I was in a long-distance relationship last year with a man claiming his ‘long, broken,’ 24-year-old marriage ‘was over’. He constantly referred to his wife as ‘ex’, while occupying the same suburban London home, co-parenting their autistic daughter, and our relationship ended a day before our one year anniversary. It was just the kind of complicated affair that being single in one’s mid-forties one desperately hopes to avoid that wound up on a cruel, one-sided voice note sent in the middle of my night (“I am now going for an office dinner,” it winds up, matter-of-factly), barely three weeks after a holiday in Thailand, as I writhe in bed, battling a complicated chest infection contracted from him on the same trip. My eyelids are heavy from steroids. My auto-immune, fibromyalgia, is through the roof. Everything is in pain. Everything feels broken…

I don’t know why I think of Baba again that morning.

Replaying the audio, my fingers trembling, devastated by the finality, sitting on the pot, warm tears streaming down my face and neck and melting into my bosom. I sob violently as I pee, breathing with difficulty. My left lung is not the same after the deadly second wave of Covid 19 wrecked my system, post a three-week haul in a faceless, overcrowded HDU unit of a private hospital in Kolkata—the city of my birth. Around me, the all-pervasive stench of death and disinfectants and stretchers and ambulance sirens, return to haunt me.

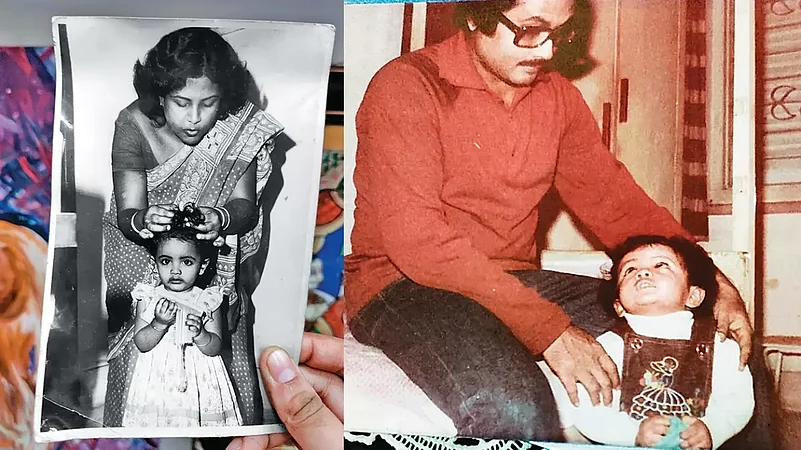

I was four when my biological father, Basudev Kundu, a promising young banker, an alumnus of Presidency College, which is where he met Ma, Sushmita, ‘Mita’, shot himself, a year into treatment for schizophrenia—after he arrived one night, visibly distraught at my maternal grandparents’ South Kolkata residence—my parents were estranged by then and living apart. Ma walked out of their marital home with an asthmatic toddler, huddled on a cycle rickshaw, she stood with no luggage, as her ageing, heart patient father, peered from a first-floor balcony, taking in an only daughter who had married against her mother’s wishes.

Baba’s first attempt at killing himself was probably when he was a boy—Ma spotted marks on his wrist and hands—that he always defended as injuries sustained having fallen down while climbing trees in their Midnapore home. My father was raised in a district in West Bengal. The youngest of two brothers.

Ma, along with my maternal grandparents, never told me of Baba’s long- standing battle with clinical depression or the fact that he’d shot himself in his parental home using a fully loaded gun on a visit there, despite my maternal grandfather warning his parents, on a trunk call that though Baba was much better and in remission —he should not be triggered at any cost. No sharp instruments could be stored at home.

It was Lakshmi Puja that year—a festival that has since then been erased from our family almanac—along with all his physical traces. I remember the first time Ma told me about Baba’s indiscretion, a couple of years ago, sans preparation or permission—as suddenly as her first cousin, a friendly Mama had blurted the truth about his looming absence, that I had used my imagination to make up for, a day before my class ten Boards in 1994.

I had listened to the word ‘suicide,’ for the first time, then aged 16, without batting an eyelid. I had not cried, either. But, I stayed up all night—as the rage filled me up—waking, after an hour of tossing restlessly and tearing up handwritten letters I had spent almost my entire childhood writing, that almost always began with ‘‘Dear Baba’’. As I ripped out page after page from diaries with frayed, yellowing edges, I felt more and more hatred.

I had no idea really why I was angry—instead of being just sad or plain devastated. Why I didn’t rush to my mother, instead of bottling up the betrayal—along with a sense of being deceived and abandoned? Maybe, Ma was the only person I had. My father’s family, his older brother, an absentee uncle, had washed their hands off us. I had no idea that the source of my seething resentment was probably not so much Baba, a man I had no physical memories of, but maybe, Ma to begin with, along with Mamma and Bapi (my maternal grandparents) and Shanti Mashi (my Santhal, childhood nanny) and Kalipada Mama (our Odia man Friday) and Mrs Wilde (my nursery school teacher)—as she pointed to a sunny sky and lied that my father was a star now.

