“There’s no art to find the mind’s construction in the face,” wrote Shakespeare. Present-day scholars would disagree. Desmond Morris’s classic People Watching, Albert Mehrabian’s widely discussed Silent Messages and Paul Ekman’s extremely influential Emotions Revealed all suggest that our body language affords a fundamental glimpse into our thought processes. Stances, gait, facial expressions and hand gestures in the species Homo sapiens each tell their own fascinating story. Today, there’s a burgeoning global industry devoted to decoding the tell-tale signs of emotional attitude, especially where public figures are concerned. Consider, for instance, the media attention showered on Michelle Obama’s on-camera eye-roll at a bipartisan congressional lunch earlier this year. Interpretations of this single ocular act ranged from suggestions that the American First Lady had bad table manners to assertions that she was sceptical, distracted, amused, disgusted or surprised. Another recent furore involved Bill Gates’s one-handed handshake with the South Korean prime minister, his left hand casually resting in his pocket. Was Gates being disrespectful or just being himself? Was this a clash between Asian and western values or merely much ado about nothing?

It is a widely held perception that political talk in our own country has become progressively shriller. Every community is prone to instant insult and every higher-up delighted when his feet are caressed by the not-so-elevated. Perhaps we can lower the temperature a bit without necessarily becoming anodyne if we look at these issues from a somewhat different angle. The present essay arose out of a conversation with a colleague, Snehlata Jaswal, an experimental psychologist. We’d both independently observed, like many others, that Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi, also the bjp’s potential face for PM, had a particular ability to make himself the cynosure of all eyes. Several reasons could be adduced for this: the general political climate, the current crises of leadership in the BJP, as well the media amplification of Modi’s activities. However, the media had to have something to amplify in the first place. What was this?

Our impression was that Modi offered a textbook example of how verbal as well as non-verbal language is deployed in present-day politics, of how a dominant persona can suddenly emerge centrestage in the hurly-burly of a pre-election year where many narratives compete for attention. I should clarify at the outset that the aim of this article is certainly not to forecast Modi’s political future or to compare him with Rahul Gandhi. This I leave to the pundits. Instead, I wish to suggest through the preliminary research presented here that the discourse of politics shares a large, mostly unexplored boundary with other modes of thought.

The silent but inalienable presence of the non-verbal alongside speech is, I argue, particularly relevant to an analysis of political discourse. We know politicians to be overtly engaged in the art of persuasion, and we therefore look for spontaneous—or less hackneyed—signs that their rhetoric is trustworthy. Is what they say what they really think? This is where body language comes in, as Charles Darwin argued in his pioneering work, The Expression of Emotions in Man and the Animals (1872). Many studies in cutting-edge cognitive science have since taken Darwin’s insights forward. Such analyses have, however, rarely been undertaken in the Indian context. Keeping in mind the evolutionary background just mentioned, we began with three simple hypotheses in this perhaps first-ever study of its sort in India. These were the following:

First, the famous ‘polarisation’ always mentioned in connection with Modi would be related to patterns in his language output, since language is the main medium the human species use to their structure the world. Second, socially tense situations in this ‘world’, such as the one that surround Modi, are likely to arouse the basic fight-or-flight reactions which have evolved over millions of years. In the case of Modi’s very noticeable facial and hand gestures, our conjecture was that we would see more ‘fight’ gestures in conformity with the famous representation created by brain scientist Wilder Penfield. Third, the performative dimensions of both language and gesture, we hypothesised, were likely to be quite enhanced in the political arena, giving us the opportunity to observe the relationship between thoughts and emotions and their on-record public expressions that Darwin thought was so critical to the evolution of human societies across the globe. The research presented here examines one our most-watched politicians along three axes—the linguistic, the gestural and the performative.

