The students of secondary and higher secondary levels would soon be able to appear twice for the board exams and be allowed to retain the higher score for further admission. They would even be able to clear some papers on the first chance and the rest on the second, depending on their preparation.

These proposals are among the several key structural changes that have been envisaged by the revised National Curriculum Framework (NCF), released last week by the Union Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan for implementation in the upcoming academic session of 2024-25. In compliance with the National Education Policy (NEP), 2020, NCF also emphasises vernacular languages and interdisciplinary education.

Gone are those days when the fixation with a certain stream would determine the career. If implemented, NCF would offer the students of grades 11-12 the opportunity to choose from a range of subjects across streams -- science, arts and commerce. This gives the students the opportunity to study mathematics, history and accountancy together.

Ministry of Education in its official release also highlighted the flexibility in selecting subjects and noted, “There are no hard separations between academic and vocational subjects, or between science, social science, art, and physical education. Students can choose interesting combinations of subjects for receiving their school-leaving certificates.”

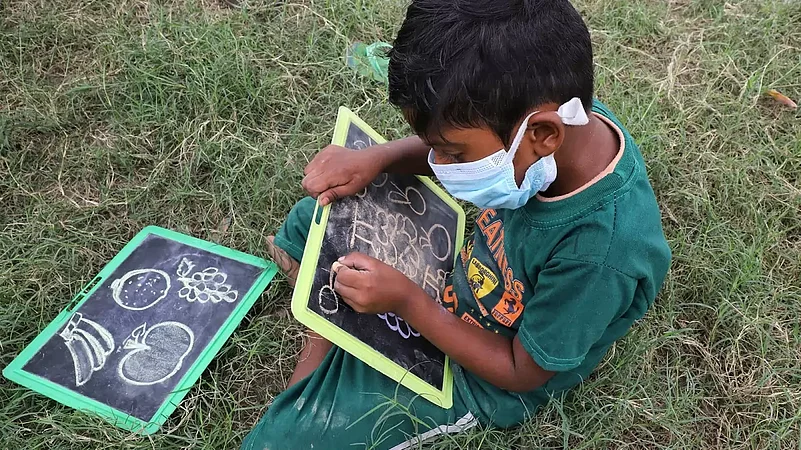

However, does this choice actually exist for the students who study in schools lacking basic infrastructure?

Anita Rampal, former Dean, Faculty of Education Delhi University and chairperson of NCERT Textbook Development Committees under NCF 2005, says, “The whole thing about the choice is quite misleading as it depends on several factors – the school, number of teachers, infrastructure etc. In Delhi which has the smallest number of schools under its government, among about a thousand schools, only about a third offer science.” If this is the situation of the national capital, the condition of other schools would quite understandably be constrained, she adds.

Another study shows that the students in Delhi are given science only when they attain certain marks. “Will the students with lower marks be able to opt for physics, even if she has interests?,” asks a class 9 student from a Delhi government school. “So it seems to be a kind of hook that the middle class might find interesting. But this is applicable to limited students. Some of the elite, private, affluent schools may give them some options,” adds Rampal.

Notably, a study by Education for All in India shows that in 2021-2022, the total number of secondary schools in the country was 276,840 of which only 53.6% i.e. 148,447 had integrated science labs. However, among them, only around 48% of government schools have such facilities.

On the proposal of letting the students appear twice for the board examinations, both the educationists and the students are not sure of the implications. One of the students of a Delhi school, on the condition of anonymity, says, “Don’t you think we will always rush behind board exams to secure higher scores? It would not lessen our burden, rather would increase our anxiety as no good is good enough for further admissions.”

Rampal even points to the possible anxieties among students to score higher marks in the next available chance. Focusing on the administrative difficulties of conducting board exams twice a year, the former Professor of Delhi University says, “On one hand, it will create enormous pressure on the school administrations to conduct exams twice, on the other, it will substantively reduce the teaching hours affecting the completion of syllabus.”

Another pressing concern that questions the feasibility of the board exam itself is the predominance of coaching centres. “There are coaching centres I know that pay a meagre amount to the schools to keep the students enrolled, while they never attend schools in grades 11-12 and spend the whole time preparing for the competitive exams. Students appearing for the medical entrance exam say they work on only three subjects for two years. They take board exams as a formality. Now many are forced to take coaching also for the University common entrance test. For them, how do such efforts matter at all?” asks Rampal.

The NSSO report no. 575, published by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme in 2016 showed 26% of the students i.e. 7.1 crores were taking private coaching. The number must have increased in the following years. As per the study by research agency Credit Rating Information Services of India Limited (CRISIL), by 2021, the business of private coaching that prepares students for entrance exams was projected to stand at a staggering Rs 70,200 crores.

The framework to teach three languages in the secondary stage and two languages in the higher secondary stages, however, is nothing new, feel experts. The southern states have been following the three-language formula for long, notes Rampal. “But it is the northern states that didn’t teach the students any south Indian language,” the scholar laments. The NCF divides school education into four stages -- Foundational, Preparatory, Middle and Secondary. While it recommends teaching two languages in the middle stage (classes 6-8), a supplementary language has to be added in between classes 8-10. Two of the three languages taught must be of Indian origin.

Ministry of Education in its statement, notes, “Given the rich multilingual heritage of India, it expects all students to be proficient in at least three languages, at least two of which are native to India. It expects students to achieve a “literary level” of linguistic capacity in at least one of these Indian languages.”

But do the schools have enough teachers to fulfil the three language requirements?

In March, a parliamentary panel had asked the Ministry of Education to fill the vacancies in the schools to keep up with the NEP’s mandate of a 30:1 student-teacher ratio. The Right to Education (RTE) also has a specified pupil-teacher ratio mandate for grade 1-8. According to the data of the Ministry of Education, around 10 lakh teaching posts in government schools of all categories- elementary, primary, secondary and higher secondary were vacant till December 31, 2022.

Interestingly UNESCO’s Education Report for India, 2021, pointed out that 1.1 lakh schools in India were apparently run by just one teacher. Will these schools be able to implement the three-language requirement or for that matter the interdisciplinary choice-based system?

The questions have also been raised over the delayed inclusion of science and social science. “The draft recommends the introduction of science and social sciences in the middle school after age 11 and this is completely wrong. Children’s concepts develop even before they start speaking. So to say that the concepts develop in the middle school and we don’t need to have primary science and social science in the preparatory stage is extremely questionable,” says the educationist.