The Sangh’s Stolen Child Crusade

How the parivar flouted every law on children to traffic 31 young tribal girls from Assam to Punjab and Gujarat to ‘Hinduise’ them. And how it leaves their parents forlorn.

On June 7, 2015, two days before Babita left for Gujarat, her native Kokrajhar district, in Assam, saw the second showers of the monsoon. It did two things: it accentuated the breathtaking expanse of greenery in her village and forced the khangkrai alari out of their flooded holes in the three bighas of paddy field and farmland her father Theba Basumatary owns, next to their small mud house, in Bamungangaon Bhatipara village.

Six-year-old Babita was always fascinated by these burgundy-coloured, eight-legged crabs. Each monsoon, she would spend hours catching them, putting them in a bamboo basket covered with her mother’s worn dokhana. That evening, Babita demanded khangkrai alari curry. “It’s tedious to catch them, take out their outer shell and legs and cook the edible parts. But I cooked it, thinking who will make it for her in the school hostel,” her mother Champa recalls. Theba, sitting next to her, gets up and walks up to the wall. “Stop discussing all this,” he says to Champa, tears welling up in his eyes.

On June 9, 2015, two days after Babita’s demand for crab curry was met, she and 30 other tribal girls—aged 3-11 years—were made to board a train by two women, Korobi Basumatary and Sandhyaben Tikde, of two Sangh parivar outfits, the Rashtra Sevika Samiti and Sewa Bharati, on the promise of education in Punjab and Gujarat. The girls were from five border districts of Assam, Kokrajhar, Goalpara, Dhubri, Chirang and Bongaigaon. A year has passed since Babita left. The monsoons are back and so are the crabs. In all this time, the girls’ parents haven’t been able to contact them.

In a three-month-long investigation, Outlook accessed government documents to expose how different Sangh outfits trafficked 31 tribal girls as young as three years from tribal areas of Assam to Punjab and Gujarat. Orders to return the children to Assam—including those from the Assam State Commission for the Protection of Child Rights, the Child Welfare Committee, Kokrajhar, the State Child Protection Society, and Childline, Delhi and Patiala—were violated by Sangh-run institutions with the help of the Gujarat and Punjab governments.

Part 1: Baby Snatching

The complexities of the tribals’ animist practices are flattened out for the Sangh parivar’s agenda.

Adha Hasda and Phulmoni, Srimukti’s parents

On September 1, 2010, the Supreme Court of India, dealing with the ‘Exploitation of Children in Orphanages, State of Tamil Nadu vs UoI and Others’ case, concerning large-scale transportation of children from one state to another, said: “The State of Manipur and Assam are directed to ensure that no child below the age of 12 years or those at primary school level are sent outside for pursuing education to other states until further orders.”

This came after a probe into the trafficking of 76 children from Assam and Manipur, most of them minor girls, to “homes” run by Christian missionaries in Tamil Nadu. In spite of this apex court order, according to a CID report from Assam, over 5,000 children have gone missing in 2012-15, and activists are convinced this roughly corresponds to the number of children trafficked on the pretext of education and employment. At least 800 of these children went missing in 2015.

“I never wanted to send my daughter so far. What if she fell sick? What if she needed me? Where will I go looking for her? But this guy forced me,” says Adha Hasda, his eyes bloodshot with anger.

Mangal Mardi, his neighbour and a Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) worker, stood by the barbed-wire fence marking out the small cowdung-plastered patch on which Adha Hasda’s house stood. He got me to meet Adha to hear for myself about the excellent welfare work that the RSS was doing in Bashbari village of Gossaigaon area in Kokrajhar district. Adha’s unexpected outburst has stunned him. He uttered something in Assamese but Adha was undeterred.

“Then where is Srimukti? Tell me? You sent her!” says Adha, breaking down. His wife Phoolmani consoles him.

“Do you plan to send the other three children too, like Srimukti?” I ask.

“No,” he says, looking up in anger. “Not even if they pay me money.”

Mangal smirks at this exchange, kneeling by the pillar of house as he twirls a smartphone in his hand.

Adha, a landless labourer of the Santhal tribe, earns Rs 200 daily. He’s 30, but looks much older. He has four children. His daughter, six-year-old Srimukti, is one of the 31 children trafficked by the Sangh.

“But why did you send her in the first place?” I ask.

“Because he helped me set up home after the 2008 riots,” says Adha. That year, his house was damaged in the Bodo-adivasi conflict. He had to spend a month in a relief camp before Mangal stepped in as an RSS volunteer.

“You are complaining as if I did it for my benefit,” says Mangal. “She has gone to study. Even my daughter is gone.”

“How come you can speak to your daughter on the phone every day and I have not been able to do that in a year?” Adha retorts. “Who knows whether she’s in school or not!”

“This guy has gone mad,” says Mangal, clearly upset, and signals me to walk with him. “You come with me.”

Adha and Mangal’s daughters, Srimukti and Rani, both six, had left together last year for a school in Gujarat. “He told me both of them will be together. But now he says Srimukti is in Punjab and will not come back for the next four years,” says Adha. “What kind of education is this that does not allow parents to meet their children?”

Phoolmani joins him, “Who do we ask now? We only have Mangal’s assurance to continue hoping that she will come back one day.”

Mangal’s house is ten times bigger than Adha Hasda’s. It has a huge compound with neatly planted trees, several rooms, a temple to the left of the entrance and a tulsi plant in a yellow enclosure. A glossy poster of Ram adorns the front wall of the courtyard. Mangal, with a saffron teeka, a red holy thread around his wrist, sits under the poster in a white vest and dhoti. He has stress lines on his sweaty forehead, and is visibly angered by Adha’s flare-up. As I enter, he surreptitiously tries to click my picture on his phone. I catch him in the act and offer to pose. He is taken by surprise. “There have been four such visits in the past to enquire about the girls. I don’t know what is up.”

***

On June 16, 2015, a week after the girls were taken away, the Assam State Commission for the Protection of Child Rights (ASCPCR) wrote a letter (ASCPCR 37/2015/1) to the ADGP, CID, Assam Police, and marked it to the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, calling this incident “against the provision of Juvenile Justice Act 2000” and concluded that it amounts to “child trafficking”. The commission requested the police “to initiate a proper inquiry into the matter and take all necessary steps to bring back all 31 children to Assam for their restoration”. The police was asked to submit an Action Taken Report to the ASCPCR within five days of receipt of the letter. No action was taken; no report was filed; no cognisance was taken by the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, which is monitored by the BJP-ruled Centre.

After the ASCPCR letter to the police and other government bodies, members of the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) of Kokrajhar made several visits to the houses of the trafficked girls.

CWCs are established by state governments, according to mandates of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000 (amended in 2006). Each district-level CWC has the powers of a metropolitan magistrate or a first class judicial magistrate. It can hold people accountable for a child, transfer the case to a different CWC closer to the child’s home, reunite a child with his/her community. Children can be produced before the committee or one of its members by police, public servants, Childline, social workers or public-spirited citizens. A child may present himself/herself before it too. The probation officer for the case is required to submit regular reports on the child. After gathering background information and interviewing the child to understand his/her problems, the committee determines the best interests and safety of the child and may unite him/her with biological or adoptive parents, find a foster home or put him or her under institutional care. The committee is to give final orders on a case within four months of a child being presented before it.

