The north-eastern state of Manipur has been in the spate of violence for nearly two months now with conflict between two ethnic groups—dominant Meiteis and tribal Kukis—deepening into irreparable schisms. The conflict, which started on May 3, has already claimed 120 lives (officially) and over 3,000 have been reported injured. Over 50,000 people have been displaced from their homes.

But who is causing the violence in Manipur?

Violent clashes broke out in Manipur after a ‘Tribal Solidarity March’ was organised in the hill districts on May 3 to protest against the Meitei community’s demand for Scheduled Tribe (ST) status. However, Kuki leaders and community members Outlook spoke with claim that the reasons behind the Kuki-Meitei clash run much deeper than the Meiteis’ ST demand.

As of now, militants belonging to both, Kuki and Meitei groups are being accused of causing violence by the other. While the hill-inhabiting Kukis claim new-formed Meitei groups like Meitei Leepun and Arambai Tenggol are carrying out “genocide” against Kukis with the support of state forces, the Meitei community in and around the Imphal Valley claims that militant Kuki groups under the Suspension of Operations (SoO) agreement is behind the violence.

Earlier, Chief Minister N Biren Singh had said that security forces have killed 40 “militants” in Manipur in an effort to counter the violence. More recently, a team of 23 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) and leaders, including legislators belonging to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), National People’s Party (NPP), and Janata Dal (United) in Manipur urged the Union Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman to take action against Kuki militant groups under SoO agreement, accusing them of violating ceasefire ground rules.

As per reports, the group, which included Rajya Sabha Member of Parliament (MP) Leishemba Sanajaoba, has demanded that cadres of the SoO groups be brought back to their respective designated camps in order to curb the casualties in the ongoing violence.

Manipur and ‘Militancy’

The former princely state of Manipur formally became a part of the Union of India in 1972. Since then (and in fact from before that), the state has broadly seen two parallel kinds of militant movements—one led by the Meiteis for Kangleipak and cessation from India and the other led by Kuki-Zomi groups demanding a separate homeland for Kukis.

The Kuki National Organisation (KNO) is an umbrella group of 17 Kuki insurgent groups, and the United People’s Front (UPF) represents eight other Kuki insurgent groups. The UPF, which is another umbrella organisation comprising Kuki-Zo revolutionary groups, was also formed in 2006. The political objectives of both, UPF and, KNO are identical and focus on the demand for separate statehood for the Kukis. However, it is to be noted that much of the Kuki-Zomi groups organised post-1993 as a way to counter Naga aggression.

Meanwhile, the Meiteis have been organising since the 50s against the unification of ‘Kangleipak’—the pre-British kingdom of Manipuri Meiteis in the Valley—with the Union of India. The United National Liberation Front (UNLF) was formed in 1964 demanding secession from India. This was followed by the emergence of a number of Meitei groups known as “Valley Insurgent Groups”, including the People’s Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK) and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). These groups functioned with the twin objective of cessation from India and warding off Naga aggression.

By the 80s, Manipur was declared a disturbed area but militancy in the region was brought under control with a series of ceasefire interventions with Kuki-Zomi groups. The Valley Insurgent Groups, however, technically remain active as they have never entered an official agreement with the Centre or even participated in any peace talks over the years. Now, new groups like Arambai Tenggol and Meieti Leepun (led by Pramod Singh) have been at the centre of the current violence unfolding in Manipur. Leepun, a “cultural” organisation working for preserving Meitei identity and religion, has publicly warned of further retaliation and “a bigger blow is to come”, as reported by The Indian Express.

What is SoO?

