It was sprung on us as the stuff of dreams—a free, borderless world, a knowledge utopia, a permanent democracy. All that slowly morphed into something grittier, something resembling the real world, replete with lawless zones where an average parent would dread finding their child. That said, the internet is pretty universal: it draws everyone in. (In 2016, an average Facebook user spent 50 minutes every day doing Zuck all.)

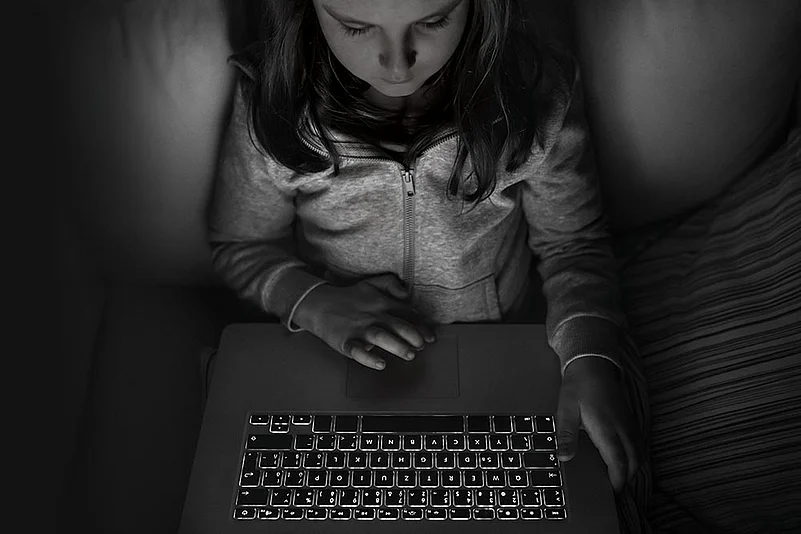

In internet time, 2016 was a long time ago. A decade is a century. In the noughties, teens were trying to figure how to write a testimonial for their partners on Orkut. Now, two-year-olds clap and giggle at the antics of Peppa Pig on Papa’s smartphone. It’s getting more than a little scary: children playing so near the open infobahns. Many countries have legislated on this. Now India is also trying to understand the core issue: when can children be let loose into the big, bad virtual world?

Towards the end of 2017, the Sri Krishna Committee on Data Protection, constituted to draft a framework for such a law, released a white paper with a chapter titled ‘Child’s Consent’. Here, the committee sought views on what a legislation should look like, how the appropriate age should be established and the nature of consent defined. ‘Consent’ is the key concept here: the word can generate no coherent sense when it comes to children, as is known in the field of sexuality. “Children represent a vulnerable group, which may benefit from receiving a heightened level of protection with respect to their personal information,” the paper says.

The only existing law applicable here is from 1872. The Indian Contract Act says any person can sign a contract after age 18—surely an outdated paradigm given that one out of three people on the internet are below that age. And even adults are fairly woolly about what a ‘contract’ with the likes of Google and FB entails.

So how vulnerable are children really on the internet? Santanu Mishra, co-founder of the Smile Foundation, cites Blue Whale and the recent spate of school murders to say the environment around us is “extremely precarious”. “The addiction to high-tech products has eroded the culture of deliberation and dialogue with parents, driving young minds towards low confidence, zero self-respect and an emotionless state,” he adds.

Over 1,540 cases of online child abuse were registered in India in 2013-15, according to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data. “With increasing online presence, and in the absence of information and lack of processes to ensure privacy, children are vulnerable to abuse and exploitation,” says a Save the Children spokesperson. Swarnima Bhargava, a clinical psychologist with Children First, says “vulnerability stands to grow”, partly due to “screen addiction”. Apar Gupta, an advocate who works on data privacy, also notes how children are now provided with devices from an early age—not “just as an educational tool, but also to socialise”, increasing vulnerability.

In its white paper, the committee asks which websites should comply with child protection if it comes into force. Some experts feel all websites should comply, and some have nuanced takes, but most insist on social networking websites doing so. “All social media sites should be included as well as popular search engines like Google,” says Swarnima.

While FB and Twitter have set age restrictions at 13 years for sign-ups, children are known to falsify their age and gain access. Apar Gupta believes the law should “spell out the criteria under which the regulator should act. One important criterion could be whether the website is aimed towards or allows children to use services by itself.” He feels there should also be criteria to see how certain websites do not fall under the ambit of such specific regulation.

There’s also data: a simple Google search on a child’s name will, in many instances, direct a user to details of all of his/her class-fellows. And of course, that brings on all dangers: from the merely unethical (targeted advertising) to the outright spooky (tracking and worse, grooming by paedophiles). The committee feels schools and the government should do much more here to ensure safety. Schools insist there is not much they can do. “From our side, we don’t want any child’s data made public,” says Tania Joshi, principal, The Indian School, New Delhi.

On the use of a child’s data for advertising and tracking purposes, most experts are unambiguous. “The practice of targeting children to turn them into avid consumers needs to be resisted as far as possible,” says Swarnima. Santanu Mishra says data gathered from children should “especially” not be used. Gupta cautions against the nature of algorithms on the internet itself, saying they “may lead to various forms of emotional manipulation.”

It all boils down, though, to the age at which a child may be permitted to venture out on the internet on its own. The white paper cites the norms in select countries abroad: in the US, COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) seeks to protect children’s privacy below 13; the EU’s GDPR sets it at 16, (EU nations can set their own, however); South Africa and Australia have it at 18. Experts we spoke to suggest the age may be lowered later as internet literacy goes up further, but they differ, of course, on the exact number.

Apar Gupta likens this to an extra-curricular activity like an outdoor field trip, where parental consent is necessary. “If we depart from the Contract Act (which stipulates an age of 18), the move should be well-reasoned,” he says. “I think 18 for consent may be a high threshold for online services and we should adopt 13 or 15 as the relevant age.”

Children’s organisations offer a note of caution, however. Save the Children believes the age should stand at 18, as per the Contract Act. Mishra of the Smile Foundation believes while a child between 14 and 16 years does have an “obscure understanding of good and bad,” a parent should supervise the decision-making until the child is 18.

And finally moving on to parents, experts feel they need to up their game and be more on guard in these times, and spending some time understanding the concept of consent themselves and what it can denote wouldn’t be a bad start. Bhargava says “consumer literacy needs to be spearheaded across society before we can expect consumers to make sophisticated decisions” of such a kind. Joshi mentions that her school invites cyber crime experts for computer literacy classes, also mentioning that usage is not at the level of the 9th standard students anymore, but “right now it is happening to class 3 level students”.

Gupta says consumer awareness and expertise—similar to checking for an ISI mark, for example—comes with time. He says regulators need to come up with clear rules and mentions the EU GDPR which “relies on consent not being a principle in isolation, but along with purpose limitation; it means whatever you are doing is done with the least amount of data possible and you should design privacy protection inherently in the architecture of technology apps.”

That would mean an application for net banking would thus not ask for permission to use the microphone on the device, for example. He says once features like purpose limitation, the necessity and proportionality of data-gathering, disclosure and accountability provisions, choosing to possibly opt out etc are drafted into the law, consumer demand will ensure that “more and more applications will come that address not only the regulations, but also consumer interest”.

That said, however, consumer literacy with respect to the internet still leaves much to be desired and parents must understand the nature of the beast they are dealing with. While data protection for everyone is something the powers that be are looking to address, there is a generation born in the digital age who aren’t migrants, and whose future needs require urgent attention.