In the 1990s, an ‘RSS-leaning coconut tree’ belonging to a Hindu household often damaged the clay roof-tiles of a Muslim shrine in a small Kerala village. The coconuts would fall on the roof of the mosque, causing such damage that the issue soon built up communal tension. Repeated requests to cut the offending tree fell on deaf ears. Finally, both parties decided to take the matter for mediation to the much-revered spiritual leader, Panakkad Syed Mohammedali Shihab Thangal (1936-2009), the supremo of the Indian Union Muslim League.

After a patient hearing of both sides, the Thangal took out some money, gave it to the president of the mosque committee and declared, “The masjid has to be demolished. The clay roof-tiles should be replaced with concrete.” Popular belief—call it superstition if you will—is that if the first donation is from the Thangal, his blessings will follow the project until its successful completion. The parties returned to their Malabar village by night. The old lady in the Hindu household was distraught when told of the Thangal’s verdict and chided her son, at the age ripe for Hindutva, for the curse he’d brought upon the family. She rushed in a car to the Thangal that very night. The wise old man received her with grace and dismissed in his famously reticent and soft manner her promise of cutting the tree and profuse apologies for her son’s indiscretion. “The coconut tree is the elixir of our life,” the Thangal said. “It should be protected at any cost.”

This is Malappuram for you, dear Subramanian Swamy. Why him? Because the 77-year-old politician, with the BJP since 2013, has for some time been waxing belligerent about the “pathetic plight of the Hindus in Kashmir and Malappuram”. It’s of a piece with the numerous canards the Sangh parivar has been spreading about Malappuram in its cynical attempts to import Indo-Gangetic barbarism into the harmonious social fabric of Kerala. Malappuram, a Muslim-majority (70 per cent) district upstate, is being demonised ad nauseam in order to whip up communal passions in the rest of Kerala, to the obvious advantage of the saffron party.

Pluralist Idealism Vs Intra-Communal Chauvinism

The weird irony of Malappuram, or for that matter the whole of Malabar, is that inter-communal relations are always managed in idealistic terms while intra-communal issues are dealt with in an extremely sectarian and belligerent manner. Much of the goodwill showered on the Hindus in Malappuram by the majority Muslims may never be on offer when it comes to relations between the three predominant markers of sectarian schism within the Kerala Muslim community: traditionalist, Salafist and Islamist. Mind you, the first two of the three markers of sectarian identities are host to further splits within. That violence between them, verbal and physical, is so commonplace that it hardly attracts wide media attention.

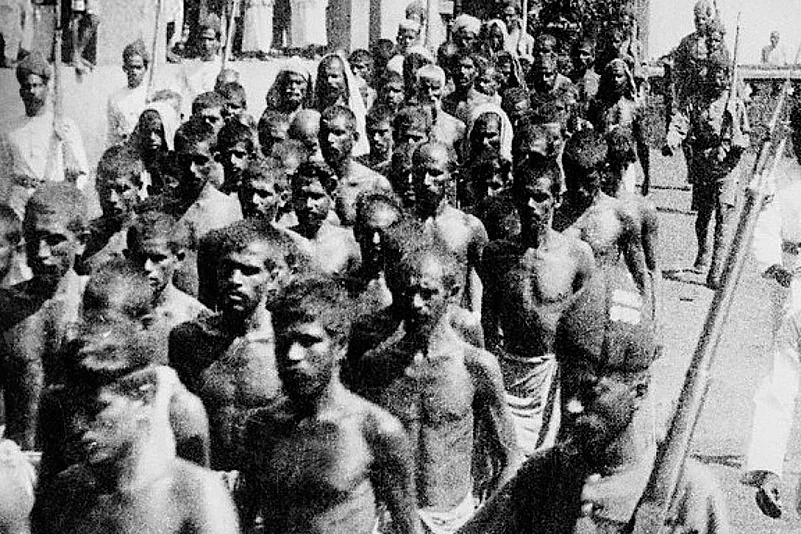

The 1921 Mappila rebellion was the last instance of communal violence in Malappuram.

In pure anthropological terms, Malappuram is in fact a fascinating case study for a place where the entire majority community, in this instance the Muslims, stands united in favour of harmonious social relations with the distinctive ‘other’ while all markers of ‘othering’ within are considered unworthy of humane treatment! In the Mappila folk consciousness, being communal is a cardinal sin while being religiously sectarian and schismatically bellicose is kosher, even essential for salvation in the hereafter. In fact, if they choose to be as nice to the different sects within as they are naturally to the Hindus or Christians or to ‘outsiders’ in general, Malappuram can actually become the world’s most beautiful experiment in pluralism! But Malappuram decries intra-Islamic pluralism while it not only celebrates but also romanticises inter-communal fraternity.

