“The myths of a people are a record of their dreams and their sorrows, an inerasable register of their most deeply cherished and highly rated desires and aspirations as well as of the inescapable sadness that is the stuff of life and its local and temporal history.”

Found in “Rama, Krishna and Shiva,” Ram Manohar Lohia’s wild essay from the mid-1950s, these prefatory words clarify the socialist leader’s care for the mythological life of communities before inaugurating a rare, original effort at evolving a civilisational self-portrait as well as a political philosophy through a delineation of the differing personalities of the three gods. A similar aim is pursued elsewhere in his writings via the figures of Draupadi, Sita and Savitri.

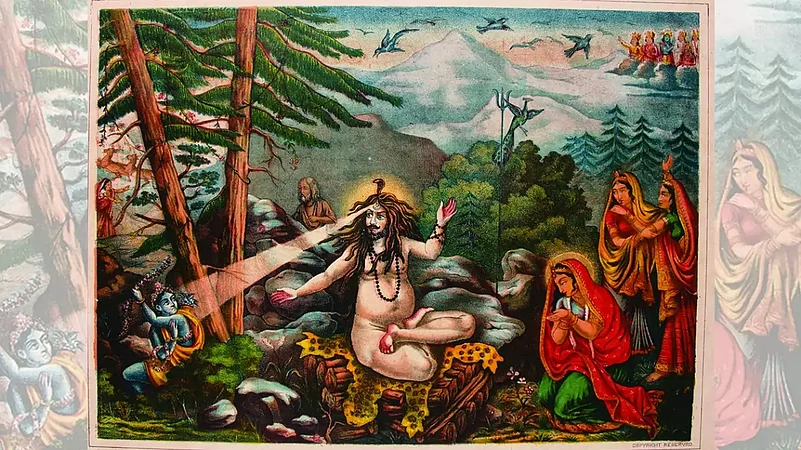

Rama and Krishna, Lohia reminds us, “led human lives,” whereas Shiva was “without birth and without end.” Characterising the formless (nirakara) and attributeless (nirguna) Shiva as ‘non-dimensional’, he points out that he is both infinite and a part of events occurring in time.

The compassionate side of Shiva holds great appeal for Lohia. After destroying Kama for disturbing his meditation, he is moved by Rati’s sorrow at her husband’s death and restores his life. Shiva’s intense love for his wife, Sati (Lohia refers to her as Parvati), also stands out for the socialist thinker. His mourning at the death of his beloved wife takes on a demonic character: placing her corpse over his shoulders, he kept walking until her body fell off part by part across different regions of the country. “No lover, nor god, nor demon, nor human,” Lohia remarks with amazement, “has left such a story of stark and uninhibited companionship.”

Shiva’s actions exemplify Lohia’s principle of immediacy, which asks that moral justifications be found in the immediate steps one has taken, instead of seeking them in either past actions or future outcomes. Taking the morally most appropriate stand in the present without letting the past or the future haunt it, for him, is absolutely essential. Lohia’s discussion of immediacy wishes, of course, to break free from liberal and Marxist utopian projects that justify their political action in the present by alluding to future outcomes as well as the revivalist politics of religious fundamentalists that justify revenge-seeking in contemporary times by referring to actual or imagined deeds in the past.

Holding up Shiva as “the embodiment of the principle of immediacy”, Lohia further notes that he is “not guilty of a single act which can indubitably be described as without justice in itself … Every one of his acts contains its own immediate justification and one does not have to look for an earlier or later act”.

In the famous Puranic episode of the gods and the demons churning the ocean to get nectar, Shiva, who had no part in the war between these two rivals or in their collaborative wish to find immortality through nectar, stepped in to drink the poison emitted from the ocean and saved everyone. His actions, Lohia adds poignantly, “let the story proceed.” Again, when a devotee wanted to offer worship only to Shiva and not to Parvati, his consort, seated beside him, Shiva turned into Ardhanarishvara, part-woman and part-man, in response. If these two episodes reveal for Lohia the exemplary style of Shiva’s moral interventions, two other actions proved less easy for lohia to justify through the principle of immediacy.

When Shiva cut off an elephant’s head to revive the decapitated Ganesha and console his mother, Parvati, didn’t the elephant’s mother suffer from grief? Lohia’s response: “In the new Ganesh, both the elephant and the old Ganesh continued their existence and neither died.” Further, this new being, which meant continued life for both Ganesh and the elephant, went on to prove to be of “perennial delight and wisdom […] which only a comic mixture of man and elephant can be”.

The other difficult episode for Lohia is the dancing match between Shiva and Parvati at Chidambaram. Excelling at dance, Parvati had nearly outdanced Shiva, when the latter raised his leg up high, a move that considerations of modesty made difficult for Parvati to match. Shiva won as a result. Did he lift his leg high merely to defeat Parvati? Or, Lohia wonders further, was his move “the result of a natural crescendo of a dance of life that was warming up step by step?”. Since “The dance of life consists of bumps which a squeamish world calls obscene and against which it tries to protect the modesty of its women” could Shiva have invited Parvati to break the moral limits, in the aesthetics of dance as well as elsewhere?

Lohia stayed an atheist till the end of his life, but his great curiosity about the mythological inheritance of India was firmly in place all along. Unlike other atheists, who prefer either to stay indifferent towards religious symbolism or strive to demystify it or dismiss it as so much irrational cultural baggage, Lohia thoroughly relished it without feeling obliged to believe in it. He sought in it clues to the cultural psychology of Indians. And, in a display of a still-uncommon creative intellectual relationship with the symbolic heritage of the country, he evolved interpretive means from it to aid in the better understanding of Indian society.

Lohia’s engagement with the mythological worlds of non-Hindu faiths and indeed those of Shudra, Dalit and tribal communities was insufficient. One can only wonder about what else he might have offered had this detail been otherwise.

(This appeared in the print edition as "More than a Mythical persona")

(Views expressed are personal)

Chandan Gowda is Ramakrishna Hegde chair professor of decentralisation and development, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore.