. Then I think in English and go back to my childhood. There is a whole kingdom of languages that creates a two-way passage between my heart and the rain, and my complicated relation with languages.

The best memory of rain is sitting on the window sill and watching the downpour while Begum Akhtar sang, Hum to samjhe thhe ki barsat me barsegi sharab/aayi barsat to barsat ne dil tod diya (Showers of wine, I did think, would come with rainy clime,/But alas when it did rain my heart broke one more time).

The sense of desolation, longing and heartbreak, fills the room and my heart. This feeling has remained like an aftertaste and strangely back then was without understanding the lazzat (relishing) of sharab, or the lutf (to enjoy the pleasures) of ishq or for that matter the way Begum Akhtar sounded as her voice broke over a syllable.

Hearing her sing, ai mohabbat, her voice is the train to the past. Every single time I board that train and get down in a time that shines dimly in the vapourised glow of reminiscence, my heart swells. The ghazal is not just a ghazal. It is a 360-degree slow moving kaleidoscope, the Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. Rain thus meant Begum Akhtar on a loop. I can now only visualise the downpour in Patna back then during the rainy season. The rain would pour down in sheets as if the clouds had parted without a pause. This would continue for hours, and at times days.

Ma would say with resignation, “It is that type of rain that goes on relentlessly in a monotone, without much variation or drama. This is not the huge nautanki barish that thunders and shows its jalwa, only to subside in an hour. No. This will go on and on.”

After a few days into the monsoons, all one could see were stretches of muddy water everywhere. The smell of damp hung heavy. Wet clothes strung on a makeshift clothesline in one of the rooms, flapped crazily. The white school dresses turned light blue after dipped in Neel (Robin blue) and swayed in a frenzy as the fans were put on full speed to dry them fast.

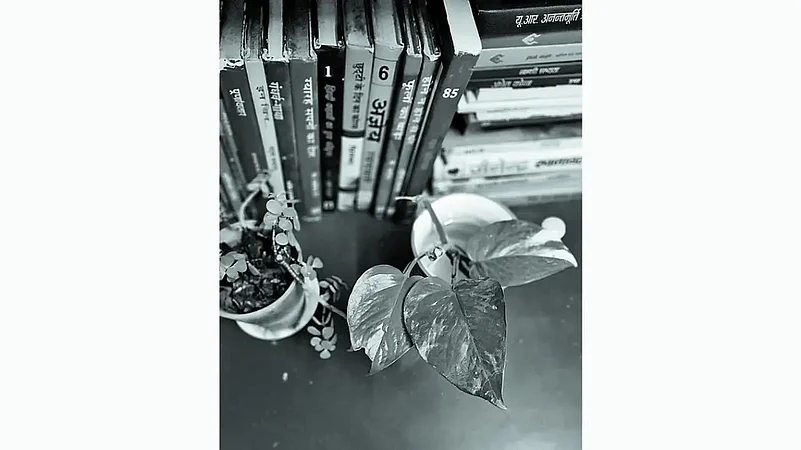

I snuggled in one of the easy chairs and read books as diverse as Emile Zola’s Nana, Phantom comics, Malory Towers, or even adult classics like Sons and Lovers, The Mayor of Casterbridge or The Razor’s Edge, again not understanding much, yet being carried along the magic of still-to-comprehend emotions in its entirety. Thomas Hardy, Somerset Maugham and William Faulkner got a special space in our house along with Phanishwar Nath Renu, Qurrut ul ain Haider and Mahadevi Verma.

Dark brown wooden boxes piled one upon another, held books and magazines all piling and spilling over. The Imprint and The Illustrated Weekly, Dharamyug and Dinaman and Woman & Home, stacked sloppily along with classics in Hindi and English. It rained incessantly for days on. The feeling of being dry was a feeling of comfort, a feeling of being home.

The children living in the out house were allowed to squelch in the mud in the backyard and sometimes they caught tiny garai fish that found its way in the tiny rivulets that connected the empty plots and backyards, mimicking rivers and luring fishes into a delusion. We would put the garai fish in a glass jar after begging ma to spare one from the kitchen. She would empty the masoor dal or kaala chana, and hand over the jar. Rain thus meant having a garai fish in the jar.