Making Every Bias Show, Count By Word Count

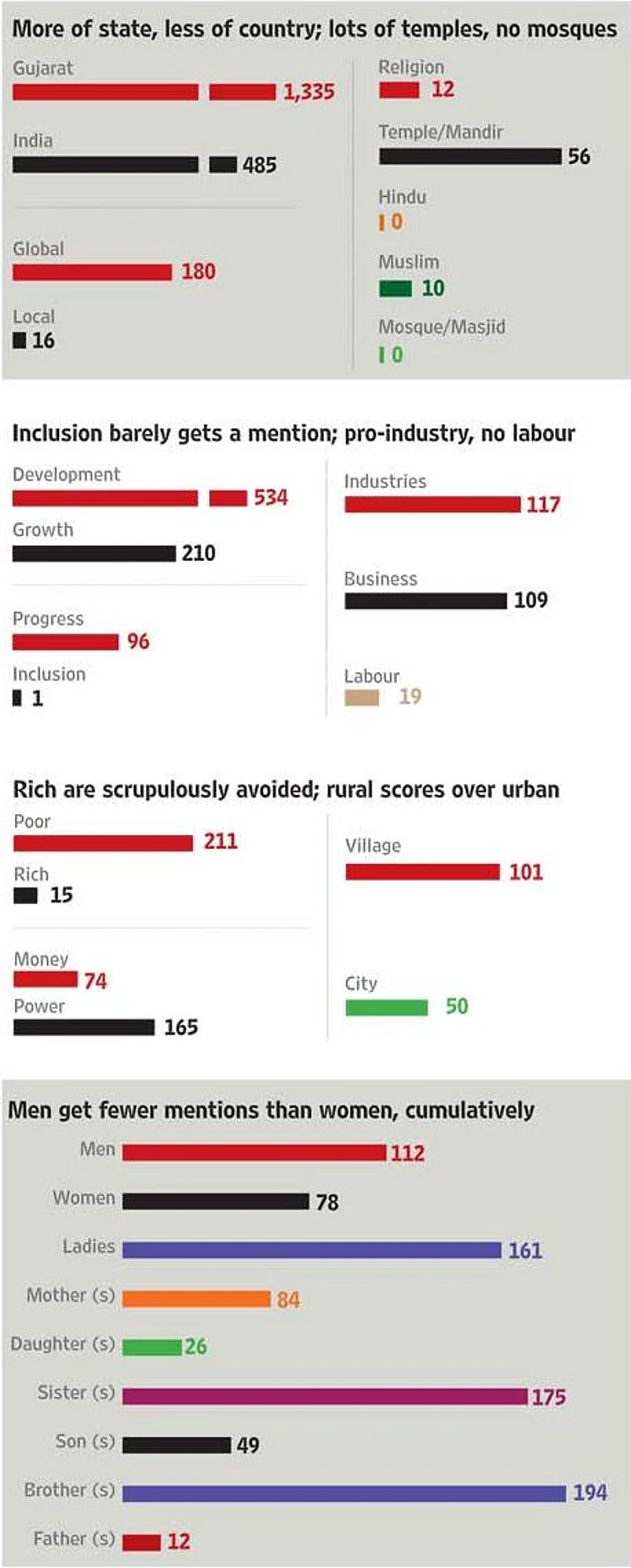

An analysis of 68 speeches translated into English on Modi's website shows how often he uses certain words and themes, and avoids others. He doesn't utter 'Hindu' even once; 'Development' appears 534 times

Language Lessons: In this part of our study, we initiated our enquiries into Modi’s language by downloading a substantialnumber of the speeches over the past two years from his official website this May and undertaking a simple analysis of the main themes repeated therein. Perhaps the single most striking fact we immediately discovered was that the word ‘Hindu’ did not even occur once in all the 290 pages of text we analysed. As we investigated the case of this missing word further, here are just some of the regularities we found. Emergent from the word counts analysed was a strong pattern of contrasts in Modi’s speeches. That is, as our bar-graphs demonstrate, one in every pair of vocabulary items outperforms its counterpart by an extremely significant statistical margin: for example, global versus local; industry/business versus labour; power (not the hydroelectric sort, which we factored out) versus money; youth versus age; poor versus rich; and technology versus the social sciences.

Statistically like the word ‘Hindu’, but perhaps with a different import, the social sciences are conspicuous by their absolute absence in Modi’s discourse. Technology rules. The often remarked on orientation Modi is said to display towards a constituency of technologically driven, globally aspiring youth is quite apparent in these counts. The old are almost invisible but the poor and ‘village’ India do make a strong showing, as do women.

A determined effort to include women is revealed in the bar-graphs on gender. Women, these graphs show, are mostly seen in relational terms (sisters, mothers, daughters) except for the ubiquitous use of the term ‘ladies’, which appears to be a polite way of referring to working women. References to men and brothers, understandably, outnumber ones to women and sisters. To me, perhaps the most interesting feature hidden away in this gender-chart is that sons are mentioned twice as often as daughters.