Besides violating the SC guideline of 2010 not to take any child outside Assam and Manipur for any purpose including studies, Sewa Bharati, Vidya Bharati and Rashtra Sevika Samiti also violated the Juvenile Justice Act by not producing the girls before CWCs in Assam or obtaining NOCs from them before taking them away to Gujarat and Punjab.

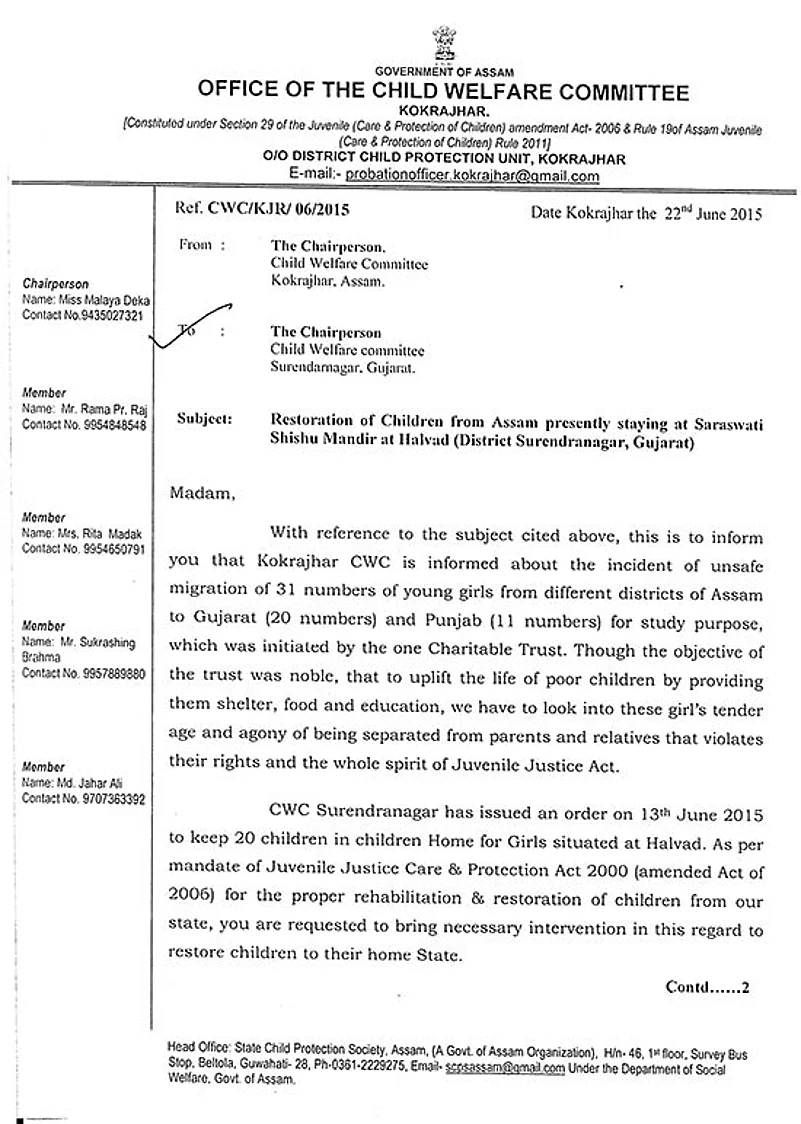

On June 22, 2015, Malaya Deka, the chairperson of CWC, Kokrajhar, wrote a letter(CWC/KJR/06/2015) to the CWC, Surendranagar district, Gujarat, requesting the “restoration of children from Assam staying at Saraswati Shishu Mandir, Halvad, Surendranagar”. The letter says: “...we have to look into these girls’ tender age and agony of being separated from parents and relatives that violates their rights and the whole spirit of Juvenile Justice Act. It will be convenient for you to bring children to Guwahati from where concerned District Child Protection Units will be entrusted to take back children to their families in Kokrajhar.”

Sewa Bharati and Rashtra Sevika Samiti, however, sought to circumvent this by obtaining affidavits from the children’s parents, signed in the presence of a notary public and judicial magistrate in Kokrajhar on July 13, 2015, a month after the girls were taken away. The 31 affidavits give consent to the RSS-affiliated “Shikshika Manglaben Harishbhai Raval Kanyachatralaya/ Vidya Bharati Saulagna Saraswati Shishu Mandir, Surendranagar, Gujarat” to take the girls away for education. Outlook has copies of the affidavits—all in English, signed in English, and identical, while most of the parents Outlook met are either illiterate or don’t know English. Actually, this is what the parents’ affidavits say:

- I am a cultivator and a riot victim.

- My home is totally damage(d) in the riot which occurred on 25th January 2014.

- I still stay in relief camp.

- I don’t have source of income.

- I could not afford the school fees for my daughter.

- So, for better education I am sending my daughter to Gujarat to study in (by) my own will.

Malaya Deka, CWC, Kokrajhar, says, “This in itself is a violation of the law, since the affidavits should have been made before the children were being taken away, not a month later.” The CWC, Kokrajhar, visited the parents of each of these girls to verify the details of the affidavits. The CWC probation officer found that none of these parents were affected in the ‘riots of 2014’ or lived in relief camps. Instead, most of them were landed and had some source of income. The most glaring lie was that the affidavits said the Bodo-adivasi violence took place in January 2014, whereas the incidents date from December 2014.

She says, “In February, 2016, a probationary officer of the CWC was physically threatened by Mangal Mardi. He was told that if he comes to enquire about the children again and meets parents, he will be bashed up.” An FIR was registered against Mangal and a few others in the Gossaigaon police station in Kokrakhar. The probationary officer had confirmed that all the information provided in the affidavits was false. In March 2016, Malaya wrote a letter to the (Gauhati) High Court and the CJM and district sessions judge, Kokrajhar, requesting them to take action against those involved in filing fake affidavits. There was no response.

***

“What’s the problem if a Hindu sends his children to a Hindutva organisation?” Mangal asks me.

“But all adivasis aren’t Hindus,” I say.

Traditionally, Santhals worship Marang Buru (or Bonga) as the supreme deity, and according to their religious view, there is a court of spirits handling different aspects of the world. All through the year, they have rituals connected to the agricultural cycle, besides rituals for birth, marriage and burial at death. They all involve petitions to the spirits and sacrificial offerings, usually of birds.

But Mangal has his own reasoning. “You see, Hinduism is not a religion per se,” he says. “All those who believe in god are Hindus. The world was once inhabited by Hindus.”

Vishwa Hindu Parishad leader Praveen Togadia had said the same thing at a rally in Bhopal on December 22, 2014. He’d said the VHP would go all out to raise the population of Hindus in India from 82 per cent to 100 per cent.

Mangal repeats what Phoolendra Dutta, an RSS worker who has worked in Kokrajhar for 19 years, told me earlier: the RSS tells tribals that anyone who worships the sun, trees, wind and nature is a Hindu. The complexities of the tribals’ animist practices are flattened out for the Sangh parivar’s agenda. Dutta had told me they tell the Santhals and other tribals to plant tulsi as an initiation into Hindutva.

I ask Mangal which gods he speaks of, and he says, “Ram, Durga, Hanuman, Shiva, Tulsi, Bharat Mata.”

