Ayodhya, like an anxious orator, talks in its sleep. After 10 in the night, the town plunges into deep silence. The shopkeepers, hawkers, and devotees have retired for the night; the loudspeakers, pouring out devotional songs, are quiet. But on the main revamped road, the Ram Janmabhoomi Path, the shops’ shutters are wide awake. Wearing a fresh coat of black paint, they display diverse saffron signages: two arrows, a bow, a mace-turned trident, a Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) flag, a crown-wearing Hanuman, and a phrase that showers, sweeps, and cleanses the town, mutating into a greeting, a clarion call, a bhajan, an identity: “Jai Shree Ram”.

Two weeks before the Ram temple’s consecration, Ayodhya resembles an event management firm rushing through last-minute preparations—or a mythological film set under construction. Near its roads, buildings and temples spread soil, sand and stones. JCB machines rumble; cranes and forklifts saunter; construction workers plaster, paint, hammer. Over the last one-and-a-half years, the town has changed so much that several natives say, “It feels like we can’t recognise our own home.”

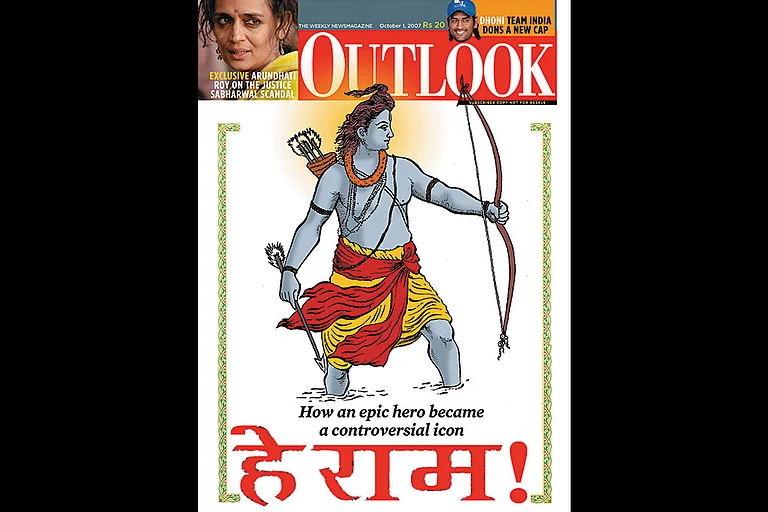

Dualities mark Ayodhya 2.0: what it shows and what it hides; what it was and what it will be. Not too long ago, many devout Hindus harked back to their ‘glorious past’, the Ram rajya, to assuage their anxieties and hone their identities. But now, they can’t wait for the future: Godot will arrive any moment, sitting atop the “sone ki chidiya” flapping her wings. Or take their cynosure—Lord Ram, both an infant (“Ram lalla”), someone to protect; and a warrior, Shri Ram, someone to pray to. Or the town’s architecture: The divider on the Ram Janmabhoomi Path holds elegant lamp posts; the paints pop, the road glows. But if you enter a gulley shooting from the main bazaar, you’ll discover Ayodhya 1.0: crowded, cramped, chaotic. The cars have grown; the lanes have not. If you stay here for long, you’ll see a town drop its mask. A place tired of pretending, posing, posturing.

***

Ayodhya derives its pluralism from Hindu temples and several Jain ones. And then, the mosques, whose exemplar, Babri Masjid, lived for 464 years. More than three decades later, its successor has slunk to a far-flung village, Dhannipur, on the Lucknow-Ayodhya highway, around 22 kilometres away from its original location. Finding it is not easy. It’s not listed on Google Maps; the main road has no guiding boards for the Indo-Islamic Cultural Foundation, the trust managing its construction. Only when you get there do you understand why. The five-acre plot, except for a mazaar, contains nothing. No workers, no bustle, no construction. Not a stone has been laid. If the Ram temple flaunts, then the Muhammad Bin Abdullah Masjid hides, the literal embodiment of a ‘real-estate consolation prize’. Or like Ram banished Sita in the Ramayana, here the Supreme Court, the equivalent of the modern-day rule-making king, has banished a mosque.