The sectarian hostilities among the Muslims of Malappuram are relatively less known outside the Muslim fold, but the famed inter-communal harmony within the district between the Muslims and the Hindus is widely acknowledged in the state (if, alas, not outside). No major communal conflict has occurred in the district for nearly a century, although pseudo-nationalists often confuse Malappuram with Pakistan. The last memories of communal hatred go back as far as the Mappila rebellion of 1921 or the expeditions of Tipu Sultan in the 18th century. Although the agrarian and anti-colonial nature of the former and the expansionist power designs of the latter are not to be disputed as the predominant tropes of the periods, there is no denying the not-so-subtle manifestations of naked Muslim fanaticism that ruled the roost during both the occasions. But it will be unfair not to recognise that the Mappilas of Malabar learned their lessons and never nurtured exclusionary tendencies ever since.

Historical Trajectory

Hindu-Muslim relations in Malabar did undergo many ups and downs over long centuries. The nature of relations and the intensity of closeness or degree of distance fluctuated throughout history until India gained independence and the state of Kerala was formed on the basis of Malayalam as the common language. The pre-colonial period hardly saw a significant rupture in inter-communal relations, though historians mention some sporadic localised incidents. This was primarily due to two facts—as Theodore Gabriel points out in his book, Hindu-Muslim Relations in North Malabar, 1498-1947. First, Islam came to the Kerala coast via peaceful traders from Arabia. It was in their vital interests to forge harmonious and symbiotic relations with their hosts. Second, the Muslims in Kerala never made any attempt at political conquest in spite of the military and financial muscle at their disposal. They functioned largely as an orderly component of the society, contributing substantially to collective security and economic welfare and to the cultural pool. They also played a leading political role in the dominions of the region’s Hindu kings, particularly under the Zamorin of Calicut, dealing with the kings from a standpoint of self-confidence and latent power rather than subservience.

But this state of amity was not to last very long, as powerful foreign elements soon entered the scene and bitter political rivalries ensued. The solid economic base of the Muslims in the region faced an existential challenge from the Portuguese. The accommodation and tolerance extended to the Muslims by the Hindu kings were primarily because of the prosperity that they had brought to the land. When the Hindu kings saw in the Portuguese a powerful contender for that role and felt they could bring better benefits in terms of revenues and military wherewithal, all of them except the Zamorin shifted their patronage to the new arrivals, infuriating the Muslims. This marked the beginning of a long period that saw a wane in the trust between the two communities.

Hostilities thus generated during the Portuguese era were sharpened during the rule of Malabar by Hyder Ali and his elder son Tipu (1766-1792). The Muslims welcomed the Mysoreans, for it meant for them an end to the deprivations and loss of status brought by the Portuguese. The brutalities the Mysoreans unleashed on the Hindus in complicity with segments of the local Muslim community exacerbated the mutual distrust and hostility. By the time Tipu ceded Malabar to the British under the Seringapatanam Treaty of 1792, the marginalisation of the Muslims that began with the advent of the Portuguese was at its nadir. While they resented the Hindus for supporting the Portuguese, the Hindus felt betrayed by the support the Muslims extended to the Mysoreans. In short, the relationship between the two communities was extremely strained by the time the British came into Malabar.

The period of British rule in Malabar saw the eruption of a series of armed uprisings by the Muslims against the British government and the Hindu landlords (Against Lord and State, in historian K.N. Panikkar’s memorable coinage). Although agrarian protests in essence, the uprisings that reached its apogee in the 1921 Mappila rebellion had clear communal overtones. The subsequent three decades saw many instances of the growing divide between the two communities in Malabar, including the demand for Mappilastan and the overwhelming support of some Malabari Muslims to Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League and the demand for Pakistan. In hindsight, a Muslim in Kerala supporting the demand for Pakistan appears ridiculously un-geographical and counterintuitive, but it reflects the mutual distrust that existed between the communities at the time.