Mangal Mardi, Sangh activist, at his Gossaigaon home

“Which god do you believe in?”

“I believe in Ram. But the Bodos believe in Shiva. That is why Bodos and adivasis are different.”

In fact, the original religion of Bodos is Bathouism, which does not have any scriptures, religious books or temples. Bathou, in Bodo language, means the five principles: bar (air), san (sun), ha (earth), or (fire) and okhrang (sky). Their chief deity Bathoubwrai (bwrai meaning elder) is believed to be omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent. The five principles are Bathoubwrai’s creations.

But the Sangh’s neatly articulated difference between Bodos and adivasis is newly engineered to serve their own purpose. The decades-old conflict between Bodos and the Santhals and Mundas in Assam rests on the Bodos being granted Scheduled Tribe status, while the Santhals and Mundas, who have ST status in Jharkhand, Orissa, Bihar and West Bengal, do not have that status in Assam. The explanation cited often is that they were outsiders brought in as tea-garden workers during colonial times and hence cannot be counted as indigenous.

Says a child rights activist who has been repatriating children trafficked from border areas for over 20 years, “In an attempt to get both under the Hindu fold, the Sangh parivar outfits have come up with this convenient divide: Bodos are Shaivites, adivasis are Vaishnavites. This keeps them together as Hindus and also lets them marinate in their old ethnic conflict.”

Mangal has pat answers to all questions. “Since when have you been associated with the Hindutva sangathan, the RSS?” I ask.

“All Hindus are automatically part of it. But I became active in 2003, when Virendra Lashkar, the Kokrajhar zila pracharak of RSS, made us aware of this fact,” he says with a contented smile.

“What do you do as an active member?”

“People are forgetting their sanskaars: rituals, customs and duties. Like each house should have a temple and a tulsi (holy basil) plant. I teach them about their Hindutva identity, the Hindu nation and their duty towards it.”

“What is our duty to the Hindu nation?”

“To save it from Muslims and Christian intruders. Look at what the missionaries and Bangladeshis are doing here.”

“And how does forcefully sending girls to other states help the Hindu nation?”

“It is for their own good. Hindu girls must learn sanskaar. Illiterates like Adha know nothing,” he says, trying to be convincing.

“But why fake documents? And why cannot parents not meet or talk to their daughters?” I press on.

His face is flushed. “I can’t talk to you any more. Ask Korobi.”

Part 2: The Trail

In the border areas of Assam, there’s a comprehensive network of Sangh outfits which concentrate on welfare activities

Ropi, whose daughter Divi is one of the 31 missing kids

Korobi Basumatary, a Bodo activist of the Rashtra Sevika Samiti, began to expand her network days after becoming a pracharika, or full-timer, in 2008. I’d first met her on a December afternoon in 2012 at a Rashtra Sevika Samiti camp in Aurangabad, Maharashtra, to which she had travelled all the way from Kokrajhar. Picked up at an impressionable 20 years of age from a relief camp in 2004, after her house was destroyed and her family scattered in Bodo-Muslim violence, she had committed herself to the Hindutva ideology. It was Sunita, a seasoned pracharika from Maharashtra who had been working in the Northeast for over two decades since the Nellie massacare, who spotted her and took her to a kishori varg, or training camp for young women. Of the passage from trainee to full-timer, or pracharika, Korobi had then told me: “It was like control of destiny—in my hands.”

A pracharika holds a prestigious position in the Hindutva scheme of things. They are well trained in the ideology, as also in paramilitary skills. Like the pracharaks of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, they practise celibacy. The renunciation of the materialistic and sexual aspects of life grants them a special status, the chastity being associated with purity and spirituality. Pracharikas commit themselves for life to work in remote areas, spreading the Sangh parivar’s Hindutva ideology.

“As a Sevika Samiti pracharika, I’ve learnt how to fight for my rights and take what is mine,” I remember her telling me at the camp, her face flushed with blood, the fixation on “revenge” seeming absolute.

Four years on, Korobi, now 32, has been identified by the ASCPCR as one of the main executers—along with Sandhyaben Tikde—who organised the trafficking of the 31 children. Her successful implementation of the Hindutva agenda on the ground is proof of how the Sangh parivar is making a determined play for young girls in the conflict zones of the Northeast, tailoring its siren calls to their vulnerabilities, frustrations and ambitions, and filling the void the State has so far failed to address. Besides, the frequent spurts of inter-ethnic violence in the region have helped their efforts.

As we wait outside Divi Basumatary’s locked house in Malgaon village in Kokrajhar, an irritated voice is heard. “Now who are you? What do you want?” It’s Ropi, thirty-something, slim and athletic, walking up with two buckets of water in her hands and her year-old daughter Arunika sling-tied to her back. I tell her we have come to ask about Divi, her five-year-old daughter—one of the 31 missing children.

“First you took her away, and then all her pictures,” she retorts. “When will she come back?”

“Who took away her pictures?”

“Someone like you,” she says. “I’d called Korobi to ask about Divi; she sent someone who took both pictures I had of her.”

It’s a story the parents of Sarmila, Surgi, Sukurmani and other children among the 31 missing have told me before: after visits from the CWC and the ASCPCR, inquiring about the missing girls, Korobi had sent people to take away all the pictures of the girls from the parents.

“Don’t you have another copy?”

“This village is 40 km from the nearest town,” says Ropi, visibly upset. “We don’t have so many pictures like you people.”

Putting the buckets in a corner, she opens the locked hut. She picks up a stool next to the handloom inside, on which an orange dokhana—a traditional Bodo wraparound for women—is in the process of being woven. Ropi earns from making dokhanas and selling them in the city, while her husband Bakul Basumatary works in a cable factory in Guwahati and visits her every six months.

Bakul is upset with Ropi for having sent Divi away in his absence. “He says we have lost her because of me,” she tells me. Korobi had told her Divi would study in a school and visit her every year. “But it’s been a year since we even spoke to her. Korobi now says Divi will come after three or four years. She has even stopped answering my phone,” says Ropi, breaking down.

Like Ropi, none of the 31 parents have a single official document to prove they handed over their daughters to the Rashtra Sevika Samiti, Vidya Bharati or any communication with the ‘schools’ the children are supposed to be in. With the pictures taken away and no further communication with their handlers, it is difficult for them to launch a search.

“But what made you send your daughter away?” I ask.

“Sewa Bharati,” she replies.

***

In the border areas of Assam, there’s a comprehensive network of Sangh outfits such as Sewa Bharati, which concentrate on welfare activities—medical camps, activity camps and so on. Vidya Bharati and Ekal Vidyalaya concentrate on providing Hindu nationalistic education to children. The Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram and Friends of Tribal Society look into the ‘welfare’ of tribals. The pracharikas make use of these outfits to reach remote areas to spread the Sangh parivar’s Hindutva idealogy.

Sewa Bharati was set up in 1978 by Balasaheb Deoras, the third RSS sarsanghchalak, to focus on marginalised sections of society. The Akhil Bharatiya sahaseva pramukh, or all-India ancillary services chief of the RSS, guides the organisation and it is represented in the Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha, the highest decision-making body of the RSS. That way, Sewa Bharati has an influential place in the array of Sangh parivar outfits. According to the Sewa Bharati website, they run over 1.5 lakh welfare projects in India. They also run hostels for young tribal girls and boys and informal education centres in India.