***

The shopkeepers on the glitzy Ram Janmabhoomi Path remember not just their former town—“old, dilapidated, congested”—but also their older selves. People who had no say in how their lives would upend. Before the renovation, around a year ago, Awadesh Kumar’s shop and his house where he lived with his family, was 20 feet wide. But then the government widened the road, halved his store, and tossed him a paltry compensation.

Great development erupted great rents. Kumar used to pay Rs 1,000 monthly to his landlord, who hiked it to Rs 5,000. Deepak Rawat too had a shop here for the last 35 years—twelve feet wide, six feet deep. Now? A hole in the wall. He got a lakh, and his landlord increased the rent from Rs 140 to Rs 1,000. The government offered him a six-by-six feet outlet, around two kilometres away, on a 30-year lease for around Rs 10 lakh. He declined. Many shopkeepers had to leave the town. Ayodhya 2.0: where not Lord Ram but his devotees have been exiled.

This story repeats in a depressing loop. Another retailer on the same road had two stores. He lost one; the other shrank in size. For the former, he got Rs 2.5 lakh, and for the latter, one lakh. “No shopkeeper is satisfied,” he sighs. His friend Awadh Bihari, who has a “private job”, says, “Ayodha will become more majestic, more developed, but its residents won’t survive. Ek toh shraap hai Sita-ji ka, aur doosra is sarkar ka [once Sita-ji cursed the people of Ayodhya; now it’s the government].”

“But whether I die or vanish, I’ll still vote for the BJP,” swears the shopkeeper. “I never thought that I’d see something so significant in my life [the Ram temple].” Amid a flurry of complaints against the government, he slips this in: “Vikas is happening. On that there’s no doubt.” Rawat elaborates, “I’ve witnessed what happened in 1992. My friend, Rajendra Dharkar, was shot dead [in the 1990 Ayodhya firing].” Dharkar was a kar sevak just like Rawat and the shopkeeper. They had joined the RSS as adolescents; Rawat rose to become a shakha pramukh. “My grandfather and father couldn’t see the Ram temple,” he says. “Even I didn’t expect to see it. So, as a Sanatani, nothing makes me happier. And no matter how much Ayodhya changes, if something else doesn’t, we’ll be happy: our honour.”

***

Some changes look more incongruous than others. Take Lata Mangeshkar Chowk, half-a-kilometre away from the Sarayu River. It’s the kind of landmark you’d see in Mumbai: Mohammed Rafi Chowk (Bandra), Kaifi Azmi Park (Juhu). But Ayodhya and Lata di? Inaugurated on her 93rd birthday, it contains a 14-tonne, 40-feet veena. But neither the stats nor the statue reveal anything, for this is a Chowk you see with your ears. One song after the other, all dedicated to Lord Ram, sung by Mangeshkar.

Entry to the Chowk is banned. “It was open to the public for the first few months,” says the security guard. “But they trashed it, clicked selfies, and made reels with their girlfriends. Does it suit a religious place like this, which has Saraswati-ji’s veena? So, the government banned everyone from entering.” Just like it banned the sale of liquor and meat in the town.

***

At the Ram Janmabhoomi temple, an ironic and surreal sight greets you—construction workers standing on wooden scaffoldings finishing a metallic roof, busy re-building a once dismantled site. These are the real designers of this movie set: the modern-day kar sevaks wearing “L&T” jackets. L&T (Larsen & Toubro), the multinational conglomerate, is overseeing the temple’s construction and design free of cost. The temple complex comprises two distinct bhakts: the devotees and the corporations; the latter luring the former. Opposite a canopy, Life Insurance Corporation offers free water (and a suggestion: “Keep your family safe with guaranteed income”). So does Punjab National Bank (“PNB Education Loan: Realise all your dreams—interest rate starts at 8.2%”). The trifecta of capitalism, nationalism, and masculinity marks the entire town. Campa Cola (acquired by Reliance Industries Limited in 2022) promises customers “Naye India ka apna thanda”. And in some hoardings, Hanuman has six-pack abs, a brawny God chiselled to perfection.

The Ram temple is closed to the public, but a makeshift devotional area where cameras are forbidden, allows visitors to pray, facing the idols of infant Ram, Laxman, Bharat, and Shatrughan. A Bank of Baroda banner occupies three-fourth of the opposite wall. But the one by Canara Bank catches your attention because it displays an image: Hanuman kneeling in front of Ram accompanied by Laxman and...Sita—the first glimpse of her in this town.

