“Why, what care I? If thou canst nod, speak too.

If charnel-houses and our graves must send

Those that we bury back, our monuments

Shall be the maws of kites.

—Macbeth to Banquo’s Ghost

When India became a Republic on January 26, 1950, four sculpted Asiatic lions were incorporated into the National Emblem inspired by the Lion Capital of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, who had mounted them on top of the Sarnath pillar in 250 BCE. With a Dharma Chakra in the centre, flanked by a bull and a horse, the National Emblem had “Satyameva Jayate” inscribed on it in Devanagari from the Mundaka Upanishad, which means “Truth Alone Triumphs”.

In 2022, the lions of the National Emblem on top of the new Parliament unveiled by Prime Minister Narendra Modi were more “aggressive” and a controversy about how they looked ensued.

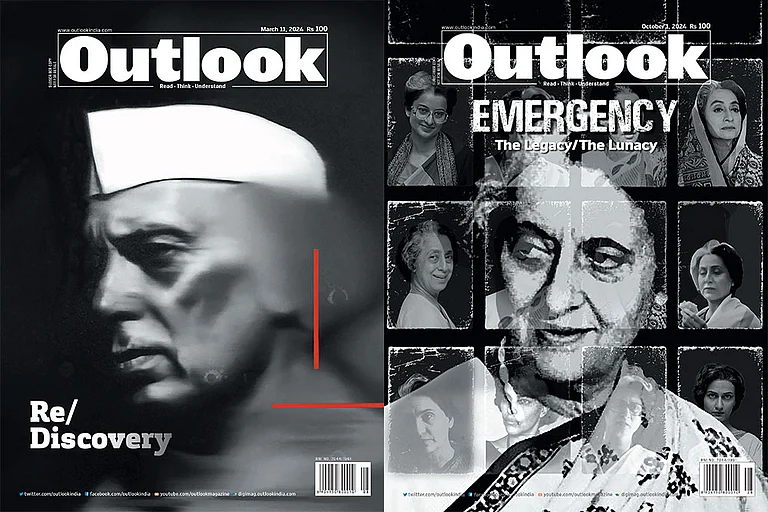

Much has changed since India became an independent country and public discourse about many figures and facts over the years reflect the changing Indian State and social and political environment. India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru remains a controversial figure and like Banquo’s ghost in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, he continues to haunt everyone. Nehru is often criticised for his decisions. He is also hailed as a cosmopolitan and inclusive politician who kept religion out of politics. Sometimes, he is accused of other things like having affairs and sending his linen to Paris for cleaning.

Recently, in his reply to the Motion of Thanks on the President’s address in the Rajya Sabha, Modi read out from a letter by Nehru dated June 27, 1961 and said that Nehru didn’t like reservations in any form. “It shows that Congress has always been against reservation. Nehru ji used to say that if SC/ST/OBC got quotas in jobs, then the standard of government work would fall,” Modi said.

This isn’t the first time Nehru has been invoked in public discourse long after his death. In 2022, on the 75th anniversary of Jammu and Kashmir’s accession to India, Nehru was again invoked. By nullifying Article 370, which had granted the erstwhile State special rights, Modi had corrected those “blunders”.

‘The Fourth World’, an artwork by artist Riyas Komu, captures the state of politics and public discourse in India today. Only three lions meet the eye and the fourth one stands at the back. Komu looks at the disappearing act of the fourth, which vanishes as the sculpture starts to rotate, and says that it signifies the unseen forces that affect everything, which we are unable to control. That’s how the equilibrium is upset.

This issue is a reflection of the state of State, an attempt to make sense of the times.

It was Nehru who had proposed to have the Ashoka Lion Capital represent the sovereignty of the Republic. Nehru had to lead a new country. The world was in a time of crisis. His choice of the National Emblem was based on Ashoka’s commitment to the wheel of law and a recognition of the dignity of all humans. It is this dignity that we have lost. ‘The Fourth World’ also signifies the disappearing act of a free and independent media that is caught in a whirl in a country struggling with identity and other questions.

But all ghosts come to haunt us. Like the ghost of Banquo in Macbeth. All ghosts remind us of follies and virtues.

In a post-truth world of politics, it is a necessary intervention to talk about the good and the bad both and about the context of the times that Nehru belonged to.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Look at the lions. Then and now. Let there be dignity in discourse. Let the fourth estate not vanish and let it stand guard as it is supposed to, check and correct, reflect and remind.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Unseen Lion')