***

“We had all fallen ill two years back—Divi, my two other children, and me,” says Ropi. “Kanchai, of Sewa Bharati, had organised a medical camp. That’s when we got in touch.”

After the camp wound up, Kanchai started a matrimandli, or committee of mothers, that would meet every week. “We’d sing songs, and Kanchai discussed things like hygiene with us—how to use the toilet, how to make pads at home for use during periods. She was a Bodo, and so it was good to have someone who knew our language and culture telling us all this.”

Simultaneously, Kanchai organised a bal shivir, a three-day camp to teach children ‘sanskaar’ and the importance of becoming good citizens. “That’s when Kanchai asked me to meet Korobi and send Divi to school in Gujarat.”

This is the usual strategy for penetration used by the Sangh. First, the welfare organisations step in. They increase the mass base, identify potential trainees. Small steps like visiting the remotest village, distributing lockets, pamphlets and Hindu literature pave the way for complete penetration. Then, the local Rashtra Sevika Samiti and RSS full-timers follow. The services of Sewa Bharati come especially handy in areas where the State has failed to provide basic amenities to its people. Sewa Bharati acts as a safe front for these activities. Most villagers and parents think that the children have been taken away for education by the NGO Sewa Bharati. The Sangh connection and Hindutva indoctrination is less apparent to a rural person.

Brahma helped the Sangh parivar zero in on needy families

Living and growing up in the conflict areas of Assam rife with incessant Bodo-Muslim or Bodo-adivasi ethnic violence makes people feel strongly about their identity and stick by their own. The possibility of differentiating between right and wrong becomes minuscule. Paranoia takes over, paving the way for Hindutva propaganda.

***

Kanchai Brahma is a 34-year-old activist of Sewa Bharati in Gossaigaon, a small town in Kokrajhar district. Her story has many parallels with that of both Korobi and the 31 girls in question. At age 15, she participated in a kishori varg camp organised by Sewa Bharati in her village Kumursami. “These camps primarily focus on teaching sanskaar to young girls,” she tells me as she clicks my picture in her office.

“What kind of sanskaar?” I ask.

“Girls are told how they have forgotten their culture, where a ‘hello’ has replaced ‘namaskar’ and long pants have taken the place of our traditional dress. All this is because of the influence of Christian lifestyle. They should get back to their culture and become good women of the nation,” she says with a smile.

With such training, the young women grow up with an unquestioning belief in the Hindutva idea of the intended role of women in the Hindu rashtra, as the Outlook article (Jan 28, 2013) on the Aurangabad camp showed. They focus on celebration of folklore, language and history, teaching an anti-Muslim, anti-Christian interpretation of these. Among the Bodos, there’s no scepticism about the Sewa Bharati’s activities because of the stellar reputation women like Kanchai and Korobi, who are from the same community, command and the image of empowerment they project. This girl-power tactic has proved adept at appealing to the parents of small girls who have ambition for their children but no means. It works like a girl-to-girl recruitment strategy.

Kanchai was spotted by a Rashtra Sevika Samiti pracharika at a camp in 2003. In 2004, she was sent off to a hostel in Uttar Pradesh for training, along with three other girls from her district. After a year’s training, she came back in 2005. “In the next two years, we canvassed in three districts—Goalpara, Kokrajhar and Chirang—and told them about the excellent time we had and managed to send 500 girls to that hostel,” says Kanchai. “Over the years, some of them returned and got married. They now work as grahini sevikas, or part-timers.”

Kanchai, of Sewa Bharati

Parents who are not part of Sewa Bharati’s cult activities are treated differently, and the others inform Sangh workers if they were not acting in line. Her conviction evident, Kanchai says, “Bodo people are being fooled by Christians, killed by Muslims. I was trained to save their identity and remind them of their Hindu origins. Since I am a Bodo myself, I joined Sewa Bharati and started working towards the development of Bharat Mata.”

As Kanchai scouts for recruits, a recent addition to her efforts comes from the Sangh parivar’s Ekal Vidyalaya project and the Van Bandhu Parishad. Ekal Vidyalayas are one-teacher schools, essentially non-formal education centres where one teacher takes up to 40 students for three-hour sessions. “They are taught national songs, poems, games. Instead of ‘Ba ba black sheep, have you any wool?’ we teach them ‘Bharat desh, mera desh, meri mata aur pranesh, meri jaan, mere praan, Bharat mata ko qurbaan,” she says.

There’s a focus on choral singing, which fosters a sense of unity, conformity and group identity. Children are taught folk songs, presenting Indian history in line with Hindutva ideology. The girls sing at many festivals and occasions organised by Sewa Bharati, such as medical camps and matri mandalis, and also for public entertainment at special events. It’s a quiet, subtle indoctrination.

The Ekal Vidyalaya Foundation was registered in 2000, though the schools have been functional since 1986. As of 2013, it had a presence in close to 52,000 villages in the tribal belts of India. It is associated with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, a Sangh parivar outfit. In the past, it was headed by Subhash Chandra of Zee News. BJP MP Hema Malini has served as its brand ambassador. According to Phoolendra Dutta, the RSS activist from Kokrajhar, there are over 290 Ekal Vidyalayas in Kokrajhar district alone. The Van Bandhu Parishad helps Ekal Vidyalayas devise a methodology to provide “education with sanskaar to the vanyatries (tribals)”. They support and enhance the curriculum taught in schools: lessons are moulded around the Hindutva understanding of history, biology and geography. The teaching is geared to produce religion-conscious, obedient, self-sacrificing Hindutvavadis. Sewa Bharati, through its kishori and bal vargs, helps in enrolling children in these schools, quietly creating a culture of moral policing and threatening the natural diversity of faith and practices.

“Training girls is most important because they can inculcate values in the entire community in a way that will take years to be corrupted,” says Kanchai. “They can raise families that will be the core of a Hindu rashtra. That is why we especially pay attention to counsel young girls not to use cellphones.”

“How?” I ask, hoping for a different logic from that offered by the khaps of north India in their attempt to rein in young women’s sexuality.

“There is a rule in Hindu religion that one has to marry within our religion,” says Kanchai. “Young girls talk to boys on the phone and then elope to get married. We recently struggled to get a girl to leave the Muslim man she had married. Initially, she refused because she was pregnant but after repeated guidance by us, she left him. We told her how the Muslims had killed Bodo people in the neighbouring villages. She saw reason. She has now separated from her husband and works for Sewa Bharati.”

Both Kanchai and Korobi have turned out to be effective recruiters of young girls for the Sangh outfits. Their insider image in the Bodo community is a strategic plus point. As women, they tend to gain the trust of the local community more easily than men might. The positive representation of their own image and experience at the training camps outside Assam is not only persuasive but also one that young women might aspire for. This inculcates an unquestioning understanding of the role of women as mothers, wives, daughters and radicalises them in the cause of a Hindu rashtra.

Four years after meeting Korobi in the Aurangabad training camp, her phone call to me in the house of one of the missing children’s parents made me notice the change in tenor. That time, she had been firm and polite. Now, she was defensive and rash.

