Political murders in Kerala have recently taken the centre stage in the national media. Your film Shantham, which won the national award for best film in 2000, is centered on political murders in the state. What got you to make a film on this subject back then?

I got the idea of the film, Shantham, when someone told me about a real-life incident. It was about a chance encounter of two mothers at the famous Guruvayur temple. One of them was the mother of a political murder victim in Kannur. The other one was the mother of the murderer. They came across each other at the pradakshina of the temple. It struck my mind immediately as the best expression of the vicious cycle of political violence in Kannur, where each party keeps a score card of the number of deaths from their side. The victim’s mother was there to pray for her deceased son. The perpetrator’s mother was there to pray for the life of her son who could be killed anytime in vengeance. This is the same expression we can see in Mahabharata when Kunti Devi and Gandhari, the mothers of Pandavas and Kauravas respectively, become shattered after seeing post-war Kurukshetra.

The film (starring Indian football legend I.M. Vijayan) is set in Thirunavaya, the venue of Mamankam, a medieval military and cultural festival, on the banks of River Nila. There are three temples of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva on three corners of the river bank representing srishti, stiti, samhara. The mother duo, who used to live as if they were members of the same family, arrives here. The victim’s mother comes along with his wife and son to pray for his soul. The perpetrator’s mother comes to the Shiva temple on the other side of the river to pray for the safety of her son. When they happen to meet, they curse each other, cry out loud and collapse. Meanwhile, the victim’s friends get ready to avenge the killing of their man. In the end, the victim’s mother and wife, along with a large group of women and children who appear on the screen from nowhere, march ahead and stop those men who were heading with swords held high in their hands. I wanted to end the film by showing the hands that stop these swords. When we were shooting the climax scene, a dragonfly came and stood on the tip of the sword. It wasn’t CGI, nor was it planned. It happened as if an invisible force was at work. So, I ended it there.

We tried our best to reach this film to a wider audience. We ran the first show of the film for free in Kannur, the epicenter of political violence, which was a first in the history of Malayalam cinema.

Seventeen years later, how is it different today?

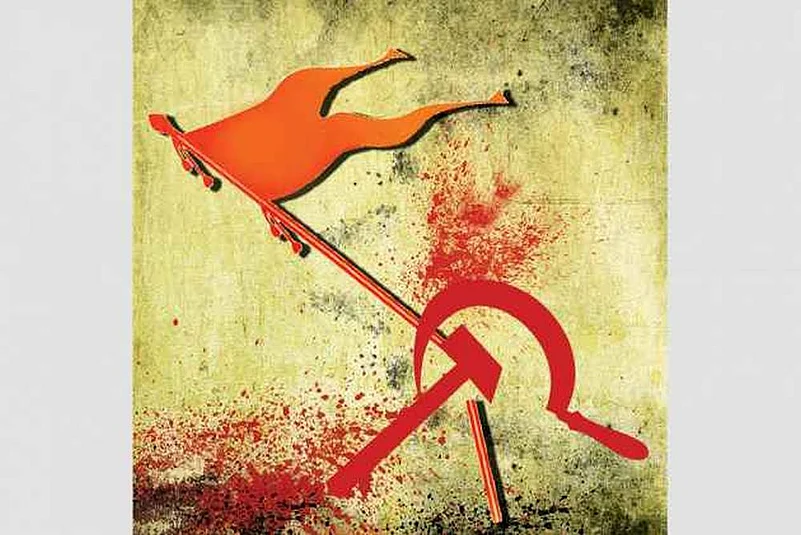

Earlier, we could allege that such vicious cycle of political violence was only seen in Kannur and adjacent areas. But, today it is spreading to other parts. Kannur had a history of feud and vengeance. But, when Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala’s capital) reports a political murder, it is a clear signal that we have to be more alert. We should be cautious not to let violence become normalised in our society. Earlier, violence used to be an act of vengeance by rivals. It was emotionally charged over the loss of their dear ones or over a political belief. But, today it is done by hired criminals. Today you can see that they are well planned criminal acts. It is time we raise an important question- who is benefitting from it and what are their goals?

The current debate on political murders in Kerala seems to be confined to the number of deaths on each side of the political spectrum. Do you think there is a need for a debate on humanitarian grounds?

The issue has to be seen from a third perspective. The victims’ wives, mothers and the children must be the dominant figures in this parallel narrative. Writers, artists and cultural activists must take a lead to bring in a new narrative. Currently, political parties are using violence for their show of strength and they are using it to nurture an element of fear for their growth and survival.

Could you please tell us briefly about the history and nature of this political violence?

As I said earlier, Thirunavaya, where Shantham film was shot, is historically significant as that was the venue of Mamankam in 18th century. The Valluvanadan king used to send suicide gangs (Chaver) to fight Samoothiri of Kozhikode. Even though they were sure of their defeat, these suicide gangs would observe fast ahead of the battle, bid farewell to their dear ones and walk to the nilapadu thara (the ceremonial stage) to fight until death. It was nothing but a sacrifice for their king. Traditionally, the people of this region are so sincere and committed to what/who they believe in. My last film, Veeram (a historical drama starring Kunal Kapur), also portrays some element of feud and violence. The film portrays chekavanmnar, the warriors of northern Malabar, who would also fight on behalf of their feudal lords. Fight was their immediate resort to settle even the minor disputes, may be in the name of a coconut tree that bend to someone else’s land.

What should be the way forward?

The respective political parties should take responsibility for every political murder in the state. There should be a new legislation to make parties and their leaders liable to every incidence of political violence. The leaders responsible should be punished. My son recently woke up on a fine morning and asked if it was a holiday. When I asked why he thought so, he cited the murder case of the previous day and said he had assumed that a hartal was declared on the day. I was quite shocked. It showed the normalization of our society’s violent attitude. Our children should not be allowed to get conditioned to violence.