Things tend to move swiftly in Kashmir. Yet sometimes, very little really changes.

Take, for example, perspectives on laws and troop deployments, which have shifted significantly in just a few months.

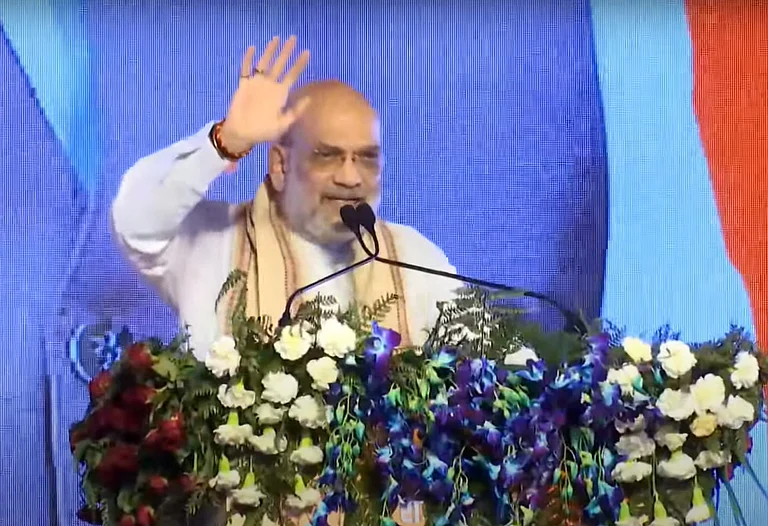

Recently, Union Home Minister Amit Shah sparked debate in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) by suggesting that the central government was planning to revoke the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), a move met with both hope and scepticism by the region’s political parties.

But there was an unstated post-script to Shah’s announcement. The J&K government is now considering using an old, archaic law called the Enemy Agents Ordinance (EAO) to deal with those aiding foreign militants. The law mandates either life imprisonment or death as punishment.

The Enemy Agents Ordinance (EAO), dates back to 1947 and was promulgated by the last autocratic Dogra Maharaja of Kashmir, Hari Singh, following a tribal invasion at the time.

Its preamble reflects the contingencies of that era: “Whereas an emergency has arisen as a result of wanton attack by outside raiders and enemies of the State, which makes it necessary to provide for the trial and punishment of enemy agents and persons committing certain offences with intent to aid the enemy.”

Under Section 3 of the EAO, the penalty for aiding the enemy is either life imprisonment or death, or rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to 10 years. The section reads, “Whoever is an enemy agent or, with intent to aid the enemy, does, or attempts or conspires with any other person to do any act which is designed or likely to give assistance to the military or air operations of the enemy, or to impede the military or air operations of Indian forces, or to endanger life, or is guilty of incendiarism, shall be punishable with death or rigorous imprisonment for life, or with rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to 10 years, and shall also be liable to fine.”

Under Section 17 of the same law, any person who discloses or publishes any information with respect to any proceedings or any person proceeded against under this Ordinance shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to two years, or with a fine, or with both.

Lawyers say that without prior permission from the government, no one is authorised to publish any information about a person booked under the law.

On June 24, the police announced that they would deal with those aiding militants under the stricter EAO. “Under the Enemy Agents Ordinance, the punishment is either life imprisonment or death; there are no other options,” Director General of Police J&K, R. R. Swain said at a media briefing.

Between June 9 and 12, four militancy-related incidents in the Reasi, Doda and Kathua districts of hilly Jammu claimed the lives of ten people, including seven pilgrims returning from the Shiv Khori temple and a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) jawan and left many others injured.

“We are actively considering that such terror attacks be investigated by professional agencies like the NIA (National Investigation Agency) and State Investigating Agency. Those involved in aiding and abetting these attacks will be treated as enemy agents under the Enemy Agents Ordinance,” the DG said.

In J&K’s Department of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affair’s website, the EAO is listed in the section for state/UT acts at serial number 23. Section 1 of the law states that it extends to the whole of the [Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir] and applies also to subjects and servants of the [Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir] outside the [Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir] wherever they may be.

According to Section 4, “offences triable under this Ordinance,” the law states that any offence punishable under Section 3 committed at any time after October 22, 1947, whether committed before or after the commencement of this Ordinance, shall be triable under the provisions of this Ordinance.

According to Section 5 of the EAO, the government has the power to appoint a special judge, in consultation with the High Court, to try matters under the EAO.

The law was adopted by J&K state after 1947. On August 5, 2019, after the abrogation, over 800 central and J&K laws were adapted and extended to J&K. Despite the government stating that the abrogation of Article 370 ensured the “removal of unjust laws,” the Centre chose to retain laws like the Public Safety Act (PSA) and the EAO.

According to a senior police official, recent militant attacks necessitated invoking the EAO. While the Advocate General of J&K, DC Raina, refused to comment on the Ordinance, calling it a sensitive issue, a senior police official said laws like the PSA and EAO were retained after the abrogation of Article 370 because they are “good laws.”

Former District and Sessions Judge Subash Gupta (retired), who frequently lectures police personnel on legal matters, says the EAO in its current form is unlikely to withstand legal scrutiny. To understand why, Gupta says there is need for a closer examination of Section 2 of the ordinance.