I was in Ghana Kanta Brahma’s house in Daodshri village in Kokrajhar. He had also sent his daughter, Bhumika Brahma, to Gujarat. His house is massive, perhaps one of the largest in the village. As I sat in the courtyard, admiring the wall arts and murals around it, his wife Subhadra brought tambul—betel leaves and areca nut—to welcome me in traditional Assamese fashion.

I was cross-checking the details of the affidavit he had signed to hand over his daughter. Parents of three girls had told me that Brahma had worked as a BJP mobiliser in the recently concluded Assam elections. He had helped Korobi identify these three girls to be sent along with his daughter, just like Mangal Mardi had. Says Dena Tudu, Sukurmani’s father, “He (Brahma) speaks to his daughter almost every day. But we don’t know where he has sent our daughters. He is rich but are poor people meant to give away their children in charity?”

When I ask Brahma why he said in his affidavit that he had no source of income though he owns 20 bighas, he brazens it out with a “Just like that.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning that instead of letting the Muslims and Christians convert people of our community and take away all our land and jobs, I am saving the children with the help of Korobi and RSS and restoring other Bodos to their original identity,” he says.

Sangh workers like Korobi have mastered the art of manipulation. In a conflict-torn area, they work to turn the slightest bit of hearsay into fact, raising suspicions and creating paranoia and anger so that people are unable to think through things clearly. All this serves their agenda. It runs parallel to the Sangh parivar’s ghar wapasi programmes elsewhere. The germinal idea is the same: as the Sangh declares so facilely, all Dalits, tribals and Muslims in India are originally Hindu. When Sangh outfits announced ghar wapasi programmes, pushing through a series of reconversions of Muslims and Buddhists to Hinduism in 2014, an Akhil Bharatiya Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram report stated: “Out of 10 crore tribal population of the country, 1.22 crore have converted to Christianity. The Ashram has approached 53,000 villages and wants to reach out to the remaining 1.09 lakh tribal village by 2015 end.”

I try to confront Brahma to seek a reaction to the dubious practice vis-a-vis children, and ask him, “But why make false documents and lie to other parents? This is illegal.” In response, he animatedly says something in Bodo, which I don’t understand, and takes my picture on his giant-sized smartphone. Before I can make sense of it all, he dials a number and shoves the phone in my hand.

“Hello,” I say.

“Why are you people constantly coming and interrogating these parents? Where were you when the Muslims were ruthlessly killing these people?” shot a voice from the other side in Sanskritised Hindi.

“Who are you? Please introduce yourself,” I request her.

“My name is Korobi. I am not scared of you guys. Go and tell whoever you want, OK?” she says.

“Why don’t you meet me and talk to me about it?” I say.

“I don’t want to meet anyone. You people don’t care about Hindus at all. Hindus, who are the real inhabitants of this country. You are only worried about outsiders like Muslim Bangladeshis. And now you are even spreading rumours about the RSS trafficking children,” she says.

Clearly, she is aware of the official proceedings and police complaints against her and others.

“I never mentioned the RSS or any other organisation. In fact, it is you who is saying it,” I reply.

“When Muslims come and take their jobs, their land, rape their women, then it is the RSS that comes and helps them and not you guys from Delhi,” she continues.

“I am just asking about the whereabouts of the girls. If you have to say anything, please meet me. This way you are disrupting my work,” I say.

“I don’t want to say anything. Just stop talking to the parents. Go to our office in Jhandewalan in Delhi and ask them all these questions.”

She hangs up.

Part 3: Ranis Of Chhota Kashi

The message was clear—that if you’re from Northeast, you are Hindu—and it is being clearly indoctrinated in these young girls

The gateway to Saraswati Shishu Mandir, Halvad

According to the Article 9 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, “Children must not be separated from their parents unless it is in the best interests of the child (for example, in cases of abuse or neglect). A child must be given the chance to express their views when decisions about parental responsibilities are being made. Every child has the right to stay in contact with both parents, unless this might harm them.” India ratified the Convention in 1992.

Now to get to the 31 children from Assam, a letter dated June 16, 2015 (ASCPCR 37/2015/1), from Runumi Gogoi, chairperson of the ASCPCR, to the ADGP, CID, Assam Police, says: “The Childline India Foundation, Central Zone, with the help of informer and anti-human trafficking unit, Crime Branch, GP, and RPF rescued children on June 11, 2015, at about 7.40 pm at New Delhi Railway Station.” It refers to the same 31 children.

The Childline India Foundation (CIF) is the nodal agency of the Union ministry of women and child development, acting as the parent organisation for setting up, managing and monitoring the Childline 1098 service across the country. It is a free, 24-hour emergency phone outreach service for children in need of care and protection. It has set up emergency phonelines for the purpose.

On June 11, Childline Delhi got a call from an informer about the trafficking of these girls on the Poorvottar Sampark Kranti Express. The girls were rescued at Paharganj station in New Delhi. The same day, Shaiju, a coordinator of Childline, wrote to Sushma Vij, chairperson of the Child Welfare Committee in Mayur Vihar, Delhi, informing her that the children, who were accompanied by “a lady called Sandhya from Kokrajhar and Bongaigaon in Assam”, were rescued and taken to the police station for cross-checking their documents. But at this juncture, strangely, an order of the CWC, Surendranagar, intervened and within a day, the girls were sent onward to their destinations from the police station itself—20 to Halvad, Gujarat, and 11 to Patiala. Shaiju wrote, “There is a need to collect more information about these children from the police department of Delhi and concerned CWCs of the aforementioned districts with proper/relevant support documents. I would like to request you to kindly investigate the matter for the best interests of the children.” No action was taken on this request from the CWC, Mayur Vihar, Delhi. Responding to the concerns, the ASCPCR wrote to the ADGP, Assam, on June 16: “The mentioned children were rescued on June 11, 2015, but the written evidence showed that Child Welfare Committee (CWC) (Surendranagar) issued the order to Secretary, Children Home, Halvad, under section 33 (4) of Juvenile Justice Act 2000 on June 3, 2015. Without producing the children before the mentioned CWC, how can they issue order with regard to proper custody of the children in the children’s home situated at Halvad.... How can children of Assam who are with their parents/guardians have previous record, case history, individual care plan in a Child Welfare Committee of Gujarat state?” Outlook has a copy of the letter from the CWC, Surendranagar, that blatantly violates this clause of the Juvenile Justice Act.

The letter from the ASCPCR also directed the Assam police “to initiate a proper enquiry into the matter and take all necessary steps to bring back all 31 children to Assam..... The government of Assam is implementing the Right to Education and other developmental work as well as a protection scheme for children in the state, then why should children go away from their families in the name of better facilities. This is against the best interests of children and against the provision of JJ Act 200. It can in fact be termed as trafficking.”

A day later, on June 17, 2015, the Gujarat Samachar newspaper, Ahmedabad edition, published the following: “Saraswati Shishu Mandir in Halvad, which is affliated to Vidya Bharati Trust, organised a meeting in Delhi, during which it adopted 20 girls who have been orphaned during the recent floods in Assam. This humanitarian move has contributed to enhancing Gujarat’s image and made the state proud. The girls who have been adopted are aged 5-8 years, and a majority of them are totally without any support. The children were received at Delhi railway station by trustees of the Saraswati Shishu Mandir, Mr Ramnikbhai Rabdiya and Ms Varshaben Rathod, as well as two police officers.”

