I AM home. Babi and Babuji are already in their room. Babi laughs her hearty laugh, seeing me tiptoe into her room. Babuji smiles his old smile. It is the smile of a child who is about to crack a magic trick. He is making the bed—one of the very few things he loves to do.

‘Remember this quilt?’ Babi says, taking a quilt out of a wooden box. ‘It is 100 years old today. Come and smell it. Do you know why it still smells the same? Because of this box. It preserves everything. Your Babuji got it made some days before our wedding…’ she goes on, marvelling at her belongings.

‘Sleep early tonight,’ says Babuji, giving me a hug and a kiss. The hug and kiss of a man who is reuniting with a grandchild separated two lifetimes ago.

‘Don’t worry! I will wake you up early tomorrow,’ says Babi. Her old habit of interjecting her husband.

‘The tonga will come at dawn and then…’ says Babuji.

ALSO READ: Kashmir: This Isn’t A Postcard Series

‘And then it will take us until lunchtime to reach Ladhoo,’ says Babi, cutting him off yet again. She’s doing it for me, and not to irritate him. Babuji has never known irritation in life.

‘Triloki Nath’s children are going to be there,’ she says, sensing my reluctance to go anywhere. Half of her world is outside, in the countryside and in other people’s homes. ‘They will take you to the orchard. Don’t be a pest and steal plums the way you did last time.’

‘This isn’t the season of plums,’ says Babuji. ‘Winter isn’t over yet.’

‘Don’t teach me about seasons,’ says Babi. ‘I have seen summer in winter, and winter in summer, haven’t I?’

‘There she goes again—the greatest raconteuse Kashmir will ever see,’ Babuji whispers to me.

Nobody tells anecdotes and stories the way Babi does. She will make you believe the unbelievable. For instance, she will tell you about the day a crow whispered into her ear and spilled the beans about her husband. Something nobody knew. Not even the husband. And then her tryst with an elephant when she carried her calf across a river.

‘Take this along,’ says Babuji, handing me his transistor. ‘It should work after we get the batteries replaced.’

I switch the transistor on. A song plays. And then the unthinkable happens.

‘Babi, Babuji, where are you?’

ALSO READ: Routes Of Grief: Two Translations

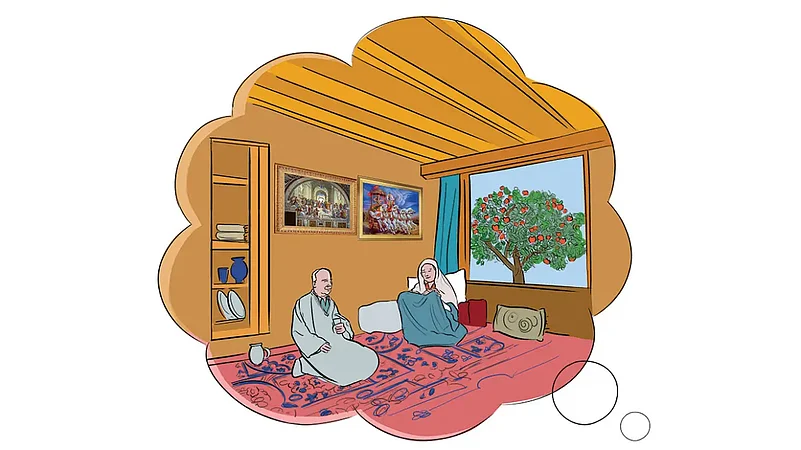

Babi and Babuji are sitting next to each other in their room with smiles beaming on their faces. On the wall are two paintings—The School of Athens by Raphael and Krishna taming the five horses of Arjuna’s chariot. The window frames an apple tree.

***

I am now going to tell you about a secret dream. The dream is 33 years long, with a day equalling a year, a year equalling a century. I have been dreaming this dream over and over again for the past 33 years. Thirty three years are two full lives. I came here when I was 15. Now I am 48. I have kept a close watch over time. No one knows of my secret existence, except a bird which comes here every evening to feed her chicks in a nest high atop the tree next to my cabin. She doesn’t look like any of the birds I have seen in my life. The only birds I have seen are crows, sparrows, pigeons, kites, and kingfishers. But she isn’t any of them.

The bird whispers about you. I trust the bird because only you are capable of such things. She hides a smile behind her tears and tears behind her smile. Such terrible things that can’t even be dreamt.

