On December 6, 1992, Babri Masjid was smashed into the earth. ‘Commemoration’—the making of memory—has been an annual ritual thereafter. Media images recall the spectacle of unruly kar sevaks clambering atop the mosque’s domes. The keyword that accompanies the images: demolition. For a modern cataclysmic event, with its own set of mnemonic props, there should really be no room for doubt as to what happened in Ayodhya.

Video: Pragya Singh; Editing: Suraj Wadhwa

But how much does it really resonate in the collective consciousness of the younger generation? The media images and words seek to make that event tangible once again, to create a fresh bookmark in collective memory.

Yet, it’s a hazy message that reaches those born in the 1990s and after. Many in the post-Babri generation believe the mosque is intact, fully or partially. Many do not know there is a makeshift temple on the site now. Here’s a line from one of around 40 people Outlook spoke to, mostly millennial students and professionals too young for direct memories of the demolition. “There’s a mosque there and they want to break it,” says Vishal Sharma, a private airline employee in his 20s.

It isn’t just him. Many of his generation have a vague sense of what happened 25 years ago; only a few recognise an intact Babri Masjid from its photograph—guesses range from “Jama Masjid” to “Wazirpur fort”. A picture of the demolition in progress, though, has higher recall. Abhimanyu, an MA student at Delhi University, comes off better than most. “I know the mosque was a heritage structure and they broke it to the ground probably,” he says, unsure of the extent of damage as he is yet to see a picture of the site after 1992.

Of three commerce students from Meerut, UP, one identifies the unbroken mosque correctly. Then it goes hazy again. “The mosque will have to be broken (to build a temple),” says Akaash. Harinder quips, “Why break it? They can build a temple on its top.”

This isn’t mere ignorance. They have all heard of the Ayodhya movement; they can recognise the keywords—Ramjanmabhoomi, Babri Masjid, demolition—despite their haziness about what happened, even confusion about its location (some said “Gujarat”). This uninformedness leads them to complicated responses on what should happen there in future. Most are conflict-averse, even as they consider Ayodhya a “Hindu-Muslim” matter. To political scientists, these responses are tell-tale signs of the demolition’s biggest impact.

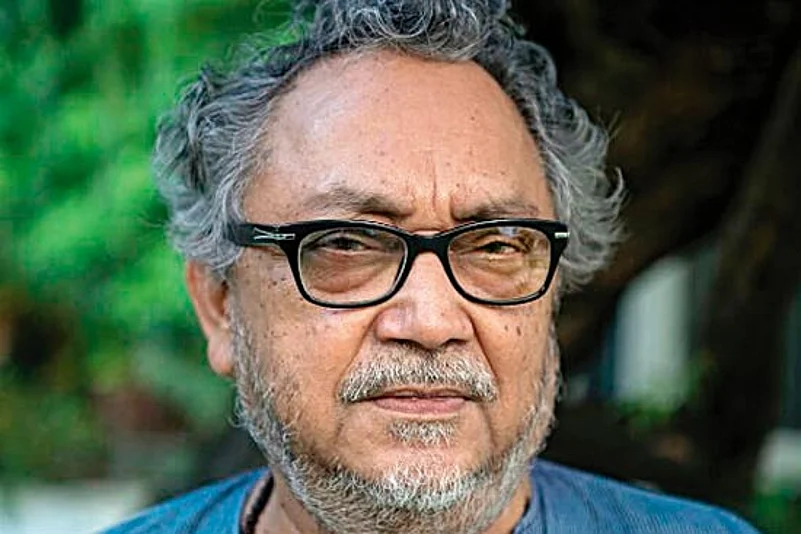

“It solidified the discourse along Hindu-Muslim lines,” says historian Harbans Mukhia. To historians, it’s not evidence but a local tradition since the late 18th century that says the masjid was built over a temple. A Ram temple was wrought into the narrative only later. “If you go and ask people, you find this local tradition has solidified more due to the Ramjanmabhoomi movement,” Mukhia says.

The movement turned a zone of overlaps and blurred lines into a major adversity. “One perception among Indians is that if an aspect of their belief is called ‘myth’, then historians are somehow downgrading their belief to falsehood. The message that mythology and history are two distinct genres of culture is lost,” says Mukhia.

Socio-cultural questions—who gets what, who is neglected, who faces injustice—are more prominent in the Hindu-Muslim divide today than the religious. Instead of abolishing identities, modernisation and democracy multiply them and dull the potential for communal identities. Babri is a civil and legal issue, which some would like to convert into a religious one. But politics is no longer the epicentre of Indian life—people share updates on the market rather than Babri.