The next day, on June 18, Kumud Kalita, IAS, member-secretary, State Child Protection Society, Assam, wrote to the CWCs in Kokrajhar and Bassaigaon, saying, “You are aware of the trafficking of the 31 girls from the districts like Kokrajhar, Chirang, Dhubri, Goalpara, Bongaigaon. Salaam Balak Trust Childline managed to rescue girls with the help of police, crime branch, at New Delhi Railway Station. Though the girls were rescued, some political power managed to take them to the destined places at Gujarat and Punjab. The most shocking part of this incident is that Surendranagar Child Welfare Committee has passed an order to keep 20 numbers of girls in children’s home in RSSP Halvad, Gujarat, despite knowing that Child Welfare Committee of the source district is not informed about the movement of children of their district. Please do at the earliest to bring back our children to Assam for their best interest.”

After this, the CWC, Kokrajhar, wrote a letter to CWC, Surendranagar, on June 22, 2015, to request the restoration of the children from Assam. The CWC, Surendranagar, never responded. In fact, the only letter (CWC/SNR/150) they wrote was on February 2, 2016, eight months after CWC, Kokrajhar, requested them to restore the girls to Assam. This was to D.B. Arthakur, member-secretary, Assam government, to “send home study of 20 girls from Assam” who are there at Rashtriya Seva Sansthan Institue in Halvad in district Morbi.

Halvad is a small town, previously in Surendranagar district, now in Morbi district, and lies at the southern edge of the little Rann of Kutch, 100 km from Ahmedabad in Gujarat. According to the JJ Act, the home study of any child—basically, a report on the child’s family and socio-economic background—has to be handed over to the CWC before it orders her to be sent to any government or NGO-run children’s home. In this case, the CWC, Surendranagar, had ordered the police to escort the girls to the Rashtriya Seva Sansthan without the home study report on June 3, 2015.

***

It is 6.45 am on a hot June morning in Halvad. The Saraswati Shishu Mandir campus is abuzz with young children measuring the distance of the building corridor. There are a number of young girls who are playing in the unkempt fields of this institution. I show a clipping of the June 17, 2015, Gujarat Samachar that mentions the adoption of 20 orphans of Assam by the institute to Sunita, the music teacher at the institute. I tell her that I want to meet these girls.

She points out a group of young girls playing in the courtyard. Divi, Ambika, Bhumika, Babita, queue up to talk to me.

Sunita tells them, “Babita, tell her your favourite story.” Babita is tutored. “The Rani of Chhota Kashi?” she asks her teacher, who nods agreement.

Tribal girls from Assam taking part in prayers

“Once upon a time, there was a brave king and a pious queen who lived in Chhota Kashi. Each morning, they would wake up, take a bath and pray to Shiva. They would dutifully wash the Shivling, chant the Gayatri mantra and meditate. This pleased Shiva so much that he blessed the rani with good clothes, several able sons and nice jewellery. The raja was blessed with a mighty army and a prosperous kingdom.” As she narrates the story, next to a small white marble temple with a framed portrait of Goddess Saraswati, several other girls surround her.

Babita continues with her story: “They were living happily when one day, the peace was disrupted by Khan, the Sultan of Gujarat, who attacked their kingdom. He killed children and animals, broke temples and chhatris of the ancestors, kidnapped women and young men.” From the narration, one could tell that Babita has heard and narrated this story several times. She could enact fear at the mention of Khan’s name and shudder while describing the killing. She makes for an impressive storyteller.

“To save his kingdom, the king decided to put the sultan in his place. As he left, he announced to his kingdom that the flag in the battleground will only be lowered if one of the two kings dies in the war. He made the rani promise that if he dies, they should not allow themselves to be defeated by the cruel invader,” she says.

Pointing vaguely in the air, she continues, “Days passed by as the rani waited in the Ek Dandiya Mahal, day and night, to keep an eye on the battlefield. And then one evening, the Chhota Kashi flag lowered. Rani did not take a minute to run down to the open field. ‘The invader must be coming any minute,’ she told her daasis (servicewomen). To save the honour of her husband and her motherland, they must end their lives instead of giving a chance to the enemy to defeat them. Huge piles of wood were collected and set on fire. Ghee and havan saamagri were added to it to make the biggest bonfire possible. The rani jumped and then the others followed. As they burnt, the whole kingdom gathered to witness their supreme sacrifice,” she sighs. She’s now a product of ideoogy, not reason.

“That evening, the raja returns. The rani and others had been reduced to ashes by then. The king was distraught. The previous evening, the flag was lowered by mistake. How could he forget that the rani always lived by her word. Heart-broken yet determined, he returned to the battlefield. Even the gods cannot avoid a determined woman who cares for honour. The Rani of Chhota Kashi had impressed Shiva with her supreme sacrifice for preserving her motherland’s honour. That day, he fought with such might and bravery never witnessed before. He continued till every single soldier of Khan’s army was reduced to dust and the sultan ran away. That day, the happiness of Chhota Kashi was restored. Since then, Shiva guards every nook and corner of Chhota Kashi. No outsider can disturb its peace and honour. The rani still comes to the Ek Dandiya Mahal every pooranmasi to check on everyone.”

Halvad is also known as Chhota Kashi. It’s known for its annual laddoo-eating contest, organised by the dominant Brahmin community, and its paliyas, stones commemorating the jauhar by ranis of the town, like the one in Babita’s story.

***

It is 7.15 am. All the girls run to the hall for the morning assembly. The assembly hall has a big stage and pictures of Hindu gods and goddesses, Gandhi, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Hedgewar, Savarkar, Shivaji, Jijabai and Bharat mata with a saffron flag all over the walls. One picture describes the tenth Sikh guru, Guru Gobind Singh, as “Hindu dharmarakshak”. The assembly hall has 60 young girls lined up on the right and close to 30 young boys on the left.

A small altar under the stage has an ‘Om’ sign, a picture of goddess Saraswati, and another of Bharat mata with a saffron flag. A teenage girl walks up to the altar to light a lamp as the assembled children sit cross-legged on the ground, their arms folded. After the incense sticks are lit and moved in circles around the three picture frames, Sunita, sitting on the left side of the gathering, breaks into the Gayatri mantra as she plays the harmonium. The children attempt to repeat in unison, eyes closed, “Om bhur bhuva svaha....” Four-year-old Devi, a Bodo girl from Goalpara, sitting right in the front, has one eye closed tight, the other peering at Sunita in an attempt to lip-sync the mantra, difficult for a four-year-old to get right. The other girls giggle as I catch her at her attempt to keep up with the prayer. A few more mantras follow after this, before Suneeta asks everyone to get up and stand at attention. She then leads them in singing ‘Vande mataram’.

Ghanshyam Dave

After the half-hour-long assembly is over, I request Suneeta and a few other adult attendants to allow me to speak to the 20 girls. Nineteen out of the 20 from Assam are asked to wait in the hall while others leave. I ask them, in Hindi, for their names—Suneeta repeats the question in Gujarati. They reply, turn by turn, “Ombika, Babita, Morobi, Divi, Sorogi, Suragni, Sukurmani, Riyajajot, Suriya, Neha, Bhumika, Sushmita, Sushita, Rani, Gujila, Rumila, Surmila, Devi, Mulita.”

Most girls only understand Gujarati now, since the medium of education is primarily Gujarati, although they are encouraged to speak Hindi. Back home, in Assam, they spoke in either Bodo or Assamese.

