‘Make in India’, take a break! While Narendra Modi trots around the globe exhorting the suited-booted people of the business world to use India as a manufacturing hub, China still rules—even when it comes to a project close to the prime minister’s heart. The ‘Statue of Unity’, Modi’s 182-metre tall salute to the Iron Man of India, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, is being smelted and cast into existence not on the soil that was dear to the Sardar—and is, to Chhote Sardar Modi—but has been outsourced to a foundry 96 hours and 6,132 km to the east of Ahmedabad, in the People’s Republic of China.

It will please the Guinness World Records-fixated prime minister that the ‘World’s Tallest Statue’ that was his dream is being poured into shape by 700 workers of the “world’s biggest foundry”, the Jiangxi Tongqing Metal Handicrafts Company, at its 51,000 square metre workshop in Nanchang province in eastern China. Multiple sources have confirmed to Outlook that the Chinese foundry has been assigned the job by Larsen & Toubro, the construction giant which won the Rs 2,989-crore bid to design, build and maintain the structure near the Sardar Sarovar dam.

“The Jiangxi Tongqing foundry,” says Huan Chang, the son of the owner, “is not one of the biggest foundries in the world. It is the biggest foundry in the world. In fact, we were chosen (for the Sardar Patel project) after the project people (L&T) spoke to a lot of other foundries and visited different foundry sites. And we do have previous experience of building similar tall structures in the past as well.” The biggest such project the foundry has executed so far is a 153-metre copper tower for the Tianning Temple in Changzhou.

Way off Ahmedabad-Nanchang: 6,132 km

The tallest statue the foundry has built is a full 101 metres shorter than that of Sardar Patel, but Chang is understandably proud. “We should be, and why not?” he says. “The Statue of Unity is the statue of India’s Iron Man. It’s a good decision to make a sculpture of him.” The foundry’s workers, “the best in the business and specialised in art casting”, are due to complete the statue, which will soar over the 93-metre tall Statue of Liberty off New York City, in a record two and a half years. However, the irony of a ‘Made in China’ stamp on the man who made India is too difficult to miss.

Ram V. Sutar, the 90-year-old Delhi-based designer of the statue, confirms that there will be a Chinese hand in crafting the statue, which Modi said would put not just Gujarat but India on the world map besides boosting tourism in the plains of eastern Gujarat’s Narmada district. He says: “We are at present making a 30-feet bronze statue here in our studio in Noida. The main statue will be made in China and I will go there to supervise it. We are making the prototype and in China they will enlarge it before casting. It will be made in parts and assembled here.”

Surprisingly, or perhaps not, Larsen & Toubro has a slightly different story to tell. A company spokesperson says, “The statue obviously will be built at the site itself at Sadhu Bet (near the Sardar Sarovar Dam). This is not just a statue; it is a memorial. It cannot just be shipped in from somewhere. It will be constructed at workshops which we will create. The foundry and workshops will be created close by.”

When told that perhaps the real statue was being constructed elsewhere, the spokesperson reiterated that it was being constructed at Sadhu Bet itself. But in a written response to Outlook’s detailed questionnaire, Larsen & Toubro said, “All details pertaining to project operations are internal to our company, and are bound by contracts with our clients.” The clients being, of course, the government of Gujarat. The Jiangxi Tongqing foundry won’t reveal how the statue will be shipped to India. Those details, Chang says, are classified. But shipped out in time it will be, he says.

At the moment, though, construction of the statue is in its initial stages in China and casting is yet to be completed. “The alloys need to be prepared as well as the mould for the statue,” says Chang. But it is a race against time even for Chinese foundry, renowned for completion of projects in double-quick time. “Two and a half years isn’t a lot of time, you know, if you consider the fact that the statue of the Standing Buddha in Ushiku, Japan, which is 180 metres high, took seven years to finish,” he says.