Other observations arising from these counts concern the social linkages made between region, nation and faith. Here we notice at once that ‘Gujarat’ occurs far more frequently than ‘India’ in Modi’s speeches. Now, this in itself might not be revelatory since many of these speeches were delivered to Gujarati audiences, but it does indicate that ‘India’ is (or was, till now) for the most part refracted through the lens of Gujarat. Indeed, several speeches end with the ringing call ‘Jai Gujarat’—not necessarily extending to ‘Jai Bharat’, as exemplified in Modi’s long speech on Gandhi on May 1, 2010.

In this speech, Gandhi appears, in Modi’s vision, firmly ensconced within a ‘Mahatma Mandir’ in Gandhinagar. Thus, while ‘Hindu’ might have been a missing term, we did discover a significant number of references to temples and mandirs, though none to mosques. Correlating this with other patterns in Modi’s text, however, we found that the crucial Gandhian virtue of tolerance was by far the lowest on the roster of positive emotional attitudes (happiness, hope) alluded to.

Among the ‘negative’ emotions similarly mentioned by Modi, ‘anger’ and ‘fear’ were the most frequent, in contrast to ‘shame’, which occurred only thrice, and ‘guilt’, which like those other missing words ‘Hindu’ and ‘mosque’ did not occur at all. ‘Peace’ often figured as an ideal but so did ‘victory’ and ‘fight’, which notions will soon bring us to the next section of this essay concerning the import of ‘fight or flight’ gestures in the political arena.

Overall, from the evidence of this ‘language’ section, we might argue that the persistent pattern of very extreme contrasts we have found in Modi’s speeches sets up an interesting conceptual tension between opposites and, consequently, as we had hypothesised, a perceived ‘polarisation’. Rather than discursively interpret these rather compelling contrastive results further, let me, then, just point out that they are very likely a strong factor influencing the public impression of Modi as a sublimely focused leader with a singularly prophetic vision about the direction in which he is headed. At the same time, the sharp verbal divergences found in Modi’s speech could indicate a personality unwilling or unable to engage in nuanced dialogue and debate, with a limited and unipolar view of the world.

Genetic Gestures: In the long history of human communication, gesture preceded language by at least 50,000 years. When language developed, this basic non-verbal system continued to support and augment our talk, often revealing the instinctive fight or flight reactions that our more ‘intentional’ spoken words did not. It is the hidden set of relationships between gestures, feelings and worldview that, as mentioned earlier, Darwin put on the research agenda of psychobiology more than a century ago. It has also turned out since Darwin’s time that our brains pay vastly more attention to some parts of our bodies (notably, hands, mouth and eyes) than to others whether we are consciously aware of these effects or not.

