Sitting outside his prefabricated shed at the Vasu migrant camp in south Kashmir’s Kulgam district, Jatinder Raina, a 65-year-old retired electrician, wants the world to know the story of Sulla, an illiterate orphan who had four kanals of land to his name.

Raina says Sulla—short for Mohammad Sultan—used to work at the house of a Pandit family in his village in north Kashmir’s Langate. They treated him well and he trusted them. Eventually, he decided to transfer all the land he held to the Pandit family, deciding that his benefactors would be his ideal heirs.

“It was the day of Shiv Ratri or Hayrath in 1990. The Pandit family had sent Sulla to deliver walnuts to another Pandit house,” says Raina. Distributing dry walnuts among friends and relatives after puja is a local Hindu custom. “But,” Raina says, “a local tailor stopped Sulla, grabbed the walnuts, threw them to the ground and ridiculed Sulla for carrying out errands for Pandits.” The incident soon blew up into a fight between the tailor and other Muslim villagers, which Raina swears to have witnessed. In hindsight, Raina recalls this incident as an indication of the times ahead. “It made me realise that the situation was fast changing.”

What made the tailor confront Sulla over an errand the latter had been running for years? Why had he not done this before? Was the audacity of throwing the walnuts on the road a result of the new reality that had emboldened him to be communal or violent? Why then did the other Muslim villagers not support the tailor? Would the villagers have stood up for Sulla if the tailor had held a gun in his hand? Did they stand by Sulla the person or the idea that you could not discriminate—at least not so violently and blatantly—against a shared existence, of which Sulla was an unusual example?

Muhammad Farooq Wani, 71, was one among several survivors of the Gaw Kadal massacre. On January 21, 1990, when he was an assistant executive engineer with the Public Health Engineering department, he was on his way to collect curfew passes, when, nearing Gaw Kadal bridge, he saw a CRPF patrol open fire on protesters. There were bodies strewn everywhere, with blood flowing on the streets. Wani was also fired upon but miraculously survived. He says the situation changed dramatically after the 1987 assembly elections. A resident of Maisuma area of Lal Chowk, Wani was a student of Tyndale-Biscoe School and passed the matric examination in 1967. Most students in the school were KPs. Wani says he has excellent relations with KPs. “We belong to the same cultural ethos and would visit each other’s homes. Some of my best friends are KPs,” he says. He believes it was widespread fear that prompted KPs to flee the Valley.

ALSO READ: Routes Of Grief: Two Translations

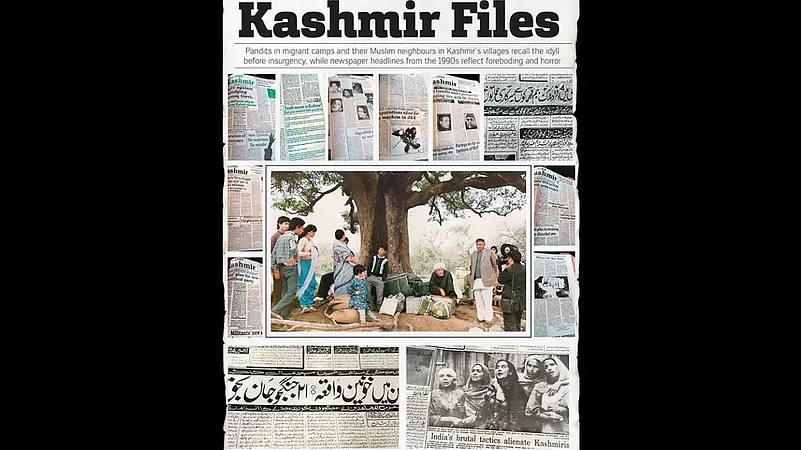

A cursory look at newspaper headlines from 1989-90 bears out Raina’s bewilderment at the change and its speed. A March 1989 report in Greater Kashmir—then a weekly—presents a picture of the Valley that is fast moving towards full-blown insurgency. It says on March 14, there was shelling on a house at Hari Singh High Street in Lal Chowk, in which three persons were wounded. The same day, the paper reports that a powerful explosion inside an eatery in Maharaj Bazar left seven people wounded. On March 19, 1989, the entire Lal Chowk and its surrounding areas were hit by rockets, damaging two shops and a building. The newspaper also reported a powerful explosion in Beerwah town in Budgam district that caused damage to the local higher secondary school, especially its science laboratory. Another headline reads: “Bomb blasts and bumper tourist season—the two can’t go together”.

