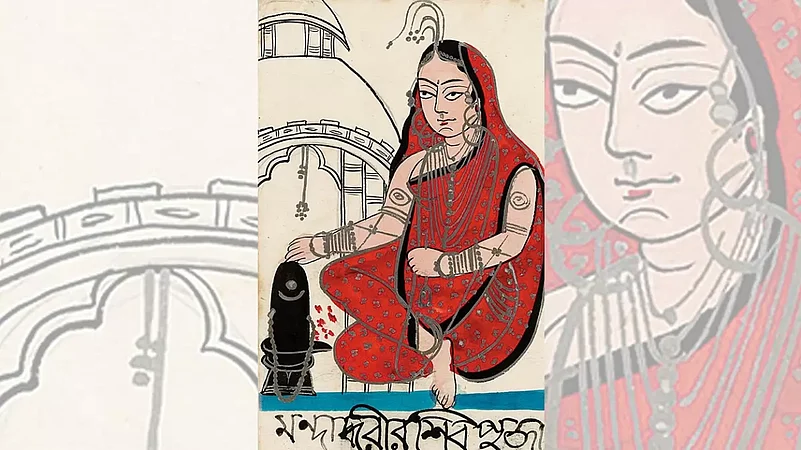

Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Thara, Mandodari thatha,

Panchakanya smaren nithyam maha pathaka nasanam

Even though this Panchakanya shloka composed of five women characters from popular Hindu mythologies—presumably evoked to dispel sin—gives space to Mandodari, little is written about the ‘Queen of Lanka’. While different Ramayanas across space and time refer to Mandodari as the wife of king Ravana, her agency as a queen has always been denied.

Who is Mandodari? Is she just the beautiful wife with a slanted waist as the meaning of her name suggests? Or, is she the moral fulcrum of a nation that was facing an onslaught due to its ruler’s masculine ego and ideological bankruptcy?

Since the days of Valmiki Ramayana, the birth of Mandodari has been a contested instance. According to Valmiki Ramayana, which has been echoed by several others in the following era, her birth was connected to Madhura, an apsara, who fell in love with Lord Shiva and wanted to marry him.

Infuriated by this immoral transgression, Shiva’s wife Parvati turned her into a frog. Shiva—known as the most merciful— nullified the curse and told her that she would reincarnate as a beautiful woman and would get married to a valorous king. Consequently, the asura king Mayasura and his wife Hema found her in a well and ‘Mandodari’ was born.

However, some accounts refer to her as a nymph who came down from heaven with the sole purpose of destroying Ravana. Notably, a few mythologists even note that Ravana received Lanka as a dowry from Mandodari’s father Mayasura. So, the role of Mandodari in the Ramayana lies far beyond an objectified beautiful woman. A deep dive into different representations unveils different shades of her characters— sometimes virtuous, and at other times, complicit in crime to safeguard the nation.

Varsha Adalja’s Gujarati play titled Mandodari reworks the ‘pativrata’ (dutiful wife) myth and brings out the queen who was well aware of the politics of the time. Here, Mandodari is found in a different role.

When Kaaldevata (Lord of death) comes to her declaring his intention to destroy Lanka; instead of being torn between her designated roles as the ‘Consort of the Asura King’ and the ‘Queen of the state’—she chose to be the latter and vows to save the country. Challenging Kaaldevata’s ‘game of deception’, she invents the ‘Chaturanga’ (modern chess) and allegorically says: “You may be aware, lord, that I have invented a game that can be played with pawns.”

However, against the binary of Kshatriya masculinity and Brahminical femininity, Adalja’s play, through its protagonist, inflicts a scathing attack on Ravana’s fragile male ego. Mandodari warns Ravana of the consequences of keeping Sita and reminds him of his fallibility: “This is the same Sita who used to play with Mahadev’s bow that you couldn’t even lift, remember?” Her reference to Sita’s swayamvara doesn’t invoke Rama’s supremacy as a protector; rather it talks about Sita’s prowess that the asura king should be feared of.

In front of the lord of death, Mandodari is found to be unfazed. Getting to know about the imminent and inevitable destruction of Lanka, she says: “I am Ravana’s wife and also his war strategist. I am well-versed in Saam, Daam, Danda and Bheda.” So, on the one hand, she tries to make Ravana aware of his limits, and on the other, she readies herself to protect the “prosperity, unity and morality” of the land.

Her assertion of the Asura identity against the projected supremacism of the Aryan race gets a new meaning when she reminds Sita of the historical oppression that the women of their tribes have been subjected to through the centuries.

When Sita asks her whether Asuras respect women at all, Mandodari responds: “When the victorious kings confiscate kingdoms, don’t they also take the womenfolk of the defeated kings? The gods keep apsaras for enjoyment. Your father-in-law has several queens”. This statement not only strips the Aryans of any moral high ground, it also challenges their condescending attitude toward asuras.

However, the ‘queen’ Mandodari comes out more vibrantly in Manini J. Anandani’s book Mandodari: Queen of Lanka as she marries Vibhishana, after the death of Ravana, out of ‘political necessity’. “My marriage with Vibhishana was a political necessity. Thinking about Dashaanan’s many wives that I had envied and he had claimed to be ‘political necessities’ made me laugh now. For the first time, I was a queen before I was a wife,” says the queen.

While several versions of the Ramayana end in Yuddha Kanda where Rama and Sita come back from exile, Manini transcends it to explore the possibility of Mandodari’s life after Ravana’s death. Some versions say that Rama convinced Vibhishan to marry Mandodari so that the people of Lanka accept him as the king, but there is no reference to this episode in Valmiki’s version or any mainstream version of the Ramayana.

“I wanted to give prominence to Mandodari’s voice in my retelling and wanted the readers to peruse her individualistic character instead of merely being referred to as ‘Ravana’s wife.’ After all, she had her own identity and she reigned as the Queen of Lanka even after Ravana’s death,” says Manini.

Referring to Mandodari’s efforts to restrain Ravana from engaging in war, author and peacebuilder Urmi Chanda says: “In some versions, it is she who stops Ravana from killing Sita and asks him to make do with other wives, and elsewhere she asks Vibhishana to side with Rama which shows her righteousness. She may be labelled as weak or disloyal for these actions, but sometimes peace is a path paved with many compromises, especially of one’s ego.”

Within the bounds of patriarchal and royal limitations, Mandodari exercises her agency in the best ways possible with peace as an intention. In a hyper-masculine story about guts and glory, a woman trying to step in for peace, justice and reconciliation, is a welcome change, she adds.

Even after playing such crucial political roles, why has Mandodari always been sidelined, even in retellings? Koral Dasgupta, the author of the Sati series that gives perspectives to different mythological women characters, says: “Very little is available about Mandodari in the Ramayana. It shows that she was a practical, farsighted, loyal, and righteous queen. I am not surprised. The villain’s wife is not important in a story unless she is an accused or a victim in the core plot.”

The silence looms large when anybody tries to examine Mandodari’s cognitive perception. In the words of Manini: “In most of the versions, she has been portrayed as stoic in chaotic situations. I simply think, as a society, we were so focused on deifying the central male characters that somewhere we may have neglected the female characters of the epic.”

Against this backdrop, more feminist readings and imaginations of Mandodari are necessary to read between the lines. As Chanda says, with time, the audiences of the thousands of Ramayanas want to “see her queenliness to grow”.

Beyond the image of pativrata, the virtuous wife who envied Sita, Mandodari needs to be restored to her own Kingdom— perhaps as the lost queen.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Lost Queen')