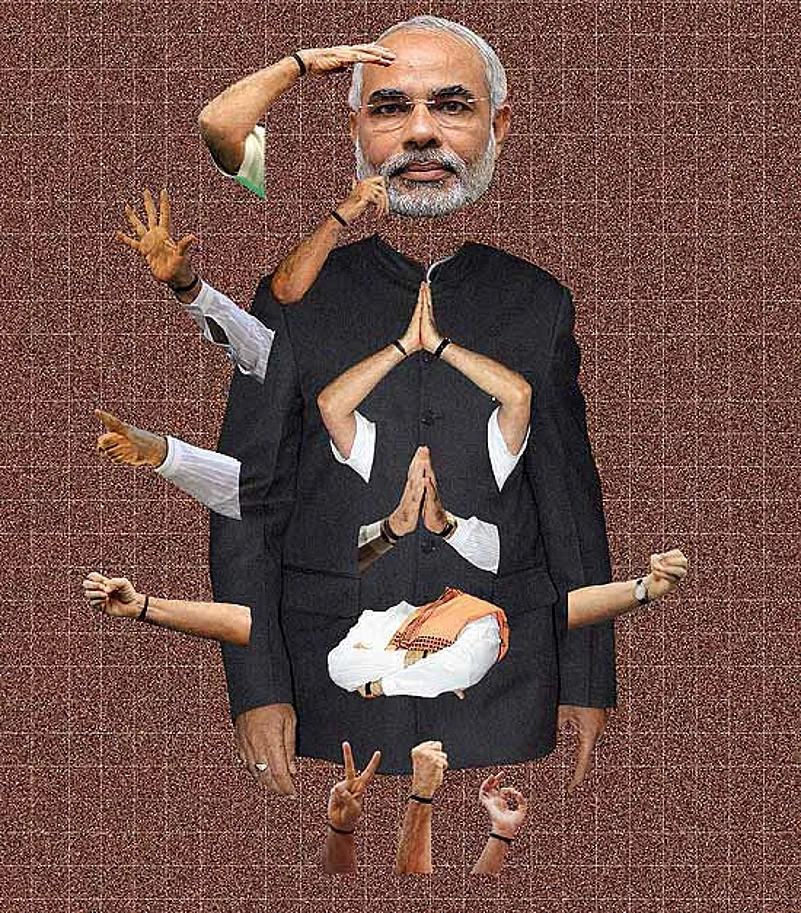

The research for this section of the essay was initiated by first simultaneously downloading over a hundred photographs of Modi and Nitish Kumar in early May. Based on these downloads, we made an initial categorisation of facial expressions and gestures and found startling differences between Modi and Nitish’s physical stances. In terms of facial expressions, Modi displays a very serious demeanour most of the time as opposed to Nitish. His repertoire of gestures is also far more versatile.

Quite remarkably, we found that about 50 per cent of Nitish’s gestures consisted of the open palm gesture, generally associated with a nothing-to-hide or ‘wait’ message. In our data set, Modi uses this gesture only about 12 per cent of the time. Nearly 50 per cent of Modi’s gestures consist, instead, of just two noteworthy indicators: one, the highly assertive upraised finger, routinely interpreted as a domineering fight gesture, and two, the rather ambiguous ‘self-touch’ hand-on-face-or-mouth gesture. This last signal has an unusually high representation amongst Modi’s hand movements and is associated with thoughtfulness and on-the-spot decision-making on the one hand but also with lack of self-confidence and commitment and, sometimes, deception, on the other. The relationship between hand-and-mouth gestures and evolutionary cues has been explicitly made by leading researchers such Michael Corballis in From Hand to Mouth and Susan Goldin-Meadow’s Hearing Gestures. The Nonverbal Dictionary of Gestures, Signs & Body Language (accessible online at the website of the Center for Nonverbal Studies) takes this point further by making a direct connection with displays of political ‘stress’, arguing that “self-touch cues reflect the arousal level of our sympathetic nervous system’s fight-or-flight response. We unconsciously touch our bodies when emotions run high to comfort, relieve, or release stress. Lips are favourite places for fingertips to land and deliver reassuring body contact.”

The ‘social tension’ indicated in our second hypothesis is thus very much in evidence in the photographs we have analysed. While in many respects, Modi conveys the impression of firmly standing his ground and holding his torso and body rock solid, these body stances appear in stark contrast to his expressive ‘hands-on’ talk which can be more or less arranged in a graded series of responses from fight to flight.

Since we found such plausible primary evidence for the classic fight-or-flight responses in our analysis of Modi’s body language, we decided next to test whether audiences perceived these as clearly as we did. Here we designed a series of ‘implicit association tests’ and conducted them in six multiple choice parts that took two or three minutes to complete. These related to a) syllables; b) words; c) sentences; d) speech acts; e) emoticons and f) matching gestures to the politicians who use them.

The basic demographic data (barring names) of our participant volunteers in these tests shows them to be part of that educated, technologically savvy and often young demographic considered an important section of potential Modi-voters. These corroborative surveys again yielded satisfyingly significant results from a statistical point-of-view, showing that our respondents were, by and large, enormously skilled at identifying fight (aggressive) or flight (defensive) gestures, even though they did not know the purpose of our tests and so did not have any inkling about the ‘correct’ answers. Our results suggest that it is quite possible that people are indeed subliminally influenced by a strong ‘fight’ gestural system used by a given politician. However, as mentioned, we also found respondents to be less certain about ‘flee’ gestures, find gestures like the ‘open palm’ ambiguous and often choosing the antonym rather than the target in such cases. In our study, Modi’s were gestures were almost invariably judged to be heavily skewed towards an unambiguous ‘fight’ schema.