If 1989 was the year of bombs and tourists, 1990 was the opposite. There were no tourists, only killings, bombs and demonstrations.

ALSO READ: Kashmir: Of ‘Stories’ And Friends

Headlines from December 1990 of Srinagar Times, a leading Urdu daily of the Valley, shows the scale of violence in the Valley and the sudden emergence of several militant groups. Sample these headlines and the banality of life they report: “Jammu Kashmir Mujahideen Islam warns jungle smugglers”, “Al-Mustafa Liberation Front appeals for unity”, “Yalgari Haider owns responsibility for militant attack”, “Hizb-ul Mujahideen expresses concern over felling of chinar trees”, “Hizb-ul Mujahideen warns against occupying vacant Kashmiri Pandit houses”, “Rocket fired at Barbar Shah”, “Crackdown in Nowhatta”, etc.

In its April 8, 1989, edition, the newspaper covers the death of separatist leader Shabir Ahmad Shah’s father G.M. Shah in police custody. The headline reads: “Shah’s death, sabotage or murder?”

ALSO READ: The ‘Homeland’ Dream Of Kashmiri Pandits

In his village in Langate, says Raina, communal harmony or peaceful coexistence wasn’t something for which you had to make an effort. It was there as a part of life, not consciously overbearing, yet imminent enough to be minded. “There was no inter-religious marriage between KPs and Muslims. Both communities knew it was against our ethos and culture,” says Raina. “When I got married, we had a feast for our Muslim friends. My wife’s family sacrificed two lambs for their Muslim neighbours.” Nothing extraordinary for life in the village. Raina, who lived with his father and three brothers, gives other examples of close relations between neighbours, regardless of faith. “In our house, we had a TV set. Our neighbour, Haji Sahab, would regularly visit our house at 8 pm to watch Pakistani serials,” he says, laughing.

But then, as Raina had feared after the incident with Sulla, things began to change rapidly and in ways no one had anticipated. “One day in 1990, at Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS), where I worked as an electrician, a young boy approached me and asked, “What time is it now?” Now, days ago, militants had instructed people to adjust their watches to Pakistan Standard Time (PST). So I knew why he was asking the question. When I looked at my watch and told him the PST time, he left.”

In another incident, Raina says security forces had killed about 10 people after a demonstration in Handwara. Enraged, some protesters had stopped outside his house and started shouting slogans. “Terrified, we kept asking ourselves why they had stopped outside our house.”

He also recalls bearing witness to the widespread normalisation of violence inflicted on Kashmiri Muslims. Another day in 1990, while he was at SKIMS, Raina heard that some people had thrown stones at the Army in the Nowshera area of Srinagar. The security forces, he says, had fired on the protesters. “That day, around 8-10 people were killed. There was mayhem in SKIMS. Even known militants arrived at the institute, asking ambulance drivers to fetch bodies from Nowshera.”

The tension was building up day-by-day. Every small incident could lead to a large number of casualties. People were dying everywhere, for different reasons. It was during one of these days, while he was at work, Raina says a fellow employee called “Ganderbali” told him that KPs should leave the Valley. “His remark was more like a threat,” Raina recalls. “I went home. There, I saw my brother, who was a teacher, writing some bills for our Muslim neighbour.” The threat at his workplace catalysed his fears. He felt an urgency to leave so that he and his family could survive. “The next day, we locked our house and handed over the keys to our neighbour Haji Sahab and left for Jammu. It was in May 1990.” He says no KP was killed in their area before or after the migration. He could have been the first.

ALSO READ: Loss And Longing In Kashmir

Sometime later in Jammu, where he lived with his family as a refugee in one of the many camps, he heard that two KP employees of SKIMS—Ratan Lal of Anantnag and Surinder of Ganderbal—had been brutally killed by militants, their bodies thrown in an open field outside the hospital.

Raina says his house was burnt down after they had left. Some of their land has also been encroached upon. He has submitted papers for its retrieval. “Some land I sold, some has been encroached upon,” he adds. What happened to Haji Sahab? “He died some years after we migrated. Our keys remained with him till his death.”

