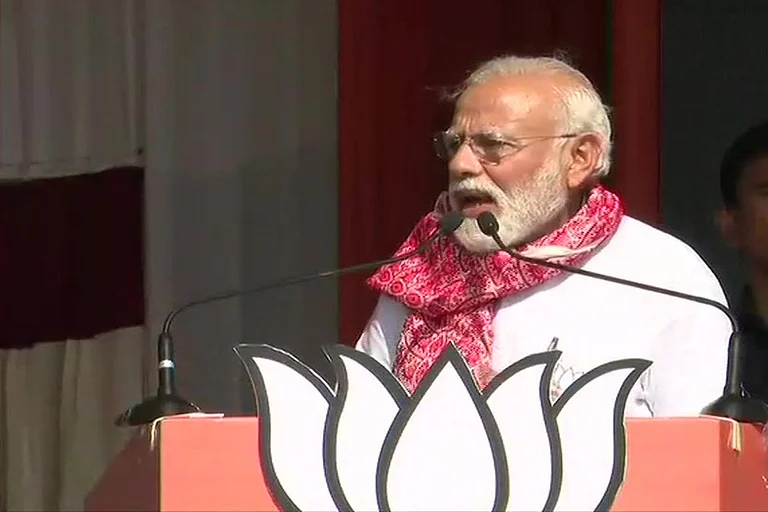

In May 2023, NDTV, one of India’s leading TV news channels, broadcast a documentary series titled ‘9 Years of PM Modi,’ in both English and Hindi. The docuseries covered a range of topics, from diplomacy and women empowerment to infrastructure development, peace and prosperity in Jammu and Kashmir and digital India. The tone was eulogising. The announcement said, “the series captures his (Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s) contribution to shaping the India story.”

It showed how “women empowerment became a hallmark of PM Modi’s governance” and “welfare schemes have been a hallmark of his administration.” Modi’s appeal asking people to visit Kashmir “appears to have had a profound impact” in increasing tourist footfall, showed the episode on Jammu and Kashmir.

There was no critical voice. Without the logo of the channel, it would have been difficult to tell whether it was a promotional series produced by the government or a media docuseries. Although all the episodes featured beneficiaries of welfare schemes and experts praising schemes and policies, the central figure was Modi—no other person in the government or administration mattered.

In May last year, CNN-News 18, too, streamed a show “Nine Years of PM Modi: A Look at India’s Meteoric Rise.” It featured pro-government experts describing how Modi has “made India a key stakeholder in global affairs.” Modi was described as “a strong leader who is confident in the presence of some of the most powerful leaders in the world.”

After Modi’s recent visit to Lakshadweep, India Today presenter Shiv Aroor, while commenting on Modi’s photos released by the government, said: “The pictures are absolutely magnificent. They show a solitary Modi on a beautiful beach. The colours of these untouched tropical islands are bursting out of every frame,” Aroor said. “Modi’s little adventures sound to me as a new dawn for the island transformed cleanly and responsibly into a tourist paradise,” gushed the anchor.

He then drew a parallel between Modi’s visit and former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s 1988 family vacation in Lakshadweep. The latter, in Aroor’s words, involved “a huge official entourage,” and “lavish arrangements”, which “probably was par for the course in the easy-going 1980s but unthinkable in an age of political propriety.”

Since he was drawing a comparison, it was expected that he would also provide information about the number of government officials, including photographers and videographers, who accompanied PM Modi. But no such information was provided. Aroor concluded: “If there is one thing Modi knows, it’s not just the power of pictures, but the power of narratives and things coming full circle.”

According to him, while “the first family of the Congress party” saw Lakshadweep as “nothing more than a place to holiday” and allegedly used state machinery and the Navy’s aircraft carriers, “Modi likes to project himself as a solitary force, focussed on helping the island and introducing Indians to such far-flung territories.”

While Aroor’s viewers must have become accustomed to his unadulterated adulation for Modi, he perhaps struck the right journalistic chord when he said: “Modi likes to project himself as a solitary force.”

