The footpaths on either side of the main road, underneath the Jamia Milia Islamia metro station, shelter almost 50 to 60 homeless people, who live there with their families. Rukhsana is one among them, who lives on the footpath with her husband and children. While most of the people living in this area refuse to speak or reveal anything about their difficult lives, Rukhsana reluctantly agrees to talk about her plight.

She has two children, and her son cannot speak. They move between Delhi and Lucknow, living on the railway platform at the Lucknow station on some days. Rukhsana cannot remember how long they have been living like this. When asked about her age, she first says she is 19 years old. Then she thinks for a bit and says, “utna to nahin hoga, 35 maan leejiye” (It must be more than that, consider that I’m 35).

They don’t have any means of livelihood and mostly depend on asking for alms to fill their stomachs. None of them possess any documents. Upon asking why this was the case, she says, “Banwana itna mehenga hai, kaun banwa dega?” (It is so expensive to get documents made, who will get them made for us?)

Rukhsana and the people who live around her fill water from a tap in the nearby “forest” - referring to an Irrigation Department enclosure which has a considerable tree-cover. Her family of four continued to stay on the footpath under the metro station even during the longest and harshest heat wave that Delhi saw in several years. As her daughter moves around barefoot, her husband uses a piece of waste plastic to fan himself. “Humare jaise log aur kahan jayenge?” (Where will people like us go?)

We ask her if she is familiar with the Delhi government’s initiative of Rain Baseras or homeless shelters. She doesn’t know what they are. Rukhsana or her family members have never been approached by any authorities to move to a shelter, nor has anyone spoken to them even during the Lok Sabha elections period. During the heatwave, Rukhsana and her children fell ill multiple times.

When asked whether they got themselves treated, she says that they went to a nearby private clinic to get medicines. But why didn’t they go to a government hospital? “Wahan dawa milne mein dikkat hoti hai”, she states (It is difficult to get medicines there). But private clinics must require payments, so how do they afford the medications? “It depends on whether we receive any money from the passersby. The days that we get some money, we buy some medicines for ourselves.”

Rukhsana’s story is similar to the stories of the more than 2 lakh population of homeless people who live on the roads in Delhi every day. As per government and NGO reports this year, fatalities among the homeless in Delhi broke a 22-year record, as most of the individuals who died were unable to get adequate and timely medical attention. The government shelter homes in the national capital have offered little respite due to poor infrastructure. A large number of these shelters have tin roofs, which further trap the heat and humidity from the day and do not let the space cool down even at night. Moreover, the number of shelters present in the city is drastically disproportionate to the number of homeless people who actually live on the streets.

The situation has been only marginally better for those who have houses of their own but are engaged in daily wage activities across the city. Pehelwan Chowk, a cluttered locality ahead of Batla House with narrow gullies running through it like veins, is inundated with trash and sewage water.

Mateen Bhai has been running a roti (flat bread) shop here for nearly 12 years. The shop consists of one humble room with walls that are lined with years of soot and smoke, while a tiny fan runs on the ceiling and a small table fan sits beside them as they work mechanically. This is where Mateen bhai, along with four more laborers, work around a burning furnace all day long to make rotis.

Mateen bhai comes from Kishanganj in Bihar and has left his family behind there to stay in Delhi with his workers in one room rented in the same area as his shop. Engaged in a profession that involves dealing with high exposure to heat, Mateen bhai found this year’s summer much more difficult to cope with as compared to the past few years. Mateen bhai has to buy water for the consumption at the shop every day, which comes at 10 rupees per can. On an average, they use 10 to 12 cans each day, which becomes a considerable burden on their expenses in summer, as their sales reduce during the season since most people prefer to consume rice in this weather. When asked how they dealt with the heatwave this year, Mateen bhai said that they did not have much option, except to sleep on the terrace during the nights, when the heat became unbearable. Javed, a labourer at Mateen’s shop hailing from Lucknow, states, “We cannot afford to get up and leave as this is what we do all year long and it’s the only job we know”.

While Mateen bhai’s profession does not allow him to leave and return home when the weather worsens, the laborers who are involved in the daily wage work that requires backbreaking physical exertion under the scorching sun, have been rushing back to their hometowns with the soaring temperatures.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Sanjay, 33, a resident of Bhagwan Nagar hailing from Kolkata, is employed on a contractual basis for loading and unloading of large parcels from the trains around the Nizamuddin Railway station area. Sanjay says that heat-related illness among his fellow workers like fever and weakness has been rampant, and so many of them have migrated back to their villages and hometowns that there aren’t enough hands to do all the work during the summer months.

In this area around the railway station alone, nearly 1000 men, mostly between the ages of 20 to 50, are employed without any registration or insurance on a daily basis. Aslam Ahmed, a 28 year-old who works alongside Sanjay, says that the biggest difficulty that they have been encountering in the heat is the lack of any toilet facilities or drinking water for the workers on site. They either bring drinking water from their homes or buy it, and relieve themselves by the railway tracks. At home too, there has been little respite from the heat due to incessant power cuts throughout the summer.

When asked why he thinks this summer has been particularly unbearable, or why the temperatures are rising steadily every year, Aslam says, “Aisa lagta hai ki suraj dharti se kareeb aata ja raha hai” (It feels as if the sun is coming closer to the Earth). Md. Ghayasuddin, 52, who works at a machine repair workshop in the Noor Jahan Masjid colony, shares a similar view as Aslam, about the rising heat. “Allah ka kehar hai”, he says (It is God wreaking havoc).

The heavy rains that hit Delhi in the later part of June may have brought some respite to the incessant heat for many, but they have brought along a fresh set of difficulties for those who have been surviving in temporarily-built shacks in the slums. Shehnaz, 28, who comes from Katihar and has been in Delhi for the past 9 years, lives in a self-styled hut in the Rani Garden basti near Geeta colony.

Living in an area that is surrounded by garbage, Shehnaz makes a living as a rag-picker so she can send her daughter to school. Her son has a mental disability. Shehnaz says that while the heat was definitely unbearable this year, living in the rains under a roof that is made of polythene sheets and leaks from all directions isn’t a respite either. As the garbage around starts flowing in the waters, the threat of various water-borne diseases looms large. Suresh Prasad, who has commissioned Shehnaz and has been living in this basti for 22 years, says that there is no one who reaches out to them for any kind of aid to help their condition. “If anyone collapsed while working in the heat, a few passersby would help the person to stand up on their feet again. But apart from that, we have received no help. As long as we can stand, we keep working”.

Suresh blames the heat waves and drastic weather fluctuations squarely on the air conditioners that run in the buildings that they are surrounded by. “The heat from their homes may have been expelled out due to their air conditioning, but we are left to bear its brunt outdoors”, he states emphatically.

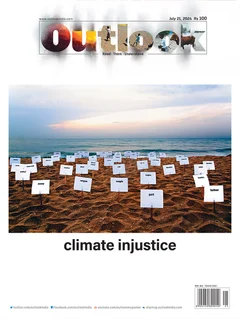

It becomes clear then, that while the climate crisis spells doom for every person across the country with the extreme weather conditions, its impact does not hit everyone equally. While certain sections of the society may be able to avail resources to ease their discomfort, their luxuries come at the cost of making the lives of those living on the margins even more difficult and unsustainable.

(This appeared in the print as 'Living On The Margins')