Raina returned to Kashmir in 1996—six years after he felt threatened by a co-worker to leave—as an advisor of a Pandit collective called All Kashmir Migrant Coordination Committee. In the Valley, they toured all districts and even met separatist leaders Yasin Malik, Syed Ali Shah Geelani, Shabir Ahmad Shah, Mirwaiz Umar Farooq and others. Recalling a meeting with Mirwaiz, Raina says, “We told him that the biggest blunder you did was forcing KPs out of the Valley. We told him that in these turbulent times, Pandits would have shown you the way out.”

ALSO READ: Kashmir: The Political Capital Of Pain

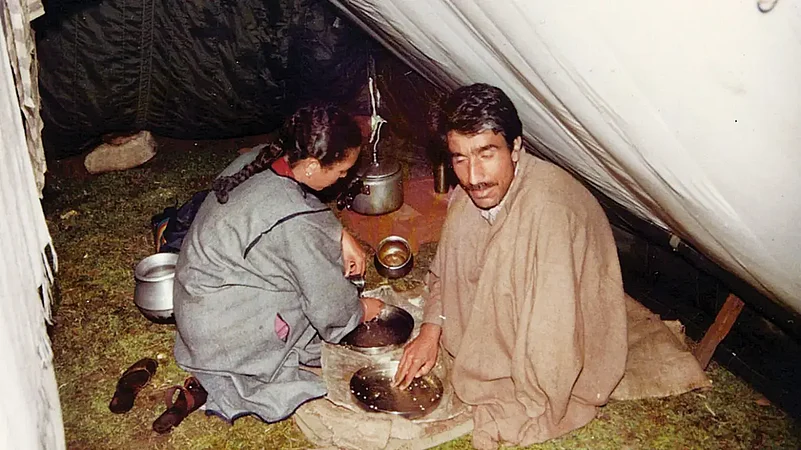

Mohan Lal, 77, gets emotional when he talks about life in his village in 1980s Kashmir. Sitting on a wooden bench in front of a grocery shop at the Vasu migrant camp in Kulgam district of south Kashmir, he says, “Those good times will not return to Kashmir.” The camp is just a few kilometres from his ancestral village Gund Jehangir.

“You don’t know what life we lived in our village. When I got married, the whole village was invited and we all had a great feast,” he says, preferring to speak in Kashmiri. “There were around 40 households in our village, 12 of which were KPs. We lived together, sharing our joys and sorrows,” he recalls. There is no trace of anger in Mohan Lal’s voice, as he keeps invoking God throughout the conversation. “Apuz kyzi wanav, khudayas Chu jawab deun (why should I lie, I have to answer to God),” he says, raising his hand toward the sky.

ALSO READ: Kashmir: Requiem For A Dream

“All my friends were Muslims. At times, we would sleep in the same room. We would visit each other’s houses. We would play and work together,” he says, taking a pause. “Then a tsunami came in 1990 and drowned all of us, Pandits and Muslims, in it.”

He says one day in May 1990, he was returning home from work when he heard that all Pandits were leaving the Valley. “It was sudden. There were no protests in our village; there was no sloganeering. There was a rumour that Pandits are leaving. I took my wife and four children—three daughters and a son—and left for Jammu. I handed over the keys of my house to my neighbour Mohideen. We lived a miserable life in a tin shed in the scorching heat of Udhampur for almost five years,” he says. “Years later, my Muslim friends told me my house was burnt down after we had left.”

ALSO READ: In Search Of Home In Pandit Houses

But why didn’t Mohideen try to save the house? “What could that poor man have done?” Mohan Lal says angrily. “In our village, 15 people, all Muslims, were killed over the years. How could he have saved my house in those tumultuous times,” he says. “Mohideen died a few years later,” Mohan Lal says, with sadness in his voice.

Thirty years down the line, Mohan Lal remembers friends from childhood. Master Ghulam Nabi, Ghulam Hassan Bhat, and Abdus Salam Lone. They came to Jammu to meet him a few years after the Lals had migrated. Since then they have remained in touch. These days, Mohan Lal visits his village and his friends visit him in the migrant camp.

Newspaper headings have not changed since 1989. In the killing fields of Kashmir, the leading news of the Valley’s largest circulating daily Greater Kashmir on Sunday reads: “Militants kill two brothers”. Another headline says: “Thousands visit tulip garden”.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Kashmir Files")

ALSO READ

Naseer Ganai in Srinagar and Kulgam

.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=376&dpr=2.0)