Early morning, when Kashmir is cloaked in darkness and its residents are sound asleep, the sound of drums pierces the silence, and a voice cries out: “Waqhtey Sahar!” Sahar's time has come.

These are the Sehar Khans who bang their drums on the streets of Kashmir before sunrise to encourage Muslims in the Valley to wake up for their pre-dawn meal, or sahar, so they can prepare for the hours of fasting that lie ahead during the holy month of Ramzan.

The Islamic month of Ramdhan, which begins with the sighting of the crescent moon, is the ninth month on the lunar calendar. One of the Islam’s five pillars is fasting, which is a key component of Ramzan all across the world.

Throughout the holy month of Ramzan, Kashmiris have practised a centuries-old custom known as Sahar-khwani, or calling for pre-dawn meals.

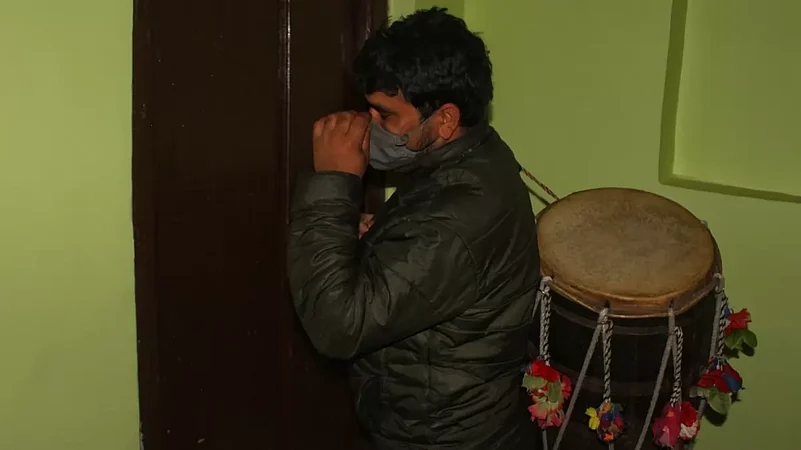

Muhammad Altaf, a Sehar Khan (drummer), starts strolling the streets of Soura Srinagar every night during the holy month of Ramzan to awaken Muslims for dawn meals when the majority of Kashmir is still in a deep sleep.

Every year, Altaf, 27, leaves his home in Aaragam village in the Bandipora region of north Kashmir with his drum and travels 75 km to Srinagar just a few days before the beginning of the holy month of Ramzan.

He wakes people up for sefirah at 3:00 am by strolling through the tight pathways and dark alleyways. “Waqt-e-sahar” (it's time for pre-dawn meals), Altaf yells loudly. As he passes, houses’ lights begin to be switched on. Sehri is typically eaten between 3:45 and 5:00 am in the morning. He travels from one lane to the next while yelling "Waqt-e-sahar" and drumming.

Altaf said, “We work as labourers throughout the rest of the year, and doing this work for the month of Ramzan also gives us a respite from the hard labour work that is tough for us during the month of fasting.”

About 20 years have passed since he first visited Srinagar with his father, who died three years ago. He is not alone in his work. During this period, his 66-year-old uncle, a few relatives, and several neighbours also serve as sahar khans in the city.

Over the years, a few sahar khans, some of whom were from places like Bandipora, have served each neighbourhood in Srinagar. For instance, Ilyas Ahmad, his two sons, and some village neighbours work this way.

For as long as he can, Ilyas wishes to provide assistance to others throughout Ramzan. “More than the little earnings we receive at the end of the month, this brings me satisfaction and sawab (reward),” he said. “People are friendly to us, and we want to keep this tradition alive.”

Khazir Mohammad Gami, 75, a local resident, praises the Sahr Khans as heroes. “The drummers energise and add to the spirit of the holy month. They are an integral part of our rich tradition and enhance the Ramzan experience. I have never in my life missed seeing drummers during the holy month of Ramadan,” said Gami.

Local resident Sajad Ahangar stated, “We value Sehar Khani highly. This has been going on for 400–500 years. The drummers have kept up the routine even in this technologically advanced era, when people can set alarms on their cell phones and mosques have speakers. This is the biggest draw during Ramzan.”

As a result of the availability of modern technology in homes, such as cell phones, alarm clocks, and radios, many young people have begun to underestimate the value and tradition of Sahar Khan, saying that it has become out-of-date.

“Because I have an alarm on my cell phone, I don’t think I need Sahar Khan anymore,” said Haris Khan, a young man from Soura Srinagar.

It is a part of our culture, said Farooqa Gami, 65, a resident of Srinagar, adding, “I still wait for Sahar Khan’s drum beats to wake me up. As I hear those drum beats, it transports me back to my younger years when I used to feel upbeat. These classic drum beaters make it a point to carry on the practise in the age of technology when many people rely on alarm features on various gadgets.”