This story was published as part of Outlook Magazine's 'Kashmir Memory Files' issue, dated April 11, 2022.This appeared in print as Of ‘Stories’ And Friends"

Recently, I was part of a panel discussion titled Beginnings and Endings in the context of writing a novel. At the end of the session, a member of the audience stood up with a question. As per the man’s own confession, he has been asking this question to every writer of fiction that he comes across. Thousands of books are written every year, he asked, and thousands, if not more, are read every year; but to what end? In a world full of strife and pain, do ‘stories’ ever change anything?

The answers from the dais — some convincing, some not so convincing — included various iterations of art for art’s sake, catharsis, escapism, self-expression, vent to the imagination, the usual suspects, that is. The man with the question sat back in his chair. He had nothing more to say. For all practical purposes, the question was answered. However, I was perturbed. It was a sort of irritation that you feel when you cheat someone without meaning to do it. The purpose of art is a question as old as art itself, as are the answers. Answers that may leave you unconvinced but never resentful like the answers from that dais had left me. What did I miss?

ALSO READ: Kashmir: This Isn’t A Postcard Series

Back at the hotel, news arrived from home — from Kashmir — that an encounter had started at a village nearby. ‘Khudaya karei sahlie (God will be merciful)’, my family says over the phone. I could see them already huddled in a room that is presumed to be the safest in our house — one with the thickest walls and the smallest windows. They would have a long, terrifying night ahead. A night full of a hundred metallic wolves howling for blood, and shooting bullet after bullet. At home, nobody would dare to sleep but everyone would pretend to. Lights turned off, words would be rationed and everybody would be praying that no baby cries tonight. All this while, miles away, I am at a fancy festival discussing art and literature; listening to people about what they think of my novel and what I think of theirs; dissecting the stories that we have put out for people to read.

Would any of these novels mean anything to my family tonight? Would any of these novels mean anything to the family whose house would be no more than a pile of rubble and ash by the end of the night? Would any of these novels mean anything to the one who must be getting ready to bury his/her dear ones? Suddenly, the man from the audience was standing before me asking his question. “In a world full of strife and pain, do ‘stories’ ever change anything?” This time I could hear his question loud and clear.

It was the photographs where I saw my father’s Pandit friend for the first time — at college, in shikaras on the Dal lake, under blossoming almond trees, at my father’s wedding. My father had a story for each of the photograph, sometimes two. And then, on my way to school, there were other stories about the Pandit friend. Here was the tea stall where they used to while away their time; there was the alley that used to be a shortcut to the Pandit friend’s house, which was the perfect getaway for bunking classes; this was the electric pole into which they had rammed their bike while trying to recreate a Bollywood stunt; that was the playground where they were defeated in their greatest cricket final. The Pandit friend had left the Valley in that infamous winter of the ’90s, but the stories didn’t stop there as father visited his friend in Jammu every now and then. But there was nothing cheerful about this lot of stories. I added bitterness borne out of suffering to the man whose flesh and bones I had pieced together from my father’s stories. Yet that was not how it was when I met that man in person for the first time.

ALSO READ: Routes Of Grief: Two Translations

On a pleasant spring afternoon, I came back home to my father sitting with his Pandit friend who had a cigarette dangling between his fingers and an irresistible smile hanging from the corners of his lips. It was the late ’90s, and the Pandit friend had decided to visit the Valley for the first time since the Pandit exodus. Over the course of the next few days, as this friend of my father busted almost every myth that my father had built around him, I could not help it but like him as much as I had liked him in the stories of my father. He was as charming and as adorable as I had made him up in my head. What was even more impressive was the absence of bitterness that I had ascribed to him owing to my father’s Jammu stories. He had reason enough to be as vindictive as he could be. Nobody would grudge him for that. But, instead, he had chosen to be this man full of warmth and love that he appeared no less than a saint for me. You could tell he was grieving over what he had lost. One look at his eyes and you would come to know of such depths of pain that would never be fair as a share for anyone, living or dead. But the thing about this pain was that it did not make you angry or bitter. It just made you sad. So sad that it felt as if someone had just announced the end of the world and you had no one to hold your hand.