Modi is almost always seen alone in photographs—meditating in a cave in the Himalayas, feeding cows and peacocks at his residence, on a shikara in Dal Lake, or inaugurating India’s longest bridge in Assam.

“Nothing can symbolise the Modi regime better than the daily photographs in which he is shown alone, whether it is inaugurating development projects, public monuments, riding public transport or visiting places,” wrote Nissim Mannathukkaren, a professor at the Department of International Development Studies in Canada’s Dalhousie University, in a 2019 article. “There is nothing sad about this wilfully embraced loneliness of Modi. It is supposed to be a sage-like detachment, all in the cause of the nation,” Mannathukkaren wrote.

This is what the media also does—Modi is given undivided attention but not when the BJP or the government has suffered a setback.

Modi is always seen alone in photographs—meditating in a cave in the Himalayas, feeding cows and peacocks at his residence, on a boat in Dal Lake, or inaugurating India’s longest bridge in Assam.

As early as in July 2013—10 months before Modi was sworn in as the Prime Minister—columnist Suvojit Chattopadhyay pointed at the growing media hyperbole surrounding Modi. “The corporate world’s love for Modi, mirrored by the media’s adulation for him, has boosted his campaign,” he wrote in an article titled ‘The Consequences of Modi-fying Our Political Discourse’.

Since then, Modi has enjoyed the love of the majority of Indian media. When the BJP lost in West Bengal Assembly elections in 2021 and the Karnataka elections in 2023, the majority of India’s mainstream media blamed the BJP’s local organisations. But when the party retained Madhya Pradesh, the credit did not go to the incumbent chief minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan. It was “Modi magic”.

Manisha Pande, the managing editor of Newslaundry, an independent news portal focussing on media critique, says that media has been one of the foremost weapons the Modi government has in its hands. While media partisanship and government interference always existed, the post-2014 days have seen hyper-partisanship, especially in the TV media, the most widespread and loudest of the formats.

According to her, the TV media works in three ways. The first is building the cult of Modi, the second is vilifying key opposition leaders like former Congress president Rahul Gandhi, Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, or West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee, and the third is to vilify anyone opposing the government—from farmers protesting against farm laws to truckers protesting legal changes.

“The first way involves portraying him as a man who works 24x7, does not sleep, has no self-interest; as a world leader who is capable of stopping the war between Ukraine and Russia, and as someone taking India to unprecedented global stature,” says Pande. She points out how the media went agog reporting how Modi fasted before the Ram temple’s inauguration, some going on to claim he was drinking only coconut water and sleeping on the floor.

A joint survey by Lokniti and the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), published in 2023, reported that not just citizens leaning towards the opposition parties, but BJP-leaning citizens too are likely to believe that the news media is too pro-Modi government and anti-opposition in its coverage.

“Over half (51 per cent) of those leaning towards the BJP felt that the media’s portrayal of the Modi government is too favourable,” said the report, titled ‘Media In India: Access, Practices, Concerns and Effects’. It also pointed out that even though the supporters of the BJP are more likely to acknowledge media bias in favour of the Modi government, many of them do not necessarily view it as a bad thing.

According to media trainer and columnist Sambit Pal, one of the parameters of a leader’s success depends on his ability to have full control of any event. Modi has been able to do it by using the media in his favour to build an image of a strong leader.

“With a weak opposition and top industrialists supporting the ruling party, the media couldn’t go the other way. They have fallen for the narrative set by him,” he says. “Modi likes to be photographed alone and the media obliges by keeping only him in the frame to the best of their ability,” adds Pal.

He described how live streaming the images of Modi entering the Ram temple all alone, performing the rituals keeping Mohan Bhagwat and Yogi Adityanath under his shadow, and doing sashthanga pranam (prostrate) in front of the deity, have set, what journalists are calling, the mood of the nation.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

“The blanket media coverage sans any reference to the Babri demolition strengthened the image of an omnipresent supreme leader who is unchallenged by anyone else, not even anyone in his party, and architect of a new India dominated by right-wing majoritarianism,” says Pal.

(This appeared in the print as 'Undiluted Adulation')