For a mobilised mob that sees any history-writing as a ‘rewriting’, to differentiate between myth and history is an insult. “The new insistence on history and mythology thus melded together, with Ram installed as the ruling deity of all Hindus—not just Vaishnavites—is a slow drift towards monotheist elements,” says Mukhia. “Acceptance of difference is a basic theme of Indian culture. Monotheism stresses the equality of all human beings, but it also declares other forms of belief as falsehood, hence there’s a struggle to ensure ‘my’ truth ultimately prevails.”

Hence, the familiarity with keywords that shore up collective recollection of the Ramjanmabhoomi dispute, with no trailing ethical paradigms or conundrums, nor a sense of why December 6 was a turning point. There is talk of ‘sharing’ the site and preference for ‘peaceful resolution’, but not of punishing the vandals, or an apology. “People know a little about what the Babri demolition has done to Muslims, but what it has done to the Hindu psyche hasn’t got much attention,” says Prof Apoorvanand, who teaches Hindi at Delhi University. “I notice a sense of victory in Hindus, but also a certain lack of uprightness. Hindus don’t seem to see what happened as a crime.” For instance, nobody takes responsibility for the mosque’s demolition, the rath yatra or for ‘ek dhakka aur do’.

In the past two decades, privileged castes have come under myriad challenges, from the effects of reservations being felt to the boom-and-bust cycles of the economy—and the younger generation frequently reflects that. One result of this embattled feeling is that your concerns, your faith, is always matched against that of the others. “This new mood, forged after the demolition, has some essential contradictions,” says author-translator Alok Rai. “It’s replete with modernist pretentions, and simultaneously permits the dream of participation in globalisation and the ‘mandir wahin banayenge’ clarion cry. The demolition has created a class of Hindus who are finding it difficult to forgive the workings of time. To expect compassion and recognition of injury is asking too much of them.”

Though both history and the popular tradition trace unclear lines, no party has tried to memorialise the demolition as a challenge to constitutional secularism or the rule of law. It is, instead, memorialised more as a magnet for Muslim votes—essentially reducing Babri to a broad-brush Hindu-Muslim issue. “Such reduction makes it difficult to transmit the real import to future generations,” says Suhas Palshikar, director, Lokniti, and professor of political science at the University of Pune.

No doubt political memory is especially tough to navigate for a generation born after an event, no matter how jarring or extreme. In this vein, the professional middle class largely roots for a 50-50 deal, their idea of “peaceful resolution” is a mosque and a temple side-by-side, or a school, hospital or park at the site—almost never a mosque where once there was one.

“Textbooks avoid ‘controversial’ issues, the media takes many things for granted and the political class, almost conspiratorially, pushes the issue under the carpet,” Palshikar says. Yet, he finds it natural—and reassuring—for ordinary young citizens to pitch for both a mosque and a temple, as many of those surveyed did.

So, how has all this redrawn Hindu identity? The secular-constitutional space has, in a way, formally admitted the assertive Hindu as a category. “The courts have sanctified god Ram’s legal personhood,” recalls Deepak Mehta, head of the sociology department, Shiv Nadar University. “And Muslim radicals say Babri is the most important mosque apparently, but it doesn’t exist. Where does the secular move in this?”

In 25 years, we have been plumbing deeper with every turn of the spiral and forgotten that the dispute, at the core, is about property. The whole idea of introducing god as a legal entity with a claim is ludicrous, but a vast set of literate, middle class people believe it. To expect compassion and recognition of injury from them is asking too much. Babri demolition has created a class of Hindus who find it difficult to forgive the workings of time.

There is an arc that stretches from Ayodhya to the degeneration of secular politics and the creation of an increasingly securitised state, its citizens ever-watchful for strains that deviate from their own. “Babri inserted religiosity as a perfectly normal everyday activity—kanwarias, jagarans, festivals, traffic jams before mosques and temples. Perfectly secular buildings are now seen to be mosques. These are ways in which it changed the fabric of everyday life,” he says.

The deeper effect was on the Hindu-Muslim relationship. While the entire Muslim community has been rendered suspect, and suspicious, a reckless clergy strengthened Hindutva campaigners. Simultaneously, a lack of attention to the meaning and implications of the demolition accompanied a new sense of singular entitlement, a default right of way, among Hindus. What exists today at the site? What is the Ayodhya dispute about? Who are the disputants? The millennials are unable to answer questions like these—some of them basic. But they don’t need to know. The ground under them has shifted already.