Rain meant the wet smell pervading the house and the damp smell of moist pages of the book being read. Sometimes, the green mildew growing at the edges stained our fingers and we shivered in disgust yet enthralled at the magic of being transported to the never-never land. Even now, reading a particular book takes me back to the window sill—the water stretching afar, the grey sky and the dripping umbrellas kept open in the verandah creating small puddles around which ants skirted in a row towards the pot with flowers blooming in abundance. I don’t remember those flowers at all. But I remember the river surely.

The river that became invisible. The river that vanished. All that remained was a bed of pebbles, large and small. The sal trees that stood on its banks were the witnesses. When the rains came after a particularly scorching and searing summer, the water fell torrentially in some mad frenzy. You could see nothing beyond. There was a sheet of solid water continuously sliding on the ground.

Then the river came alive. Its initial sweep was muddy, red, as if the earth bled. In two days, the river swelled and gurgled over bigger boulders. The water now dripped fat and heavy, slowly from the big wide sal leaves. You stood beneath the tree and the drops plopped on your head and your hair soon became wet. Your feet were already wet and the skin wrinkled like that of an old woman. Strange insects, centipedes and other scary creatures scurried out.

You had to be careful, not wear slippers but plastic shoes that bit at the instep. The yellow and pink cheap plastic raincoat was transparent. You wore it and felt mandrake, felt power flapping around you. Rain was thus flapping your arms through the rain coat, jumping in all the puddles, then being fed hot daal chawal and milk with Bournvita—a magic potion those days. It was much later that consumer gullibility was no longer prey to marketing manipulation and white lies. But then, those were ‘innocent’ days.

Rain no longer evokes such innocent nostalgia, and I wonder why. Now I dread and shiver if it rains. The long traffic jams, the water-clogged roads, the stalled cars... I live in an apartment and thus am saved from all wriggly creatures that invade the house each rainy season.

I constantly recommend friends to read Chasing the Monsoon and recall again and again how Alexander Frater even found beauty in the rain-swamped Dharavi. Did he have the same gaze that we had when we were young, when wading through dirty knee-deep water in narrow alleyways made us feel adventure, made us feel, ‘oh this is the sea’—the never then seen sea. It was about doing something out of the routine and feeling the exhilaration of that misadventure.

Now that I am older, the ecstasy of rain is gone. Yet on one of those rare occasions when it rains, I become a child. I walk out and am immediately drenched. My glasses fog and my hair hangs like rats’ tails. I kick the water out of puddles, and I am young again.

I remember an incident, a few years ago, while vacationing in Prague. We had just finished watching an opera by Dvorak at the magnificently grand Prague State Opera near Wenceslas Square, and were getting out. It had begun to drizzle, but not the kind of downpour we experience in India. Nevertheless, we stood waiting as so many others, crowding in the porch shelter. Suddenly there was the sound of a chant, Hare Krishna, Hare Rama. We were awestruck. It was a motley group of ISKCON followers chanting and dancing merrily in the rain. After Dvorak, it was the ecstatic seeking of Krishna, my favourite god after Shiva.

The ISKCON followers wore thin mulmul dhoti and kurta, sooti sari and blouse. They beat cymbals and mridang, made a loose circle and danced with sublime rapture. For about five minutes, the foreign air echoed with the Krishna chant. They danced in merriment, in ecstasy and came towards me smiling with warmth. Their rain-drenched faces opened up like a sunflower. They were mostly east European, and yet they came to me drawn by the common chord of India. I laughed. There was a golden glow in the air. Rain soaked glow. I stepped out, laughing turning my face upwards towards the sky.

It was all for a mere five minutes. The drizzle weakened and the group moved on till their chant grew faint. While remembering them, I can feel the rain on my face. Is my face then a sunflower too, opening up to the rain drops? I want to be like them in the rain. But those days are no more. It doesn’t rain like that anymore. My heart is no longer that heart anymore. I ransack my vocabulary and fetch words that will take me to the window sill. The little awkward 12-year-old, knees drawn up, looking at the rain with enchantment.

(Pratyaksha Sinha is the author of 11 books and a painter. Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print edition as "It Doesn’t Rain Like That Anymore")