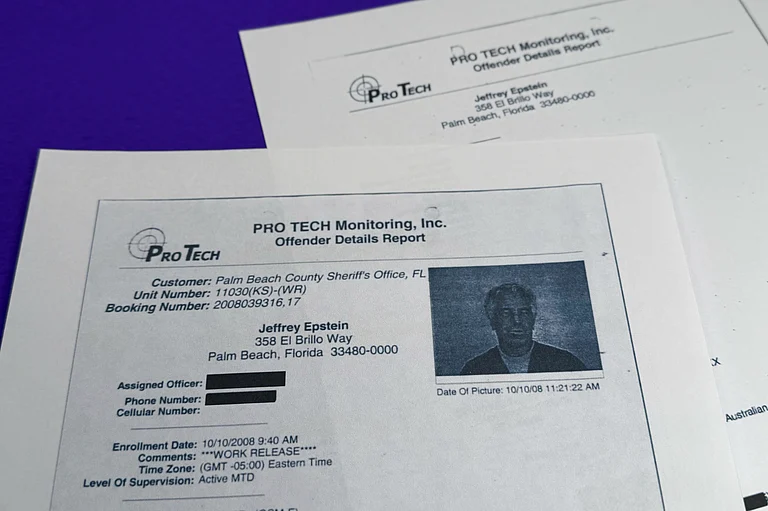

On August 10, 2005, Kuki National Organisation (KNO) signed the Suspension of Operations (SoO) [Ceasefire] with the Army which was followed by another SoO (tripartite agreement) on August 22, 2008, signed between the Government of India, KNO and the Government of Manipur state. The UPF also signed the same SoO on August 22, 2008.

At present, there are about 2,200 cadres in the SoO groups staying in their 14 designated camps, says Ngamjahao Kipgen, a researcher of Kuki identity, who teaches sociology at IIT Guwahati.

Tripartite means an agreement that involves State, the Centre and the designated group. “It is a common strategy across various states in the Northeast,” says Samrat Sinha, Professor at Jindal Global Law School (JGLS) of O.P. Jindal Global University (JGU). “Two key components of the SoO arrangements are funding and monitoring. For SoO groups, the funding mechanism is unclear, but I think the Centre provides funding while the state disburses and jointly monitors with central forces,” he states.

Speaking on Manipur, Sinha adds that the state presents a “complex” case and it is difficult to say if the present violence was exacerbated by the existence of SoO camps, as has been alleged by the dominant community.

“It is difficult to judge the failure or success of the SoO setup. It was successful insofar the situation did not emerge earlier and there was some mechanism in place from 2008. SoO could have led to some kind of political settlement but the future is uncertain, Sinha states, adding that in the SoO, there are many micro-level variations, and is not functional in the fringe villages that border the Valley and the hills. This is the region where violence has been sustained in the past month.

While Manipur legislators and Meitei leadership have been blaming Kuki militants for the violence, Kukis have claimed that it’s actually Meitei militants backed by CM Biren Singh and the Manipur Police Commandos that have been carrying out attacks on Kuki villages.

“Many of the SoO camps have been robbed of arms and ammunition during the violence when other groups attacked Kuki areas. And if Kuki militants were so active, why would Kuki villages be seeking protection from the Army and the Centre?” asks DJ Haokip, a Kuki Student Organisation (KSO) leader from Churachandpur where the first incident of violence broke out on May 3. Amid rumours of SoO camps being robbed of arms and ammunition, Army officials were quoted by a report in Hindustan Times on June 9 as saying that almost all weapons of Kuki militant groups under SoO agreement in Manipur remain intact and in their designated camps.

Since the violence in May, Kukis have blocked National Highway 2, the key supply lifeline of the Valley, while Imphal remains unsafe for Kukis who have been exterminated from the Valley. Ten tribal MLAs belonging to Kuki community have also demanded a separate administration for hill districts in Manipur. While the demand strengthened after the May 3 violence, the calls for a separate administration and/or separate “homeland” or Kukiland for the Kukis have been recurrent demands among Kukis and the key reason for Kuki militancy.

Coexistence, conflict and the ‘Search for Homeland’

The Kukis are said to have migrated and settled in the present inhabited place (present-day Manipur) as early as the pre-historic times along with or after the Meitei advent in Manipur Valley, explains Kipgen.

The Kuki people are today divided by the political boundary of India and Myanmar. But there is an idea of a single homeland for all Kukis-Zale’n-gam. While the physical demarcations of this homeland might be sketchy, the place exists in the memories of the Kuki ancestors.

“Zale’n-gam is an ideological concept propounded by P S Haokip, the President of the KNO, which means ‘freedom of the people in their land’,” Kipgen explains.