ALSO READ: The ‘Homeland’ Dream Of Kashmiri Pandits

There were many more visits after that. Every time the Pandit friend came back to the Valley, he made it a point to visit us. I began to think of him as an uncle who lived in a far-off place.

I had heard it before, in so many WhatsApp forwards and so many social media posts. I understood it. Mind you, I did not agree with it, I just understood it.

And, then, I came across his Facebook profile. As I scrolled down, vitriolic post after post appeared on my screen. For a moment, I tried to find an excuse — maybe it wasn’t him, somebody else running a profile in his name and with his DP (Display Picture) — but there were details that I could not ignore. Things only he could have said, pictures that only he could have uploaded. Even if there was none of that, in my heart of hearts, I knew it was him. It could be nobody but him.

ALSO READ: Kashmir Files: Memories Of Another Day

The hate, the malice against my community — the Kashmiri Muslims — that these rants on his wall reeked of, was not something that appalled me. This hate, this malice against Kashmiri Muslims was not something new. I had heard it before, in so many WhatsApp forwards and so many social media posts. I understood it. Mind you, I did not agree with it, I just understood it. I knew where it came from. The late Agha Shahid Ali had said it so succinctly for all of us:

“You needed me. You needed to perfect me.

In your absence you polished me into the Enemy.

Your history gets into the way of my memory.

I am everything you lost. You can’t forgive me.

I am everything you lost. Your perfect Enemy.”

For every Kashmiri Pandit in exile, the Kashmiri Muslim was the perfect enemy. The wily, scheming, kohl-eyed, bearded, and gun-toting perfect enemy. Of course, this monolithic Kashmiri Muslim did not include the Kashmiri Muslims that they know personally just like the Pandit friend did not mean my father or me or my family when he referred to the Kashmir Muslim in his post. I was sure of that. As I was sure of the love and warmth that he had exuded every time he was at our house. There was not an iota of doubt about the genuineness of his emotion, and of his earnest feelings for my father and my father’s family. Did that make him a hypocrite then? A bigot? No. It just made him human for me. We all have our own little bigotries and personal hypocrisies. But it would be a travesty if that is all we are deemed to be. We are much more than our bundle of contradictions and much more than the sum total of our vices.

I had reconciled the seeming duality of my father’s friend and I believed my father, if he ever came to know about it, would too. But what about my children? Would their grandfather’s friend be no more than what he was on his Facebook wall? And, most terrifyingly, what about the children and grandchildren of the Pandit friend? Would my father, my children and I be no more to them than what we were on his Facebook wall? What made it possible for me to accept this Pandit friend’s duality? What could make it possible for the Pandit friend’s children to accept our duality?

Stories. Yes, ‘stories’ was the only answer. It was the stories of my father that circumvented time and space to make his Pandit friend reach out to me. It is stories that can make us reach out to the other and to the enemy. Stories are our chance to reclaim humanity. I fervently hope that someday I will run again into that gentleman from the audience who had asked me, “In a world full of strife and pain, do ‘stories’ ever change anything?” This time there will be no cheating. This time I have my answer ready.

This time I have a story to tell.

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

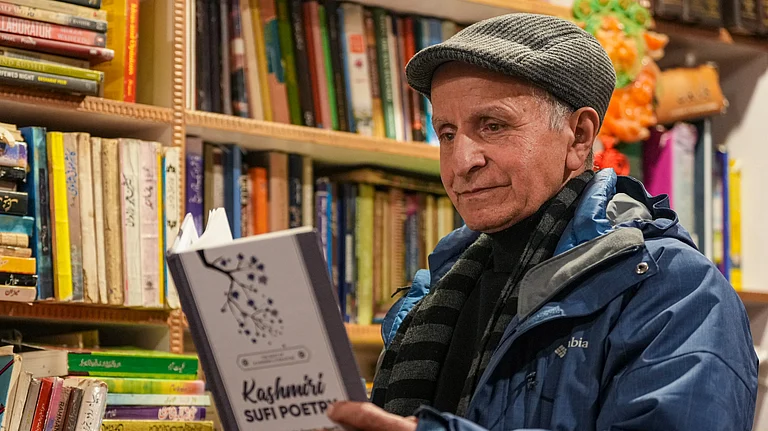

Shabir Ahmad Mir is the author of The Plague Upon Us

.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=376&dpr=2.0)