Everything that surrounded the widow’s home at the end of the village reeked of age-old blankets that had traded their warmth for the scent of smoked meat. There were no flowers that lined her house, no chickens pecked on its grounds, no curtains floated out of windows, no creepers scaled the walls.

She had lived in that old part of the village where the shadows of the forest frequently escaped the shackles of their confines and dropped their curious tentacles over the isolated hut that once brimmed with the pitter-patter of feet and smoke arose in delicate tendrils from the kitchen hearth. She was once the village sweetheart, the only daughter of the mighty village chief who, although rendered limp and partially blind after a fatal encounter with a jackal in the deep trenches of the forest, had tried his best to administer swift justice and ensure that nothing came before adherence to tradition and custom.

It was during his chieftainship that the village experienced unusually bountiful harvests and saw the setting up of the first village church and school where their children were trained to be part of the world out there. By the time he became chief, he identified as a Christian; although, truth be told, he was quite befuddled by the belief system of this new world that spoke a lot about anointing and saving mankind, and, sometimes, he felt quite burdened at the thought of this big mission because, after all, were we not much different from the other creatures. What gave us the right to claim ourselves as the agents of God if we ourselves were so imperfect?

Nevertheless, he had liked that the dictates of this new way of life had ushered in peace among the tribes, and that was why he had turned Christian. He knew that as much a few others resisted entering the new world of the white man, the next generation of his children would all become Christian and by the time they were 7 or 8 years old, they were already exhibiting Christian mannerisms – “Amens” were uttered at dinner time and even young adults started abstaining from consuming soko (rice beer). That was the way of her father’s world.

The widow was nothing like her father. She loved the ways of the Lotha world. It enchanted her, and by the time she was 10, she became quite adept in the knowledge of the many taboos and the pantheon of gods and godlings who moved stealthily among the people. When her father prayed in the name of Jesus, she would not close her eyes or lower her head. Instead, she would sit in defiant stillness until her father would gesture that their meditative hour had come to a close.

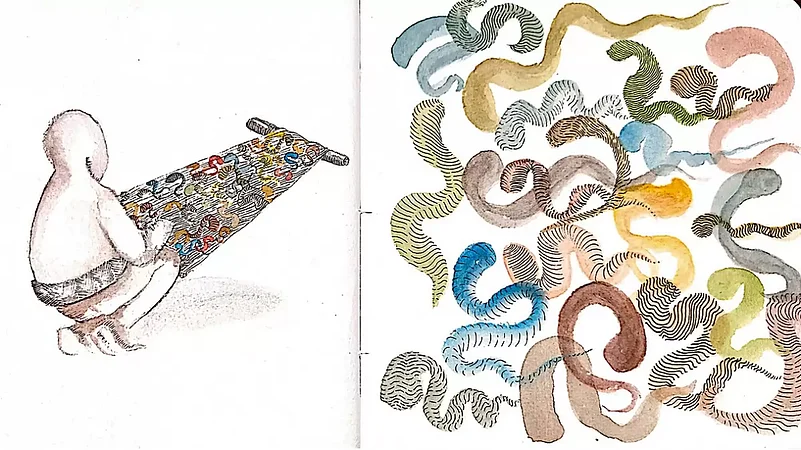

No one imagined she would openly rebel against the village chief who succeeded her father, who, in his turn, in a gesture of goodwill, had gifted the village’s most ornate shawl to the white man who had set up the first school. The shawl had been woven by the women of her family, her late mother and aunt, who had learnt the craft of weaving intricate motifs from their mothers. When she was a little girl, she had asked them why they were so particular about the motifs and the designs, to which her mother had sagaciously explained, “It is because these motifs carried secrets not about themselves, but about life that no human could hold in his tongue.” Her aunt died without ever experiencing the warmth of an occupied womb, and her mother had given birth to an only daughter, and now, she did not have a daughter to pass on this ancient craft.

On the day the new chief was ordained, her family had deemed it fitting to commemorate his new status with the gift of the shawl. It was interlaced with conch shells, and the carvings of the different animals were brocaded in a striking green—an exotic colour difficult to fabricate by even the most adept colourists. The lion spoke to the tiger, the man spoke to the tree. They were there, tangibly solid, awaiting their becoming. And now, the chief had tainted the legacy of their family by according the possession of their sacred heritage to a complete outsider, one who did not understand the ways of their world, who had come and changed everything and was now leaving them with the devices of their own making.

Her heart had raged against this great sacrilege which ultimately led her to the chief’s house. Once there, in the company of others, she had tried to reason with him, and when all else failed, she told him she had put a curse on his legacy. The curse of a widow is a venom. “If you do not take your words back, you will be excommunicated from the village for 20 years,” the chief had thundered. She looked at him with the same stoic resistance that had cast a penumbra over her father’s Christian prayers 20 years ago, and left the village.

For 20 years, she lived in Wokha with her cousins, close to her village. At the end of her exile, lost in the crevices of human memory, she returned to her father’s house to live out the rest of her life.

The Naga sense of belonging is etched in such stories, stories that have come down through generations, conversing with a history that forces us to see a world that no longer exists, complicating our ideas about our world, interrogating our choices and revealing the limits of our official narratives as registers of our past.

By imagining our lost history as a site for engaging in discourse, these oft-forgotten testimonies show us that any reconstruction of the past is intrinsically tied to our present sense of nostalgia for an age before the ravages of modern life. What ultimately matters is how we retell these stories and understand the ways that we remember them, most significantly because they shape the contours of our minds and, consequently, our fates and our futures.

(This appeared in the print edition as "A Sense Of Memory")

(Views expressed are personal)

Beni Sumer Yanthan is a poet, folklorist and assistant professor of English and Cultural Studies at Nagaland University, Kohima