***

If income inequality defines India, then ‘mandir inequality’ defines Ayodhya 2.0. Early in the morning, at the Dhobi temple, there’s no one else except for a priest, Ram Lal Das, blind in the left eye. A curtain covers a room that houses a Ram lalla idol. A student, Hari Om, lives in the temple (which also doubles up as a hostel for the Dhobi caste students). Hoping to become a primary school teacher, he’s enrolled in a local college studying “BTC”. When asked about its full-form; Om smiles, says he doesn’t know. Another temple, Nishad, lies beside a busy road whose main gate is locked; four kids fly kites inside. Less than 100 metres away stands the Maurya temple—cement bags, wooden planks, and scattered pipes litter the floor. Like the Dhobi temple, it functions as a hostel for the Maurya community students.

On the other end of the town lives Shri Pal Das, a priest at the Prajapati temple. Shri mentions the Yadav temple, whose front gate, like Nishad’s, is shut. A few years ago, he says, heavy rains almost demolished it. “Ayodhya didn’t have caste-based temples once, but according to sampradaya [community]”—such as Ranopali, Dashrath Mahal, Badi Chhawni,” Shri explains. “But when the SC and the OBC [Scheduled Caste and Other Backward Caste] people came here, they couldn’t stay the night in the king’s or communities’ temples.” So, long before independence, they built temples for their own castes (and sub-castes), he adds, turning them into assured shelters.

Shri unfurls their list, several on the same road: “Kumhar temple, Vishwakarma temple, Chandrawanshi temple, Pandav temple, Kaurav temple, Bhumihar temple” and, even, “Mishra temple, Chaubey temple, Tiwari temple”. He and his elder brother, Surya Pal Das sip chai and talk. “There has been no change here, except the Ram temple,” says Shri. “The change inside is 0.0.” He discusses the disruption of solace in Ayodhya, its imminent (economic and social) segregations, and the Babri Masjid tussle hinged on the “kabza”, by the Hindus, and the “dhaancha”, of the Muslims.

“Now Ayodhya won’t be a town of devotees but businessmen. It has 1,100 registered temples; in the future, that’ll come down to one.” And all this, Shri adds, is by design. “Because business can thrive in just one place. If it splashes,” he smiles, “the income will shrink.” As plush hotels begin to dominate the area, as the Ram temple complex spawns its own fiscal jungle, as large investments spread and stay, temples like Prajapati, say the brothers, will become rubble under the bulldozer of (uniform and imposed) ‘development’. Or, all mandirs are equal but some mandirs more equal than others. “It’s like someone made Ayodhya drape a jacket of gold but snatched away its soul,” says Surya.

***

Parallel to the mazaar at the plot allotted for the Muhammad Bin Abdullah Masjid, about 30 feet away, a dozen children play a game that seems like cricket. Turns out, it’s “dibbi danda”. A match is underway, where a kid heaves a saffron plastic bat. Sometimes they bet money—“Rs 5, Rs 10”—sometimes play for free. It’s the only thing in this plot that animates with vitality and life. A distant second? A small poster on the mazaar wall displaying the mosque’s model: “A masterpiece in making”.

Back in Ayodhya, less than two kilometres away from the Ram Janmabhoomi temple, is a series of small, dilapidated mosques whose front gates are shut. Noor Masjid is not among them. It is said to be somewhere in the area, but hard to locate. An old woman points to a desolate corner in a field overwhelmed by wild grass and says, “There used to be another mosque there, but it was destroyed last year.” She clarifies, “Not because of any other reason but heavy rains.” Just like the Yadav temple. A young Muslim man says philosophically, “People are people—despite their different religions. When it rains, it drenches us all.”

Turns out, Noor Masjid’s main gate is locked too. Four minarets rise from its roof, and a saffron flag flutters on an adjacent terrace with “Om” written on it. A teenager called Shahrukh Ali, when asked about the other mosques in Ayodhya, is only able to name one. Like the old woman, he mentions the nearby mosque demolished in the rain but doesn’t know much beyond it. Are there other mosque(s) around? “There’s one on the Tedhi Bazaar Chowk, but it’s small.” Does he know a big mosque here? “Big [mosque],” he pauses for a second. “Big mosque—Babri Masjid.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(This appeared in the print as 'Temple Town, Tinseltown')