It was 2021. For Janavi, a trans woman in Karnataka, the year came with hope and yearning. She applied for a position in the Karnataka police department. It was the first notification in the state that allowed transgender persons to apply for a government job. Janavi passed the physical endurance test—running, long jump and shot put—along with the written examination and was hopeful of getting through. But when the provisional list was put up, her name wasn’t there. “I was told that I was not physically fit enough for the job,” Janavi says.

Karnataka was lauded nationwide for being the first state in India to horizontally reserve jobs in public employment in favour of transgender persons in 2021. The feat came after countless requests, protests and visits to the court by transgender activists and their advocates. Sangama was one such non-governmental organisation, whose advocacy efforts resulted in an amendment to recruitment rules in May 2021 that granted one per cent reservation to transgender persons in the merit category, Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe and backward classes categories.

Why then wasn’t Janavi granted the benefits of this reservation?

“They said only trans men are allowed to apply for the post,” she says. Janavi was born male, and then transitioned to a female. “So why didn’t they tell me that when I came in for the other tests? They claimed that I couldn’t run with a battalion, and I was not physically fit enough,” she says.

***

A framed picture of BR Ambedkar and one of Mahatma Gandhi were comfortably placed next to each other at the head office of Sangama in Bengaluru. Hardly seven-eight members occupied the small, yet significant space nestled in between residential buildings upon a visit around mid-afternoon. “Sangama for us means social change,” says Nisha Gulur, who identifies as a trans person and is also the programme manager at Sangama.

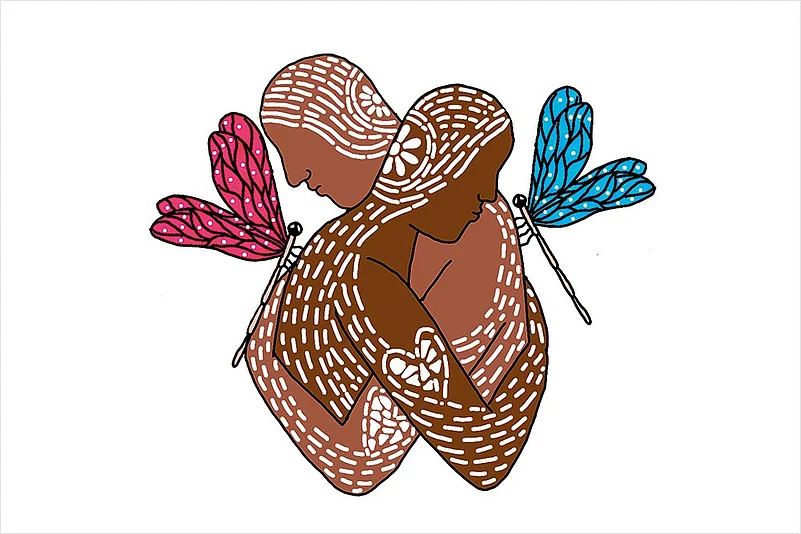

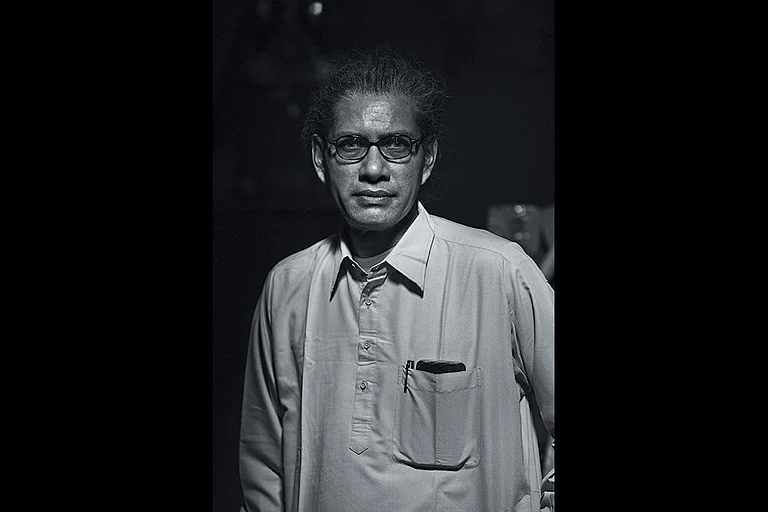

Founded in 1999 by Manohar Elavarthi as a centre that provided counselling services to sexual minorities and research material to scholars of LGBT issues, the organisation, over the years, has hosted discussions with social activists, provided HIV/AIDS information and awareness, and supported the rights of transgender people by organising rallies and marches. It now functions as a safe space for LGBTQIA+ individuals in Karnataka.

Gulur is busy making arrangements for a get-together for the community over the weekend. “Nothing too hectic … we are just going to dance and sing in a park,” she says.

Gulur was the petitioner who fought on behalf of Sangama in the Karnataka High Court. In her petition in 2021, she sought enforcement of fundamental rights by making a separate category available for transgender candidates to apply for jobs and to frame a scheme for reservation for the transgender community in recruitment. But three years since the reservation policy was notified, a majority of trans persons still struggle to apply for or secure these jobs and have little hope with unfulfilled promises.

