The Silent Forest Valley

The hooting of owls and howling of jackals in the dead of night. The perpetual fear of encountering bears. The 100-year-old walnut tree—“where the djinns live”—swaying eerily on a full moon night. The deafening silence post-sunset. The breathtaking but melancholic forest valley. The hailstorms. The nail-biting cold. The Himalayan peaks. An incredibly beautiful village named Breswana. Extremely warm villagers. A school on the mountain. Innocent children. A life-altering experience.

The year was 2017—two years before Jammu and Kashmir’s fate changed. When I chose to be a volunteer-teacher at Haji Public School in Doda, the most common reaction was: “Why go all the way to Kashmir to teach Muslim kids?” But the decision was made.

On an August afternoon, I was dropped at Prem Nagar. There were no motorable roads to reach Breswana where the school was situated at an altitude of 7,500 feet. I was told two horses would take me and my luggage up. The swollen Chenab River was flowing on the right. Prem Nagar village was on the left. As we started ascending, the village and the Chenab disappeared. No sign of humanity; just mountains, trees, valleys, fresh-water springs and silence. After a couple of hours, I reached Breswana, just after the Maghrib prayers.

I was in a “conflict zone”. But what I experienced here was a strange kind of silence—within and outside. The kind of silence that makes you calm but also makes you angry.

First-gen Schoolchildren

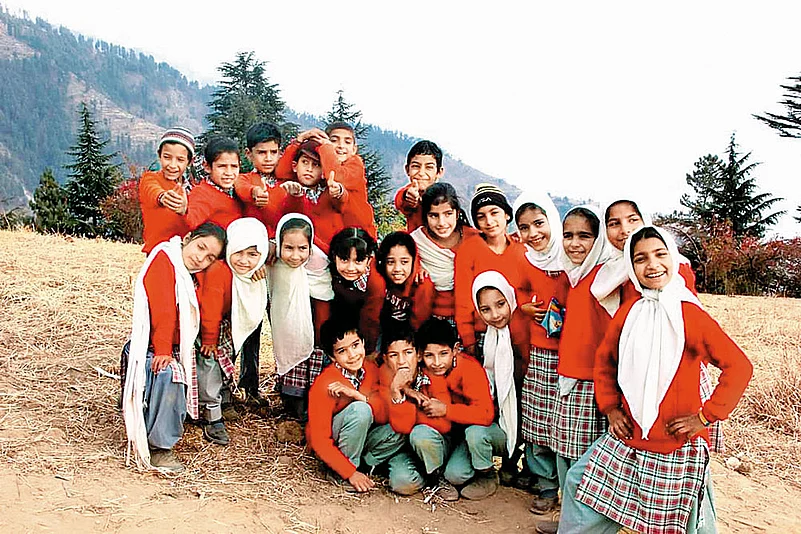

I had never been a teacher and my students were first-generation schoolchildren. On my first day, I was made the class teacher of Class 2. I was nervous. But when 23 adorable children greeted me in a lyrical “gooood mooorning maaaam”, my heart melted. In addition, I also had to teach Math and Science to Class 1 and Class 3.

The challenges were enormous. The village was their world. Very few had been to Doda or Jammu, never beyond. Most had not seen a car or a bus or a train. They didn’t know fruits like mangoes or grapes existed. For them, eating fruits meant plucking apricots, apples and plums from trees. Meals used to be mostly makke ki roti, aloo, leafy vegetables and rajma. But occasions like Eid or weddings were reserved for sumptuous spreads.

Daily, children living in small villages spread across the mountains had to walk an average one-two hours one way, uphill or downhill, through treacherous mountainous terrain and the forest to come to the school. These mountains were their homes. I would show them videos on my tiny mobile screen, of the world beyond, and they would watch with their mouths wide open. Due to the lack of exposure or any sort of technological intervention, like mobiles or TVs, their worldview was limited.

They loved to sing and play. I taught them songs, including an English song on climate change, and a Bollywood tongue twister. They were quick learners, bright and brilliant. They were good at sports. Their daily struggle to reach school made them strong and athletic. If trained well, they could compete on the world stage. They were as good as city kids. But they were stuck. It broke my heart.

Conflict and Kindness

Most were children of farmers. Many spent long durations away from their fathers who had migrated. The incomes were limited, which reflected in their lunch boxes and clothes. But they were large-hearted. They would bring walnuts and apples for me. When it got too cold and I did not have gloves, they would rub my palms with their tiny hands.

They were too young to understand the complexities of the region, but even the adults in the village were silent. No questions were asked; personal or political. All they offered was kahwa, noon chai, naan and warm salaam-alaikums. No discrimination, no biases, no Hindu-Muslim. They said you have come from Mumbai to teach our children, we are grateful. Yet, when my student from Class 2 once jokingly said, ‘bada hoke bum banaunga”, it made me think. Conflict, after all, has a strange way of seeping into psyches and young minds are the most vulnerable.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Every night, while looking outside my window, staring at the silent forest valley, I would think about my 23 children, about what the future might bring for them. Very few students could afford to move out of the village after completing Class 8. I often wondered where these kids would be after a decade. A teacher should not have favourites, but I had—Bilal, Ishtiaq and Sumeera. While bidding adieu to these kids on an unusually cold December morning, a tear rolled down, but my heart wished the best for them. Still does. After all, navigating lives in a conflict zone is not easy.

Swati Subhedar is Assistant Editor, Outlook

(This appeared in the print as 'Doda Diary')