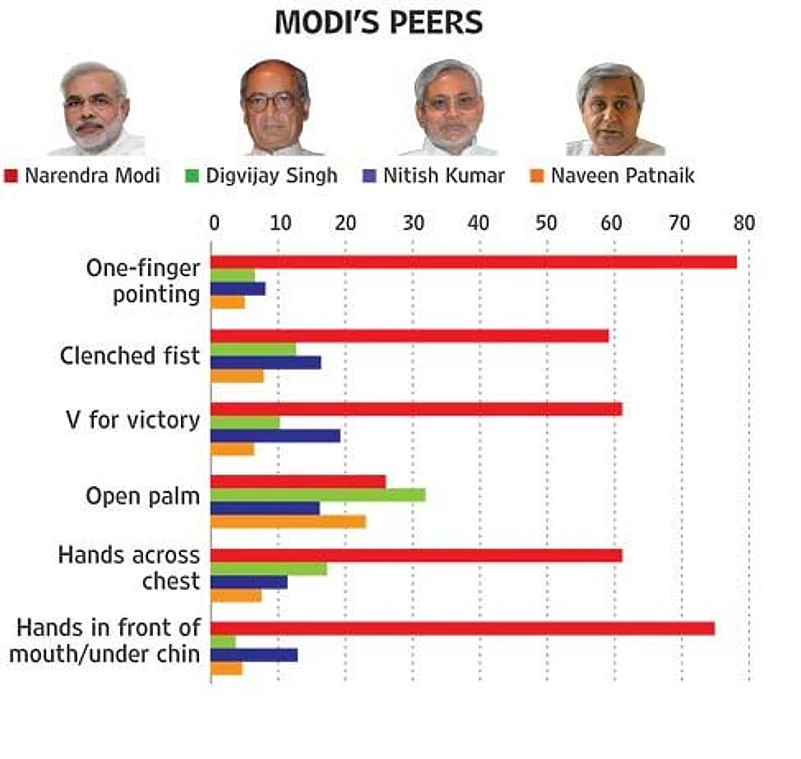

Now, we had found our respondents clearly recognised ‘fight’ gestures, overwhelmingly choosing ‘target’ or ‘close to target’ word-to-image matches when presented with verbal or even ‘emoticon’ multiple choices. So our next set of two somewhat more explicit tests asked people to associate the ‘fight’ and ‘flight’ gestures in our stimuli with fully fleshed-out figures. First, with four present-day politicians (the chief ministers of Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa, all male, all in their 60s and all voted in for at least two terms); and second, we also asked respondents to associate these with four nationally recognised leaders of a bygone era.

As our bar-graph demonstrates, people significantly associate the first three fight gestures with Modi rather than any other politician. Interestingly, the ambiguous ‘hands in front of face’ gesture is also attributed to him, although in this case, we have to record that some participants recognised Modi since his face was partly visible. But this would indicate that they had in fact already noticed that this gesture was characteristically a ‘Modi’ one. In short, whether it is ‘fight’ signal or ‘flight’ (for example, a defensive arms across chest), in general it appears that people pay far more attention to Modi’s body language than to any other current politician.

Now And Then

Modi is more demonstrative but less open. From the old guard, only Sardar Patel comes close

With regard to the association of the fight-or-flight gestures with iconic political leaders of the past (Netaji Subhash Bose, Sardar Patel, Pandit Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi), my hypothesis was that very few of the gestures we studied in today’s politicians would be found during the Gandhi-Nehru era, as the Congress was then unchallenged and the strong regional pulls that we have today were absent. This paucity of peer rivalry would imply that fewer ‘fight’ gestures would be on display then, a hunch that was confirmed when we looked at the archive of photographs of the four chosen politicians from that period.

What is noteworthy is that this lack of visual evidence nevertheless does not appear in the least to prevent people from constructing a persuasive narrative of ‘strong’ (fight) and ‘weak’ (flight) gestures which they associate with national leaderships, past and present. This lends considerable credence to our basic hypothesis that language and gesture powerfully intertwine to influence our political allegiances and the choices we make, or, to put it more bluntly, how we vote. The next section and final section is on the narrative ‘performativity’, surely an essential an element of political success.

Formative Performatives: From Sigmund Freud to Erik Erikson to Slavoj Zizek, psychoanalysts have all repeated in one way or another Wordsworth’s haunting slogan that “the child is father of the man”. This may be true but recovering the formative psyche persona of a political leader is no mean challenge. In Modi’s case, we have only a few photographs and even fewer introspective accounts in the public domain recording his youth for us. Yet, the little that we do have speaks for itself.