Haokip propagated the ideology of Zale’n-gam as the means to unite the erstwhile ancestral domain of the Kukis prior to the British rule and restore the Kuki nation Zale’n-gam. It encapsulates and expounds the essence of Kuki history and nationalism and the restoration of the erstwhile Kuki territory in the pre-colonial period.

“There has been a desire to unify all the Kuki inhabited areas into a single administrative unit. Currently, their demand is for a separate homeland/Kukiland within the framework of the Indian Constitution,” Kipgen states, referring to the demand for separate administration raised by Kukis following the May 3 violence.

However, Kipgen highlights that despite the Kukis’ search for Zale’n-gam beyond the Meitei kingdom of Kangleipak (Manipur), the two communities have coexisted peacefully for time immemorial.

“The Kukis and Meiteis have more or less followed the principle of peaceful co-existence. This can be necessitated from the assistance extended to the Meitei maharajah by the Kuki chiefs in the erstwhile period,” he states.

“For instance, the Meitei King Chourajit could not fight the Ava’s (Burmese) army in 1810 and therefore, asked the Kukis for help by declaring “the hills surround Manipur Golden land like a stockade and the tribal guards the stockades”, Kipgen states. And in due course of time, the Kuki chiefs also sent their irregulars to guard the maharajah and his Kingdom so as to resist the merger agreement on the eve of Manipur’s annexation to India in 1949 when Manipur was merged with the Indian Union.

“The merger led to a wider gulf between the hill dwellers and the plainsmen. Under this new system, various hill areas under the British administration became a ‘Scheduled Area’ and the Acts forbid the plain peoples (Meiteis) to settle in tribal areas/the hilly region. This clearly alienates the Meiteis and the tribals (the Nagas and the Kukis),” Kipgen adds.

To put it in a nutshell, it is pertinent to note that since time immemorial, Kangleipak (Manipur) and Zale’n-gam (Kukiland) have been in peaceful co-existence with mutual respect for territorial integrity and that the inhabitants vis-à-vis the Meiteis and the Kukis have been living peacefully in their own respective territories without any interference in each other’s internal affairs.

It would be prudent to recall and retrospect the events that occurred in 1891 (Khongjom War also known as Anglo-Manipur War) and in 1917–1919 (Anglo-Kuki War) in which the Meitei’s land (Kangleipak/Manipur) and the Zale’n-gam were subjugated and conquered successively by the British colonial which put them under the same administration.

The Hill-Valley Divide

The ongoing violence has further deepened the divide between hills and plains-people, which is at the heart of the tribal militancy.

In the Art of Not Being Governed—An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, anthropologist James C Scott outlines how state formation in the valleys creates sections that are “non-state” that inhabit the hills. At the core of this distinction between state and non-state is “surplus”.

Imphal-based political analyst Pradip Phanjouban explains that surplus is the necessary first step of the process of state formation and intellectual/political/economic activity. Thus, communities practicing shifting agriculture in hills and making frugal produce that lasts from season to season remained left out of the process, meaning they became “non-state”.

This distinction between state and non-state makes itself felt across various metrics—the style of warfare the two groups practice, (guerrilla vs structured army), the style of governance (local vs national), and even their perception of concepts like “democracy”, “republic” or “freedom”. It can also be seen in the state’s response to these groups in that areas considered “non-state” often suffer from lack of resources. A case in point are the hill regions of Manipur that remain woefully underdeveloped. All major universities, colleges, hospitals, government offices and emergency services are located in Imphal, and the nearby valley region.

With the focus of the centre as well as the state fixed on punishing “militants” rather than finding peaceful solution to the ethnic conflict through dialogue, the hunting of Kuki “militants” perhaps once again brings to the fore this divide between state and non-state, where armed forces of the state are considered legal while armed forces of the “non-state” are considered militant.

The Manipur crisis necessitates the need for not just military intervention but also socio-ethnographic and geopolitical strategising and inter-community dialogue that includes all stakeholders in an equal capacity. A Khongsai, the Kuki Innpi President, says: “At present, Kukis are not equally represented in the peace talks”. Slamming the Centre and state’s efforts to “restore normalcy” in the violence-hit districts, Khongsai adds, “peace cannot be violently imposed in the name of restoring normalcy. This matter requires deeper introspection”.