Probably struggling with everyone I ever met—before and after who had actively participated in this conspiracy of silence to cover up and possibly hoped to ease the blow to a daughter that her father is long dead, that he chose to take his own life. Death has no vocabulary in Indian families habituated to celebrating funerals with as much fanfare and social and economic pomp as a wedding—how does one mourn an ‘accidental death?’ We are always telling people to fight and never give up in the face of adversity and illness—how can we view death at one’s own hands then as nothing, but an act of cowardice and giving up—instead of the byproduct of a serious and life threatening disease—a cancer of one’s mind, perhaps.

Suicide, despite being decriminalised, still carries with it the veritable stigma of being viewed as a crime—which is why we commonly use the word ‘committed’, as one looks for someone to blame, almost at once—‘abetment’.

That night, one of the most complex and emotionally traumatic—I despised myself in equal measure—the fat, fatherless, bucktoothed girl in a posh, all-girls convent, lying compulsively to escape being bullied by classmates, who no boy ever liked back, winning at everything—medals in academics and school fests, acing extracurricular activities like singing, dancing, debate and theatre—but perennially a runner-up in love—who struggled to be accepted as herself. Body shamed, dreading another rejection.

Why love from the opposite sex always felt so distant and difficult. Like questions in school, such as, ‘‘So, who do you look like? Mom or Dad?’’ or ‘‘What does your father do?’’ or later, and when my mother remarried when I was 13, ‘‘So, how did your own father die?’’

Last year on his 73rd birthday eve on 18 November, I remember telling my partner how I had only known of his birthday via an old friend, who now lived in Delhi, when I wrote in, telling him I wanted to celebrate Baba’s 70th, as recent as in 2019, a year after I had performed his funeral at a Buddhist monastery, on the morning of my own 40th birthday. A decision I grappled with and even hid from Ma that chilly winter morning—unsure of how she would react to me forgiving Baba after harbouring almost three decades of pent-up and unprocessed emotional debris—of relating my romantic rejections and feeling physically ugly, inwardly, blaming it all on a missing father who I surmised did not love me and Ma enough. And before that, before my uncle’s disclosure, how I’d built him up as a sort of infallible God/superhero, even praying to him each night, asking him for silly wishes to be granted—every time, I mourned another relationship turning to ashes—I was transported back to the same feelings of unworthiness.

In the absence of any form of trauma counselling or support group, I lacked healthy coping mechanisms and was still grappling with acceptance. My primary lens to Baba’s life, his failings in their marriage and his illness, was via Ma’s tumultuous and unhealed emotional lens–the times, I played part therapist, part parent to a grieving woman who had not even been allowed to attend the last rites of her deceased husband–despite being a fulltime caregiver, despite taking him for treatment, daily and dutifully, accompanied by a sick father, who slept at night on the floor, guarding Baba, in a house where there were no chitkanis and locks, bathing him, helping him into pyjamas without drawstrings and keeping me away–always scared. Always on the edge. Always worried.

Every survivor carries scars that may never heal fully.

Was I like Baba?

My greatest fear. The times, I was sad and struggled with happiness–the times I corrected those who remarked I resembled Ma, childishly insisting, I looked like my Baba. Desperately wanting a piece of my father, somewhere. A part of him that would never leave. That would always say goodbye and that he was coming back soon. Return with gifts and stories, like other fathers. The kinds who never break a promise.

‘‘I am not good with all this stuff…’’ my partner had mouthed awkwardly, using the word ‘limitation,’ a term he used a lot, having forgotten Baba’s birthday, hung over as he was after a night of wild partying at his Oxford University, MBA reunion, held after every five years. He had gone alone, last year. I was unusually silent on our perfunctory WhatsApp call– sandwiched on the weekend, between his gym, grocery shopping, dropping daughter off to drama class and household chores–mostly in his car. It was not a video call, thankfully.

I wanted to tell him I was bereft and heartbroken and rudderless–I missed knowing his birthday for decades or imagining what they may look and feel like and celebrating it with him–that I wanted him to celebrate mine on 14 December. I needed support on days like this. Birthdays of a parent who die by suicide are overwhelming, to say the least, even as my partner matter-of-factly resorted to the usual hurtful cliches of me needing to ‘‘move on and let go and normalise a day like today.’’

Suicide grief remains an intensely isolating experience. There is also no bereavement dictionary or etiquette–everyone grieves on their own timeline and at their own pace. As a survivor and now having publicly acknowledged that I belong to a survivor family, I recognise how Ma and her parents and me and mine–have never had any formal acknowledgment of our lived trauma, followed by social ostracisation and judgement, familial exclusion and a crying need to be supported compassionately, instead of how we survived, by simply finding ways to escape the anguish and live on, respectfully.

I don’t know why my thoughts travelled back to Baba’s birthday.

How alone I had felt–staring at an empty screen, again and again and again. Wanting so bad to reach out. But, hoping I did not have to and was reached out to, instead. Wanting to make sense of why every year and especially on this day–and in the weeks before and after, I am swept away.

Maybe, what every survivor needs is attention and an apology of sorts, even if it were from someone else.

‘‘I am sorry for your loss…’’

‘‘What do you need today?’’

‘‘I promise not to leave your side.’’

‘‘Tell me what you are feeling…’’

‘‘How can I show up in a way that you feel most supported?’’

The morning my year-long relationship came crashing down on me, I found myself constantly replaying Ma’s confession about Baba’s indiscretion.

I want to save my mother.

I want to save Baba.

And, myself…

Sreemoyee Piu Kundu is an author and columnist

(This appeared in the print as 'The Deepest Cut')