I ask Sushita, “Do you want to go home?” She nods. Sunita asks her sternly, “You want to go home?” “No,” she says, staring at the carpet.

I ask Divi which class she studies in.

“The bhajan class,” she says. I look to Suneeta for coding. She tells me these kids are new, so some of them haven’t been allotted a class.

“And you?” I ask Ombika. “We’re learning sanskaar,” she says.

“Like?” I ask.

In terse Hindi, she answers, “Honour of a woman, honour of the motherland, praying every day and saving the animals by not killing. Even for food.”

“Save your honour from whom?” I ask.

“From invaders. Who attack Hindus. Like Bangladeshis and missionaries in Assam,” she answers.

“Did you practice Hinduism at home?”

Sushita butts in, “We did not know that we all are Hindus. Krishna’s wife Rukmini was from our tribe.”

On December 7, 2014, after the flagging off of the Gyanodaya Express, Delhi University’s annual ‘Train of Learning’ to the Northeast, RSS joint general-secretary Krishna Gopal spoke of the Indian motherland and its links to the Northeast, focusing on Hindu gods and Hindu freedom fighters. “Lord Krishna’s wife Rukmini belonged to an Arunachal tribe,” he told them. In the same lecture, he narrated the story of the valiant Naga woman freedom fighter, Rani Gaidinliu, who fought against conversion of Hindus to Christianity. The message was clear—that if you’re from Northeast, you are Hindu—and it is being clearly indoctrinated in these young girls in Halvad.

I specifically ask Babita, “But don’t you like the non-veg food at home? Crab curry and pork?” Babita nods. “But a good Hindu girl should not touch maas.” The young girl’s likings have been slaughtered at the altar of a homogenised Hindu rashtra.

This conversation was paused when a guard came to tell me the trustee of the school, Ghanshayam Dave, has asked not to talk to the girls or take any pictures. I agree and offer to leave. As I get in the car, the gates of the institute are locked. The guard walks up to say that till Ghanshyam Dave arrives, I am not allowed to go.

I call Dave on the phone number provided by the guard, which goes unanswered. After an hour of waiting in the corridor, I tell the guard I am leaving. He stands in front of the car and refuses to budge. I tell him I have a flight to catch to Delhi but he said he will not let me out. I tell him he cannot stop me and I will call the police. He says, “You don’t know who Ghanshyam Dave is. Call the police if you want to.” Sikander, my local taxi-driver, tells me: “Ghanshyam Dave’s brother is a BJP member and his other brother is in the police.”

Meanwhile, Ghanshyam Dave, rides in on his bike in a starched kurta-pyjama and a tilak. He is in his fifties. He asks me to walk to his office and takes my business card.

“What have you come for?” he asks.

I tell him I wanted to know more about the adoption of the 20 girls from Assam.

“You know, two girls from Meghalaya ran away from the hostel three days back. We have yet not been able to trace them. That is why the guard was stopping you,” he says in an upset tone.

“I understand.”

“These girls were orphaned in the Assam floods. I was in Delhi when Mohan Bhagwatji asked me to take them to our institute here. We agreed,” he says.

After verifying my details, place of work and googling my blog, Dave says, “After all, you are a Brahmin. You won’t harm us.”

I did not confront his characterisation of me and get up to take leave. The wall in his office has a few framed certificates. The first one is from Vasuben Trivedi, MoS for women and child development, Gujarat. It’s dated June 23, 2015, and laudatory: it says the institution was inaugurated by Modi in 2002 and is a “pride of the state”.

The other is from the directorate of social defence, Gujarat, certifying the registration of the Rashtriya Seva Shikshan Seva Pratishthan, Halvad, under the Juvenile Justice Act for keeping children needing care and protection. The certificate has expired—on March 3, 2016. Under the Juvenile Justice Act, needy children can only stay in a registered home with current validity. Ghanshyam Dave clearly has support of the BJP-led Gujarat government.

Part 4:‘Those Nimn Jaati Girls’

If they want to help children, why not in Assam?

Officials inspect the Patiala children’s home

According to Article 30 (Children of Minorities) of the United Convention on the Rights of the Child, “Every child has the right to learn and use the language, customs and religion of their family whether or not these are shared by the majority of people in the country where they live.”

After Childline Delhi wrote to Childline Patiala on June 23, 2015, to enquire into the trafficking of 11 girls from Assam, Childline Patiala made a visit to Mata Gujri Kanya Chatravas near Sirhindi Gate in Patiala, Punjab.

After her visit to the home, where she and others were confronted and challeged by the caretakers, Harjinder Kaur, coordinator for Childline Patiala, filed this report: “After receiving the information from Childline New Delhi, Childline Patiala identified the location of the home named Mata Gujri Kanya Chatravas. Then we approached the chairperson of Child Welfare Committee, Patiala. He informed the district child protection officer and No. 4 Division Police Station to visit the home, along with Childline staff, to measure some important facts...like all 11 girls are there with proper safety etc. We reached the home together and interacted with the in-charge of that home and she denied to say something or call their higher authorities.”

“In the meantime, we visited the home thoroughly. There are 31 girls in this home. All the girls are school-going except 11 new inmates from Assam. It was found that there were no sleep beds in the home and mattresses were kept on the floor in a big hall. Meanwhile, some people from authority came and started arguing with us in rough language. We asked them, ‘Why did they not produce the girls before the Child Welfare Committee as per the JJ Act?’ and told them to produce some supporting document related to these 11 girls, but they did not show any authentic reason behind their shifting and started quarrelling with the chairperson, coordinator and DCPO.... Meanwhile, a person came over there named Mr Jindal, who is the member of CWC and a trustee of that particular home, and challenged us, ‘How dare you enter this home?’ and also tried to put political pressure on us. After the deteriorating situation, police personnel told us to leave the home immediately.”

Dr S.S. Gill, chairperson, Child Welfare Committee, Patiala, says the inspection visit he was part of indicated state connivance with a Sangh organisation, the prime example of it being that a Child Welfare Committee member is a trustee of this illegal set-up for children. He says, “During the raid in this girls’ home, the caretaker Veena Lamba and another member of the Sevika Samiti communalised the situation. They claimed that I, as a Sikh, was interfering with their religious institution. Some RSS member came and started threatening us. That is when we left.”

Shaina Kapoor, the district child protection officer who accompanied Harjinder Kaur to this home, confirmed that the hostel is not registered under the Juvenile Justice Act and that it is illegal to keep children in an unregistered institution under that Act. Fact is, this institution is registered only under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, meant for any literary, scientific or charitable societies. Most placement agencies that traffic children and women in the name of employment are registered under this Act.

Says Kapoor, “When we visited the home, there were neither bodyguards nor decent living conditions for these girls. They had no legal documents, no medical tests were conducted before keeping the girls, which is mandatory under law. Most importantly, it is illegal to bring children from other states for protection and care. If they want to help children, why not in Assam? They should instead be helping kids from Patiala. This is in violation of the law.”

Girls play the ‘Kashmir hamara hai’ game

After the case was investigated, Kapoor contacted a few parents of the girls living in the hostel. Parents of two girls, Monobina and Dibyajyoti, came from Assam. “These girls had been living in the hostel for two years and the parents were looking for them. When we asked the girls if they wanted to go home, they said ‘Yes’. They left with their parents. We have not been able to do so for the other girls, including the 11 from Assam, because of lack of cooperation from Mata Gujri Kanya Chhatravas,” she says.