Post-Independence Transformations

However, the Muslim leadership in Malabar seems to have learned their lessons from the tragic events of Partition and the disastrous effects of communal politics. The Indian Union Muslim League, which undoubtedly was a relic of Jinnah’s Muslim League but with unmistakable Malayali characteristics, adjusted its politics and strategies to the values of India’s secular constitution. It took utmost care to function as a communitarian party committed to working for the constitutionally guaranteed rights of the minorities. It began to articulate its politics in a language and idiom totally in sync with Kerala’s cherished pluralist traditions. That its stronghold was the Muslim-majority district of Malappuram made it all the more conscious of the importance of fostering harmonious Hindu-Muslim relations. The distinctive feature of the Muslim League in Kerala is that it strove to keep the community at the centre of the state’s politics, unlike other Muslim political formations elsewhere in India that revelled in confessional isolationism. As a result, the Kerala Muslims emerged as probably the only community of that faith in India that achieved genuine political empowerment on the one hand and, on the other, lived out the promise of equal citizenship enshrined in the Constitution.

Targeting Malappuram

Once the culture of communal harmony that thrives in Malappuram is sabotaged, the Hindutva designs for the state become easier to realise. The bogey of Hindus under threat in a Muslim-majority district can help majoritarian mobilisation in other parts of the state, but most of the Muslims and Hindus have foiled such cynical moves until now. In recent times, instances of temple desecrations increased in the district, immediately followed by protests by Hindutva organisations that pointed fingers at Muslim outfits. Huge social media campaigns also ensued, demanding that refugee camps be opened for Malappuram’s Hindus in other parts of the state. But the designs failed miserably because the culprits behind the desecrations turned out to be criminals with Hindu names.

Late spiritual leader Shihab Thangal (centre) was a proponent of peace.

The collective wisdom of the people of the district was on full display last year when RSS goons killed a young Hindu convert to Islam in Kodinhi village. Hindu and Muslim zealots did their best to fish in troubled waters, but the village’s Islamic leadership immediately called a meeting of families from both the communities, who decided to thwart all such attempts and maintain peace. They proudly recalled that the Juma Masjid in the village had donated the land on which the Koorba Bhagavati Temple stood.

When the Shree Lakshmi Narasimha Murthy Vishnu Temple in Punnathala village hosting Iftar for hundreds of Muslims this year grabbed headlines, the temple authorities dismissed the hype as unwarranted, saying they have been doing it for decades. The times have become so cynical that normal social gestures of the past have come to be seen as extraordinary spectacles of communal harmony. The results of the recent bypoll to the Malappuram parliamentary constituency was another fitting reply to the canards spread against the district. In a district where the Hindus are said to be under threat, a large majority of Hindus cast their votes in favour of the two Muslim candidates representing the Muslim League and the CPI(M), leaving the BJP with just about 65,000 votes. That the BJP candidate promised the voters quality beef if elected was a hilarious side story of the election.

Ideals Intact But Threats Galore

Hilly Malappuram, contrary to stereotype, is indeed an island of hope in a sea of communal venom. But it will be a mere fantasy to wish it will remain this way for long. Hindu and Muslim fanaticisms are on the rise. There are a few fringe groups that spare no opportunity to instigate Muslims to react violently to provocations from the Hindutva outfits. The support base of Hindutva organisations has also grown steadily over the years, though not to an alarming extent. But the wisdom and patience characteristic of the district’s Muslim leadership has prevailed so far. The Hindus in the district also have complete faith in this leadership and its commitment to the collective well-being of the people regardless of their religious identity.

The story narrated at the start is one of the numerous instances of how that mutual faith is instilled and sustained over the years. The solution the Thangal offered for the problem at hand may not have been to the liking of the extremist elements from both sides of the divide, but it kept the peace in a way that generated enormous goodwill. The role of the various mainstream Muslim organisations in keeping the social fabric of the district is commendable. The Muslim League and the Thangals of Panakkad continue to consider the preservation of harmony in the district as their primary responsibility, refusing to fall for populist instincts.

Will Malappuram remain this way for long? Can’t say. So long as it does, harmony in the rest of Kerala will prevail. Once Malappuram falters, the rest of the state will, too.

***

Hillock Of Hope

- Muslim-majority (70.25%) Malappuram can be the world’s most beautiful experiment in pluralism.

- No major communal conflict has occurred in this north Kerala district since the 1921 Mappila rebellion.

- Malabar’s Muslim leadership has been for communal harmony. Result: genuine political empowerment.

- The Hindus in the district also have complete faith in the local leadership and its commitment to the collective wellbeing of the people regardless of their religious identity.

Shajahan Madampat is a cultural critic and commentator, writing in Malayalam and English.