ALSO READ: Kashmir: Of ‘Stories’ And Friends

‘She has now forgotten you,’ says the bird.

‘You are lying. She will never forget me. She will forget herself but not me.’

The bird wants me to hate you, to forget you and never to think of you. But how will I ever do that? I named her after you. Yours is the only name I know.

***

It is the spring equinox of the year 2090. A 100 years have passed since I was forced to leave Kashmir. Not Kashmir, the place; but Kashmir, the person. You, I mean!

ALSO READ: The ‘Homeland’ Dream Of Kashmiri Pandits

I have a dream and a memory of the day which is yet to come. An almost impossible day that is about to be returned to me. A day that has equally waited for me. As if I have belonged to it from the time I wasn’t even born. As if the curse were over and the boon granted by the little bird, the lone messenger of the most supreme of celestial beings.

‘You shall come back to me in the spring of 2090,’ sings the little bird.

Me: But what if I die before that happens?

She: What if you don’t? What will you do that day?

ALSO READ: Kashmir Files: Memories Of Another Day

Me: Don’t you know already?

She: What did you do on the day you left?

Me: I didn’t think it would be forever.

She: You mean a 100 years?

Me: Is a 100 years forever?

She: Will you cry now that you’re back?

Me: I have cried enough. It is time to be happy now. I will laugh like that mad person who died laughing, telling people that they have gone mad, seeing them unleash hate upon their own friends and neighbours.

She: And you will…

Me: I will go to the places where Babi and Babuji wanted to go.

She: Why would you want to step out of the house now that you’re back after a century?

Me: I have some unfinished work in those places. Shouldn’t I finish what they were not allowed to finish?

She: Would you ever want to go back to the places where you spent these 100 years?

Me: One last time, for these are the places where I learnt how to sleep on burning sand. Where I learnt how to hide my scars, even from myself. Where I learnt how to be silent, how to love, how to wait and how to dream.

***

There was a time I couldn’t live without you. Not even for a second. I missed you even when you were next to me. Babuji is working in his laboratory, examining samples of blood. I am waiting for him to break for lunch. That is when he will teach me how to identify cells using his microscope. ‘Look how beautiful these cells are,’ he says, pointing to their dance-like movements. ‘Some day you should learn how to cure the sick ones.’ Babuji has never been sad in his life. He has always known boundless happiness because his happiness is others’ happiness. He sees beauty and goodness in every human because the very cells which give them life are made of nothing but beauty and goodness. He has deep love for even those who have never loved and who don’t know what love is. He is the ambassador of humanism in the entire locality. ‘What will you do with my memory after I am gone?’ he says, as we start cycling back home.

Babi is in the courtyard, making apple jam. The first person to taste it will not be her husband but her grandchild.

ALSO READ: Kashmir: The Political Capital Of Pain

I am sitting on the branch of a plum tree listening to a song playing on Babuji’s transistor. Plums hang low on the branches, tempting me to pluck them. But I have promised Babuji and Babi that I wouldn’t even touch them. Triloki Nath’s family is preparing for the wedding feast. In the courtyard of the house, a boy is chasing crows away. ‘Crows are harbingers of bad news,’ his mother says. ‘Don’t let them near us.’

Triloki Nath comes out of the house with saplings in his hand. ‘Come with me, all of you,’ he says to the kids. ‘I am going to teach you how to plant a sapling. Years from now, these apple trees will be yours.’

ALSO READ: Kashmir: Requiem For A Dream

From inside the house comes laughter. Everyone is laughing at Babi’s jokes. Babuji is sitting in a corner, lost in his own solitary world, content in being a sunrise-to-sunset man.

I close my eyes, thinking that this day will last forever.

***

Whenever the history of the happiest people that ever lived will be written, Babi (Uma Shori Gigoo) and Babuji (Omkar Nath Gigoo), to whom home meant everything, will be spoken of in the happiest terms. In 1996, six years after being forced out of his home in Kashmir, Babuji lost his memory and sense of hearing, but the forever smile on his face proved that he left this world happy after tasting the sweetest nectar of life. Babi breathed her last in a hospital in Srinagar, one day before having her last wish fulfilled—to be home one last time.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Loss and Longing")

ALSO READ

Siddhartha Gigoo is a Commonwealth Prize-winning author