Section 2(a) of the EAO defines an "enemy" as any person directly or indirectly participating in or assisting the "campaign recently undertaken by raiders from outside in subverting the [Government of the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir] established by law." Section 2(b) defines an "enemy agent" as someone not operating as a member of an enemy armed force but who is employed by, works for, or acts on instructions received from the enemy.

"This language refers to raiders and their supporters from the campaign launched in 1947," Gupta says. "Even Pakistani armed forces are exempted from the definition of 'enemy' in the ordinance, making the law redundant." He says the EAO is applicable only in the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir, excluding Ladakh.

Riyaz Khawar, an advocate with the J&K High Court, says two persons booked under the EAO were banned Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) founder Maqbool Butt and Hashim Qureshi.

Butt was hanged in Delhi's Tihar Jail on February 11, 1984. He was convicted of ambushing Indian security forces in 1966, resulting in the killing of a CID inspector Amar Chand. Convicted under Section 302 of the Ranbir Penal Code and the EAO, he was sentenced to death. However, he escaped to Pakistan in 1966 from jail. In Pakistan, he was accused of masterminding a plane hijacking in 1971. He was released later and arrested on his return to India in 1976. In 1984, the JKLF kidnapped Indian diplomat Ravindra Mhatre in Birmingham, UK, demanding Butt's release. When their demands were unmet, they killed Mhatre, and Butt was hanged in Feb 1984.

On January 30, 1971, Qureshi and his cousin hijacked an Indian Airlines flight to Lahore. In Pakistan, he was sentenced to 19 years for being an Indian spy but was released after nine years. He sought political asylum in the Netherlands.

On December 29, 2000, Qureshi returned to the Valley, where he faced trial for the hijacking case, after being arrested in Delhi. The government appointed the Principal District and Sessions Judge Srinagar as the special judge to hear the case under the Enemy Agents Ordinance. Released on bail a year later, he continues to be tried in the special sessions court in Srinagar.

Despite claiming double jeopardy under Article 20(2) of the Indian Constitution, which prevents a person from being prosecuted and punished for the same offence twice, charges were framed against him under the EAO and other sections of the Ranbir Penal Code.

Judge Gupta argues that these cases are exceptions. "The law was not designed to be extended from 1947 to the present day," he says. "I am not saying don't use it, but amend it to reflect current times," Gupta says.

Advocate Sheikh Shakeel, a lawyer in the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir, says that the EAO has remained in operation over the years and many have been booked under it. He says after the recent attacks in Jammu, the police are considering using it against those whom it considers to be supporting militancy. Shakeel, however, says the law will always be under court scrutiny if implemented due to its strong provisions.

While the EAO has existed for a long time but has never stoked a public debate in J&K despite its strong provisions, in 2015, the J&K assembly rejected a legislator’s proposal to repeal this law. Haq Khan, a PDP minister, justified the law’s retention, stating, “The law was enacted in 1948 to address external intrusions, and we continue to face similar situations in various forms... The necessity of the law persists,” Khan informed the House.

Aditya Gupta, a lawyer and vice president of the youth Peoples Democratic Party (JKPDP), says that rather than using such laws, trust needs to be built with the denizens of the region and a better intelligence network on the ground needs to be established.

“A more effective and credible approach would involve a renewed focus on intelligence policies and their thorough implementation,” he adds. “Strengthening intelligence capabilities, ensuring better coordination among various agencies, and adopting a more nuanced and strategic approach to counter-terrorism could yield more sustainable results,” Gupta says building trust with the local population through development initiatives, dialogue and respect for human rights would help create a more stable and peaceful environment in the region.

Unlike AFSPA and the Public Safety Act, regional parties have opted to remain silent about the EAO. While AFSPA and the release of prisoners remained prime issues during the parliamentary election campaign, Jammu and Kashmir saw another significant development last month: unprecedented queues outside polling booths. The Election Commission of India (ECI) was surprised by the high voter turnout, and on May 27, the ECI described it as “a massive stride for India’s electoral polity,” saying the region achieved its highest voter turnout in 35 years.

Chief Election Commissioner Rajiv Kumar described the poll percentage in J&K as “a testament to the robust democratic spirit and civic engagement of the people in the region.” Elated over the “peaceful conduct of the elections in J&K,” he called the “active participation of the people of J&K a huge positive for the upcoming assembly elections.”

As political parties were hopeful that the dates for state assembly polls would be announced finally after a long delay of eight years, the situation in Jammu abruptly changed as the hilly region faced a series of militant attacks and the government announced the invocation of the EAO, an act with strong overtones, similar to the more recent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

According to a former police official, the EAO is seldom used except in a few cases. He argues that this ordinance from the Maharaja era contradicts the current government's stance on “colonial-era laws.”

He says under laws like the Public Safety Act and the EAO, a person can be detained for years without the prosecution having to produce any evidence. "Here, the process becomes a punishment," he adds.

For the past four years, the BJP celebrates the anniversary of the abrogation of Article 370, which was scrapped on August 5, 2019, as a "historic decision," claiming it ushered in a new era in Jammu and Kashmir. The party argues that this decision has set J&K on a path of peace and development through social and legal reforms, and a vastly improved security scenario.

However, the retired officer says there is a contradiction in the BJP's stance on peace in J&K and its position on colonial laws. On one hand, they aim to discard old laws as colonial relics starting from July 1, yet they are now considering a law from the Maharaja's era to ensure peace in J&K, which they say was achieved after the abrogation of Article 370. "Have we not moved beyond 1947?" he asks.