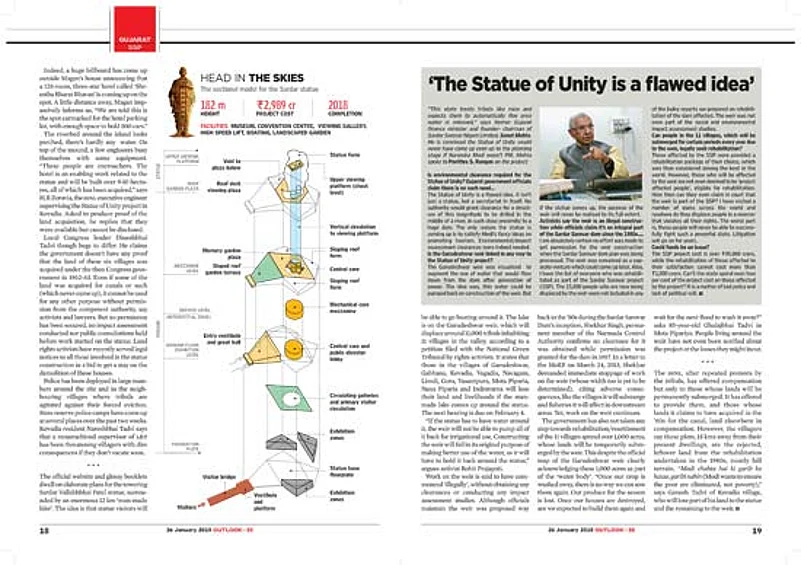

The statue is to be installed by April 2018, nicely timed to be just a year ahead of the Lok Sabha elections. It will be installed at Sadhu Bet, an island 3 km downstream from the Sardar Sarovar Dam. The nearly Rs 3,000-crore project will bring some attention to the culture and economy of the predominantly tribal-dominated Narmada valley, says Modi’s vision document for the project. But an Outlook investigation in January this year found that compensation had not been paid to the tribals who were being forcibly evicted. And an environment impact assessment study has been given the go-by. A recent plea of the local people was thrown out on technical grounds by the National Green Tribunal.

In January, Outlook reported that tribals in Narmada district had not been compensated for land taken away from them.

So how did Sardar Patel’s statue join the ranks of International Yoga Day mats, Ganesha idols, Independence Day flags, Diwali crackers and Benares silks in being made in China? The simple answer is: time and cost. If it was made in India, it would have cost a lot more and taken more time than it does to make in China. The complex answer is: contract. K. Srinivas, member-secretary of the Sardar Vallabhai Patel Rashtriya Ekta Trust, the special purpose vehicle (SPV) set up by the Gujarat government to handle the memorial, says, “This was a global tender and it is the discretion of Larsen & Toubro. As far as we are concerned, the mandate we have given them is that they have to comply with the standards and with local regulations. We have not really specified that they have to procure the raw material only from India. Where they purchase from is not our area.” In other words, ‘Make in India’ was not mandated in the EPC (engineering, procuring and constructing) contract. Larsen & Toubro was free to source material or construction from anywhere in the world.

It is not just Modi’s flagship plan to boost domestic manufacturing that has been turned on Sardar Patel’s head, so to say. There is also the not very small matter of iron procured for the statue of the ‘Loh Purush’. Two years ago, when Modi made an impassioned appeal asking farmers to donate farm implements, the idea was considered brilliant. The iron sent by farmers from India’s six lakh villages would be smelted to construct the statue, a fitting tribute to man who fought for the uplift of the farmer. However, iron from only a third of those six lakh villages (1.67 lakh) could be collected. And, in hindsight, it now appears that the quality of the iron wasn’t good enough for the purposes of the statue. Nevertheless, the collected iron has been handed over to Larsen & Toubro. “It will be used where it is possible. It is their discretion but they will use it,” says Srinivas. Not only is the quality of the iron not good enough but Modi, while announcing the idea, forgot the little detail that the statue would actually be made of steel and bronze.

In other words, to quote again from Larsen & Toubro’s response to Outlook: “Few projects in recent memory have been the subject of such curiosity as the Statue of Unity. Such is the level of interest in the enterprise that anything even remotely connected with the project makes national news.... There also exist structures which were born out of an individual need of the mighty and the powerful of the day to make emphatic declarations of personal beliefs.” Only, in this case, the personal beliefs will be shipped in from China, come 2018.