The debate on personal law reforms and the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) goes back almost a century. It was hotly debated in the Constituent Assembly, which could not come to a conclusion. Finally, the Constitution came up with the following formulation through Article 44, “The state shall endeavour to secure a uniform civil code to all the citizens throughout the territory of India.”

Even the Supreme Court could not decide the matter which came before it repeatedly. It even expressed its frustration calling UCC a “dead letter”. The Court emphasised the need for Parliament to enact. But governments have come and gone without being able to clinch the issue. Even the BJP governments, which have ruled in several states, could not resolve the issue. Most significantly, even the Law Commission appointed by the current regime couldn’t resolve it. After extensive deliberations for over two years, it came to a momentous conclusion that UCC is “neither necessary nor desirable”.

Who raises the demand and why? It is the foot soldiers of the right wing, who want to keep the communal pot boiling; to create hatred; and, inter-communal polarisation. All in the name of integrity. I have asked many people why they want UCC. Their reply is overwhelmingly inspired by polygamy. How can we have two laws in the country for two communities, they would ask. Their concern for the subordinate status of Muslim women is touching, despite their proven credentials of Muslim phobia. Even an illiterate child on the street has heard of triple talaq, nikah halala!

The fact is that triple talaq was the most despicable practice practised by some illiterate Muslims. It’s good that the SC has declared it illegal. My question is: why was it not declared un-Islamic and illegal by the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB)?

Allah looks down upon every divorce. The Quran has clearly prescribed the procedure for divorce, should this become unavoidable. And it is very humane. Talaq could be given thrice, spaced by three menstrual cycles, to create scope for reconciliation, which was the recommended option. Some illiterate Muslims invented the abhorrent practice of instant triple talaq, in complete violation of the Quran. It would have been most appropriate if AIMPLB, and not the SC, had declared it illegal.

It’s worth pondering that a verbal talaq is much better than getting rid of an unwanted wife through criminal practices like bride burning. Fortunately, this despicable practice has now become near extinct.

Since the alleged Muslim polygamy is behind the demand for UCC, it is important to uncover the ignorance that prevails both among the Muslims and the Hindus. First, even the Muslims don’t know that Islam prefers monogamy. The Quran has only one verse on the subject, permitting it, but with two conditions—absolute equality between wives and marrying orphans/widows. (Surah AnNisa 4:3).

The other widespread belief is that Muslims are mostly polygamous. Hum paanch, hamare pachees (we 5, our 25) or hum chaar, hamare chalees (we 4, ours 40) is a slogan used even by senior right wing leaders. The facts are the opposite as pointed out by the Law Commission Report. It records that all communities have polygamy, but Muslims have the least—Tribals 15.25 per cent, Buddhists 9.7, Jains 6.72, Hindus 5.8 and Muslims 5.7. It’s a strange paradox that Muslims who are least polygamous are willing to die fighting for this right! And those who practise it more never tire of giving Muslims a bad name.

Even the SC has dealt with the subject and has the following important observation: “Clandestine bigamy among Hindus is worse than open polygamy among Muslims who are legally bound to treat them equally in maintenance and love.” The Supreme Court in the D Velusamy (2010) case denied maintenance to a second Hindu wife by holding her as “mistress” and “keep”. “Thus banning polygamy would simply have the equal effect of making a second Muslim wife a destitute and vulnerable as a second Hindu wife.” Lawyer activist Flavia Agnes observes, “The condition of Muslim women is not more deplorable than the condition of Hindu women.” “UCC is generally applied as a political tool against Islam and Muslims,” she adds.

There is no doubt about the backwardness of the Muslim community in general. Flavia, however, doesn’t believe Muslim personal law to be the cause of the backwardness of the Muslim community. She thinks UCC is just a political tool against Islam and Muslims by highlighting the issues of polygamy, gender equality and triple talaq.

Most of those who consider UCC a panacea for all ills in society are not even aware that UCC is not just about polygamy. It refers to laws pertaining to marriage, maintenance, divorce, adoption and inheritance. Sarid Naved, a law professional, goes to the extent of suggesting that Article 44 is not restricted to personal laws, but is a constitutional call for equality in all walks of life. He adds that Muslim personal laws have provided women a much fairer deal than traditional Hindu laws, but with Hindu Code reforms, culminating in the 2005 amendments to the Hindu Succession Act, they are a step behind in gender justice in terms of law of succession.

The Law Commission says that all communities have polygamy, but Muslims have the least.

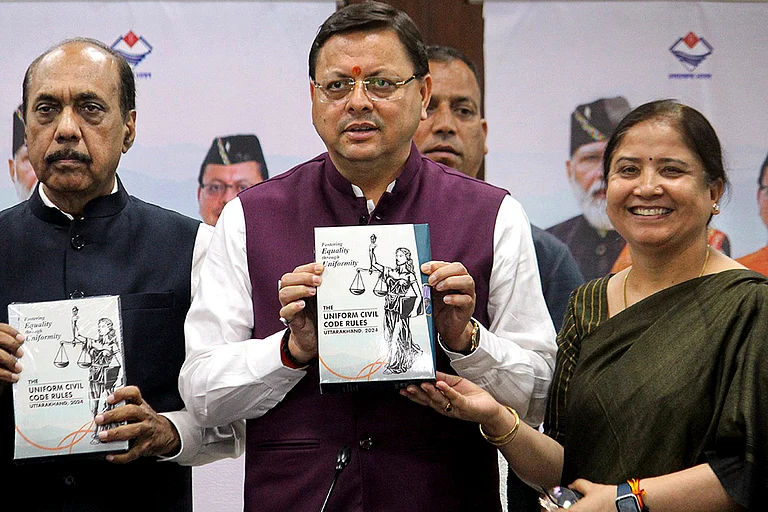

The supporters of UCC believe that personal laws based on religion are an affront to the nation’s unity and add that the UCC will ensure the integration of India by bringing different communities on a common platform. Several BJP ruled states, like Uttarakhand and Gujarat, have announced setting up committees to implement the UCC. UP, Himachal Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh have been repeatedly raking up the issue.

Critics who termed the code as anti-minority believe UCC goes against the values of unity in diversity prevalent in India. The UCC would affect their customs and religious practises.

In 2018, the Law Commission of India examined the issue at length receiving 75,378 representations. After the largest and widest deliberations ever, the Commission came to a startling conclusion that the “UCC is neither necessary nor desirable”, stating that the issue is vast and that its potential repercussions are untested in India. The panel said that the existence of difference does not imply discrimination, but is indicative of a robust democracy. The panel emphasised that, instead, there is a need to deal with laws that discriminate between men and women.

According to political scientist Asim Ali, framing of a UCC will open a Pandora’s box, with unintended consequences even for the country’s Hindu majority, which the BJP professes to represent. The UCC would disrupt the social life of Hindus as well as Muslims. He goes on to say that personal laws are free and extremely difficult to unify in a staggeringly diverse and vast country like India.

It’s important to know that there are different laws regarding property and inheritance rights not just for different religious communities, but for different states too. North-eastern states like Nagaland and Mizoram have their own personal laws that follow their customs and not religion. Goa, which has a common civil law since 1867, also has different rules for Catholics and other communities.

The sixth schedule of the Constitution of India provides certain protections to a number of states. While some tribal laws, in fact, protect matriarchal system of family organisations, some of these also preserve provisions which are not in the interest of women. There are further provisions that allow for the complete autonomy on matters of family law. These can also be adjudicated by the local panchayats, who too follow their own procedures. The Law Commission also said: “Cultural diversity cannot be compromised to the extent that our urge for uniformity itself becomes the reason for threat to the territorial integrity of the nation.”

While there is certainly a desire for change, there is also, equally, a need to acknowledge the hindrances to any endeavours to institute a UCC. The first foreseeable problem with feasibility is with respect to the sixth schedule of the Constitution. Article 371 (A) to (I) and the sixth schedule provide certain protections or rather exceptions to the state of Assam, Nagaland, Mizoram, Andhra Pradesh and Goa with respect to family law. It is also noteworthy that the code of criminal procedure (CrPC) 1973 is not applicable to the state of Nagaland and to the tribal areas.

How would a BJP government reconcile to a uniform law that allows marriages between religions, but with anti-conversion laws that it supports?

Many also argue that a uniform code may advance the cause of national integration. However, this may not necessarily be the case when cultural differences inform people’s identity and its preservation guarantees the territorial integrity of the nation. While tribal customs may not fit mainstream notions of morality, these are treated as common practices in those areas. Thus, secularism cannot be contradictory to plurality. It totally enjoys peaceful coexistence of cultural differences.

What principles do you apply–Hindu, Muslim or Christian? wonders Alok Prasanna Kumar, fellow at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Asim Ali points out to a political blowback. How would a BJP government reconcile uniform law that freely allows marriages between religions and communities with anti-conversion laws that it has enthusiastically supported to curb interfaith marriages.

The commission’s concern was to address discriminatory provisions under all family laws. The commission was of the view that “it is discrimination and not difference which lies at the root of inequality”. It suggested a range of amendments to existing family laws and codification of certain aspects of the laws so as to limit the ambiguity in interpretation and application of these personal laws.

In the absence of any consensus on UCC, the commission felt the best way forward may be to preserve the diversity of personal laws, but at the same time, ensure that personal laws do not contradict the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution of India. The commission added, it is desirable that all personal laws relating to matters of family must first be codified to the greatest extent possible, and the inequalities that have crept into codified law, should be remedied by amendments.

While the freedom of religion and right to not just practice, but propagate religion must be strongly protected in a secular democracy, it is also important to bear in mind that a number of social evils take refuge as religious custom. These may be evils such as sati, slavery, devadasi, dowry, triple talaq, child marriage or any other. To seek their protection under law as religion would be a great folly. These practices neither conform with the basic tenets of human rights nor are they essential to religion. The commission recorded an interesting observation, “Our consultations with women’s groups suggest that religious identity is important to women, and personal laws along with language, culture etc often constitute a part of this identity and as an expression of ‘freedom of religion’.”

The commission has, therefore, dealt with laws that are discriminatory, rather than providing a UCC. Mere existence of differences does not imply discrimination, but democracy.

The easier procedure of divorce under Islamic law for men and women is also reflected in the relatively open attitudes towards the re-marriage of divorced and widowed women, a right that most Hindu women achieved through legislation.

Many Muslim countries such as Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and Pakistan have put tight measures of control to check polygamy. Pakistan passed a family law in 2015 that held second marriage without the permission of the existing wife illegal. Imposing restrictive conditions for polygamous arrangement has been carried out in various countries. The practice, however, continues to prevail in Saudi Arabia, Iran and Indonesia, besides India.

I think the best possible solution is to accept the Law Commission Report and keep the UCC on the back-burner and focus on the codification of different personal laws. Meanwhile, the government could set up an inter-faith committee to draw up a model UCC. AIMPLB should study the practice adopted in Muslim countries and could draw up a model nikahnama for the Muslims to follow, obviating the need/ possibility of court interference.

Let’s not forget that the chairman of the Law Commission, Justice B S Chauhan, had a distinguished record as a judge of the Supreme Court. His recommendations, arrived at after the widest ever consultations, cannot be brushed aside.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

S Y Quraishi is the former Chief Election Commissioner Of India and the author of The Population Myth: Islam, Family Planning And Politics In India