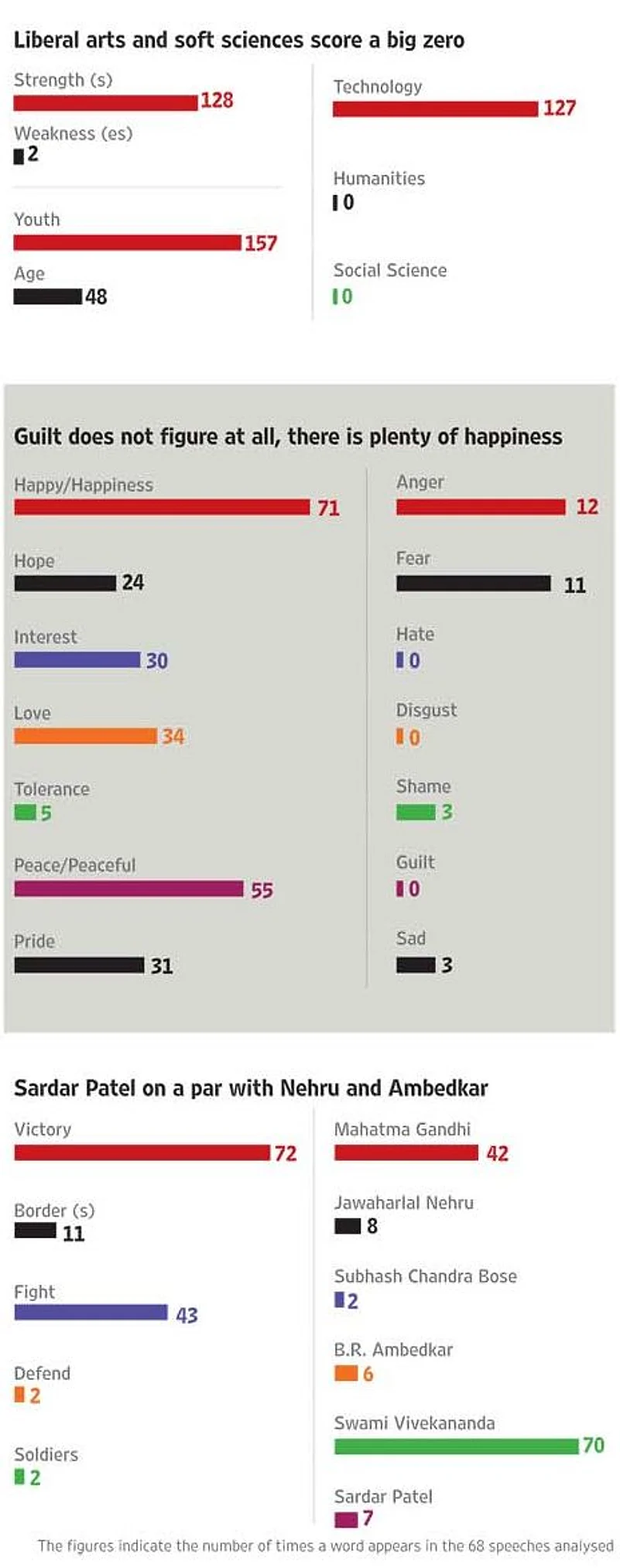

This section introduces us to an earnest boy in a home-guard uniform; a student assaying the part of a brave Kathiawar chieftain in a school play; a young man with his hand upraised in a characteristic debating gesture and, finally, a full-bearded visage that it is hard not to describe as brooding. How do we read these ‘actorly’ images? In this last section, we return to our third hypothesis that the performative dimensions of both language and gesture are likely to be significantly enhanced in the political arena. We also seek to relate this theory to our second hypothesis, outlined in the previous section, that any political ‘action’ is inherently stressful as the political actor is always under surveillance, his ‘image’ being online and on screen 24x7.

Modi has of course been emphatic on the matter in his much-cited interview with Karan Thapar: “I have not spent a single minute on my image...I am dedicated to Gujarat. I never talk about my image.” Now, the second and third of these declarations may well be true, but the first is more problematic. We are told that, like the nationalist leaders of old, Modi has niftily designed his own self-identifying brand of garment, the popular Modi kurta with workmanlike cut-off sleeves. His choice of the symbolic nationalist colours saffron and white, with only a hint of greens is also evident from his photographs and his penchant for flamboyant turbans would not escape being dubbed as grand and showy plumage displays by some evolutionary biologists.