Why Horizontal Reservation?

In the words of the architect of India’s constitution B R Ambedkar, reservation represents “protection against the aggressive communalism of the governing class, which wants to dominate the servile class in all fields of life.” Walking on similar lines, the Supreme Court delivered a landmark National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) judgement in 2014 that officially affirmed the fundamental rights of transgender persons—including their right to self-identify their gender and not face any discrimination as a result of that. The court also recognised that the transgender community is socially and educationally disadvantaged as a result of systemic discrimination and issued a slew of directions aimed at securing their rights and dignity.

The Supreme Court delivered a landmark National Legal Services Authority judgement in 2014 that officially affirmed the fundamental rights of transgender persons.

But when the idea of reservation for trans persons was first mooted, several state and central governments clubbed all transgender persons as a single homogenous unit, “backward class”, under the OBC category in a bid to confer to them the benefit of reservation—in sheer disregard of the intersectional identities of a transgender person, activists say.

Reiterating this, authors Prakhar Raghuvanshi and Sandhya Swaminathan wrote in 2022 that in such cases, transgender persons are made to compete with cisgender persons falling under the OBC category, despite the two having different social identities that form the basis for affirmative action. Secondly, transgender persons belonging to different castes (both upper and lower) are placed on the same pedestal. Third, transgender persons belonging to SC/STs would have to opt between SC/ST and OBC reservation. “While the former might be an obvious choice resulting in better benefits, it would be rooted in caste identity and entirely disregard gender identity,” they wrote.

A 25-year-old trans woman’s story from Delhi bears witness to the consequences of lack of horizontal reservation for the community. Aspiring to become a doctor, she diligently prepared for and wrote entrance exams seeking admission into AIIMS. Despite securing an all-India rank of 11 in the entrance exam, she was denied a seat at the well-known institute because of the six seats available, all went to cis-gender persons.

Hence, the Karnataka High Court’s judgement in 2021, providing one per cent horizontal reservation to the community, opened the doors for trans persons in the state and set an example for other states to be followed, Gulur says. As of 2024, Karnataka is still the only state to achieve this feat.

But Where Does It Stand Now?

There are many like Janvi, who welcome the reservation but are unable to avail it, says Uma, a trans woman from Bengaluru. “Many of us face documentation problems. We ran away from our homes, so we might not have a ration card or Aadhaar card with our preferred name and gender. So how will we apply for these schemes?” she asks.

Statistics show that most forms of data collection in the country have been sex-focused and not gender-focused, according to a report by the Centre for Internet and Society. “This shift in focus to data has led to further exclusion of already disenfranchised groups, including the transgender community,” the report stated.

For example, in November 2022, three transgender persons created history in Karnataka by becoming the first from the queer community to get recruited as government schoolteachers. However, they haven’t been able to begin working due to the vagaries of public sector employment.

Firstly, they (the teachers) were asked to provide details of their bank accounts—but with the same name as that which is mentioned in their educational documents. “Many of us have our dead names in those education certificates. How can we open our bank accounts in that name?” Uma asks. Dead name here refers to the birth name of a transgender person who has changed their name as part of their gender transition. Then they were asked to provide details of their ‘family tree’. “For many of us, the community is our family now. Not the people who share our blood,” adds Uma, who is also the executive director of Jeeva, a Bengaluru-based LGBTQIA+ advocacy group.

Trans activists are careful to point out that mere inclusion of a third box on government forms does not solve the problem. And in some cases, this third box too isn’t present—despite guidelines from the Karnataka High Court. Upon checking the websites of several government departments, Outlook found that many of their application forms still only had two options for gender—male and female.

Schemes for Transgender Voters

Ahead of the assembly elections in Karnataka last year, 41,312 transgender persons had registered to vote, according to the Election Commission of India—one of the highest numbers of trans voters reported by a state. The Congress’ success in that election was largely attributed towards the announcement of policies for trans persons and women, among others. But, over a year after the state government came to power, trans activists claim that these promises have only remained on paper.

One such scheme, Shakti, had promised free travel to all women and transgender persons throughout the state in government-run buses. But there are many trans persons in the community who haven’t undergone castration but still identify as a trans woman, Gulur points out. “Neither the bus conductors nor the government is sensitised on the diversity of the trans community and different identities under its umbrella,” she says. They have to undergo ridicule and humiliation due to lack of awareness on the part of the bus conductors, she adds.

Similarly, the benefits of the Gruha Lakshmi scheme, which offers financial assistance to women and trans women from low-income families, haven’t trickled down to the majority of the trans community, activists say. To avail the scheme, a trans woman must upload their ration card through a government portal. But till now, Uma says, the website doesn’t have a category other than male and female. “We keep following up with the Women and Child Development officials, but haven’t received a favourable response yet,” Uma says.

***

Back at Sangama, Gulur and team are preparing for their next meeting with Chief Minister Siddaramaiah. Despite elaborate plans, funds and policies penned down in thick manifestos, Gulur and other trans activists say a lot of work still has to be done on the ground to make these benefits accessible to the community.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(This appeared in the print as 'An On-Paper Policy?')