Prima facie, it would not, therefore, be entirely odd to suggest that Modi is, at least subconsciously, aware of the impression he makes. Returning to Modi’s childhood, one of the few on-record incidents from this period informs us that he volunteered “to serve soldiers in transit at railway stations” during the Indo-Pak war. Whether this anecdote is true or merely the stuff of political legend, let us try and decode this remembered gesture. Whom was the Lion of Gujarat moved to serve in his formative years? Answer: Soldiers. We could well, were we to go by this evidence, suggest that Modi’s key emphasis on ‘strong’ leadership cannot be read separately from this early internalisation of external threat, the body-politic now requiring soldier-like responses from Modi the political general in his ‘campaigns’.

Like Sergius, the soldier hero of George Bernard Shaw’s classic play Arms and the Man, Modi famously engages neither in guilt-trips nor apologies, often using language that borders deliciously on the prototype melodramatic dialogue in his interviews: “Look at the written evidence. Has anything been proven against me? Hang me if you find such evidence!” There is more than a hint of a fight reaction in the use of such violent language, but we note, in passing, that the main battlefield in which Modi actually displays flight reactions also happens to be the televised interview, where he has sometimes terminated the talk when pushed. In his play, Shaw deliberately mocks Sergius for folding his arms in the ‘defensive’ manner that we have noted in our study and endlessly repeating the stock phrase, “I never apologise.” However, the difference between Sergius and Modi is major: the one is a just figure in a stage play while the other is a flesh-and-blood personage of awesome power and performative talent. Here is one last experiment we conducted relating to putative ‘performance stress’ in Modi’s interviews.

We have long known in body language research that the left and right side of our faces tell different stories. The right side of our faces, all our faces, is the more social side, the actor’s side, if you like, while the left side is the less-socialised truth-telling side. In moments of stress, these two parts produce increasingly divergent narratives. The power of the proscenium play and the key constellations in Modi’s semantic universe thus could come together very interestingly in a face-reading exercise.

When President Bill Clinton was questioned about Monica Lewinsky, the two sides of his face, experts alleged, showed very different emotions. Such ‘tests’ are of course not admissible as legal evidence, but they do tell gripping Rashomon tales. And, broadly, make certain patterns. We used five micro-expressions from Modi’s TV interviews questioning him over the 2002 carnage in Gujarat. We then asked respondents to identify separately the ‘half-face’ expressions shown by Modi. Some did complain that this test did not ‘make any sense’ since they were only shown a randomised half-face. Despite this, the results were both ‘dramatically’ and statistically significant.

The respondents who participated in this test unambiguously identified anger as the dominant emotion on the ‘truthful’ left side of Modi’s face while ‘happiness’ and ‘surprise’ were the emotions shown on the socialised side. This was a consistent and significant statistical difference and actually correlates with the linguistic word count bar-graphs shown earlier where ‘anger’ was again the most mentioned emotion. In general, negative and positive emotions are very distinctly identifiable on two different sides of Modi’s face during these tense moments.

In conclusion, we must acknowledge that the results of this small study are not conclusive. They are, rather, suggestive. Bar-graphs and pie-charts are reductive devices that capture just part of a much more complex narrative. Considerations of space and limitations of language (we only studied Modi’s speeches in translation) did not allow for a subtler grammatical analysis. Modi’s speeches abound in word-play (‘life/file’), acronyms (eg STCs standing for ‘Superior Technology Centres’, PPPs etc), one-liners, jokes and anecdotes. He is quite obviously a prestidigitator with language and, like all professional magicians, ready to ally with virtual technology to create stage effects in which doubt is out and contradictions banished. Does he succeed in this effort? What accounts for his enormous attraction for urban youth and his party cadre, even as he continues to fuel grave suspicion and opprobrium in others? Why does he hold the media in such complete thrall, generating pop-tags like “game-changer” by the minute despite his chequered past? I hope that we have generated some interest in our attempt to answer this complicated set of questions in ways that relate to the Innere Sprache of our existence as well as to all-too-pervasive realpolitik.

By Rukmini Bhaya Nair with Dr Snehlata Jaswal, Ashish Ranjan and Adarsh Prasad.

(Rukmini Bhaya Nair, well-known critic and writer, is a professor at the department of humanities and social sciences, IIT-Delhi. The views expressed are her own.)