Mata Gujri was the wife of the ninth Sikh guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur. Almost every fifth enterprise in Patiala is named after her. Even near the Sirhindi Gate, a heritage structure and Patiala landmark, there are at least three Mata Gujri schools and colleges. The Mata Gujri Chhatravas, too, is in the vicinity. There’s no way of peeking into the Chhatravas, which has a huge iron gate, shut tight. When we knock and enter, a middle-aged woman, Veena Lamba, comes to meet us. We are seated in the patio that is adorned by big posters of Laxmibai Kelkar, the founder of Rashtra Sevika Samiti, and Bharat mata.

Lamba introduces herself as the caretaker of the children’s home. She refuses to divulge any more information, and refuses to allow us to meet any of the girls. But she confirms there are 11 girls from Assam, and that Lakshmi, a Rashtra Sevika Samiti pracharika from Patiala, has gone to Guwahati to get more girls who will be handed over by Korobi.

“Do the Assam girls go to school?” I ask. She says, “Some of them do, but I cannot talk to you any further.” We left.

Next morning, at 6 am, we stationed ourselves atop the tallest building in the vicinity of the Mata Gujri Kanya Chhatravas. At 6.10, the girls started gathering on the terrace of the hostel. The saffron flag was put on a pole and the girls queued up in front of it. It was a Rashtra Sevika Samiti shakha. The saffron flag is the presiding guru. After a round of prayers, the girls started playing kho-kho. One game involved a girl standing inside a tiny chalk circle. She represents a terrorist from Pakistan trying to occupy Kashmir, while the other girls push her away from the circle, raising the slogan, “Kashmir hamara hai (Kashmir is ours).”

As we clicked their pictures, a neighbour walks up and says, “They are teaching girls from nimn jaati (lower caste) to do PT (physical training). Was there a dearth of beggars in Punjab that they had to bring these girls too to this place?”

Part 5: Ghar Wapasi For The Girls?

The Bodo and adivasis girls, taken away from their homes, have now embraced patriarchal ideas of honour, sati and jauhar

A tribal woman with a child near the Indo-Bhutan border

In her essay Truth and Politics, Hannah Arendt, a German-born American political theorist whose major work traces the roots of Stalinism and Nazism, wrote: “The historian knows how vulnerable is the whole texture of facts in which we spend our daily life; it is always in danger of being perforated by single lies or torn to shreds by the organised lying of groups, nations, or classes, or denied and distorted, often carefully covered up by reams of falsehoods or simply allowed to fall into oblivion.... Lies are often much more plausible, more appealing to reason, than reality, since the liar has the great advantage of knowing beforehand what the audience wishes or expects to hear.”

Babita has endorsed the narrative about protecting women’s honour from ‘outsiders’ without realising her own outsider status in Gujarat. Srimukti, disdainfully called an outsider and outcaste in Patiala, is playing a game fighting intruders in Kashmir. The narrative of throwing out intruders to save the Hindu rashtra is integral to the ‘education’ being imparted to the young tribal girls spirited away from home. Even when they themselves, ironically, become outsiders in the process.

The Bodo and adivasis girls, taken away from their homes, have now embraced patriarchal ideas of honour, sati and jauhar instead of turning to their own brave tribal women warriors like Tengfakhri, who fought criminals in the British era instead of committing suicide like the Rani of Chhota Kashi. The ‘bravery’ being instilled in these girls is limited to the Sangh’s Hindu state-building efforts as wives, mothers, recruiters and sometimes propagandists. They return home indoctrinated and embittered, their teenage rebellion channelised into radical religiosity.

In the last two decades, the Bodoland territory has seen high penetration by Christian missionaries. The SC order mentioned earlier in this report was an indicator of such involvement and trafficking of children. The Sangh parivar has emulated a similar model—and gone a step further—in a grand social agenda that seeks to ensure a permanent ‘Hinduised’ vote for the BJP, which, with its allies, has now come to power for the first time in the state. Sangh outfits have now created an atmosphere of terror to eliminate all possibility of dissent among grassroots activists.

A leading child rights activist from Kokrajhar says, “Prominent children’s aid organisations, such as Unicef, emphasise on improving social conditions within the children’s local setting, rather than uprooting them. But the RSS is arm-twisting activists and parents and brazenly flouting laws to send children away for indoctrination. Moreover, with the new BJP government at the Centre and in Assam now, no one wants to touch this case of trafficking of 31 girls as the RSS is involved.”

And he adds, laughing, “Guess this is the real idea behind PM Modi’s flagship programme for girls—Beti bachao, beti padhao!”

Runumi Gogoi, chairperson of the ASCPCR, says, “If they want to educate the girls, protect them and help in their overall development, why not undertake this noble cause in Assam? Why do they have to be taken to Punjab and Gujarat? It’s even more bewildering how these girls are not able to meet their parents, talk to them, if they are being taken away for education!”

In conflict-torn Assam, parents, young men and women and children resent their situation—there’s dearth of opportunity and development and poor penetration of state welfare. For the Bodos, there’s now a manufactured hostility to Islam and Christianity, and an artificially heightened hostility to the Santhals and Mundas. Encouraged by the Sangh parivar, institutions of family, religion and patriarchy push naive tribal girls and their parents into a path of indoctrination that encourages incessant conflict. Worse, it strips them of the power to exercise faculties not in line with the elite-caste Hindutva mainstream.

The truth of the trafficking of 31 girls by Sewa Bharati and Rashtra Sevika Samiti becomes either too fluid and complex to define or remains opaque. Which is why the destination states, BJP-governed Gujarat and BJP-Akali governed Punjab, violate laws and refuse to restore the girls from Assam.

Theba, Babita’s father, says, “We only wanted my daughter to study. Don’t the poor have the right to aspire to that without losing their children? How will Sewa Bharati build the rashtra by creating despairing parents like me who will die for not being able to meet their children?”

Timeline: Such A Long, Tortuous—And Illegal—Journey...

- June 9, 2015 31 tribal girls, between the age of three and 11, from five border districts of Assam are taken to Delhi on the Poorvottar Sampark Kranti Express

- June 11, 2015 The 31 girls travelling with Rashtra Sevika Samiti pracharika, Sandhya, rescued by Childline Delhi. They are taken to Paharganj police station. But on a dubious order from CWC, Surendranagar, and perhaps other pressure, the girls are still sent off to their eventual destinations.

- June 16, 2015 Assam State Commission for Protection of Child Rights terms it ‘child trafficking’ and against the Juvenile Justice Act 2000. Directs Assam Police, National Commission for Protection of Child Rights and others to bring back the 31 children to Assam for restoration to their parents.

- June 17, 2015 Ahmedabad edition of Gujarat Samachar publishes news that Saraswati Shishu Mandir in Halvad, which is affliated to Vidya Bharati Trust, adopted 20 girls who have been ‘orphaned during the recent floods in Assam.’

- June 18, 2015 Kumud Kalita, IAS, member-secretary, State Child Protection Society, Assam, writes to CWC, Kokrajhar and Gossaigaon, informing them that though Childline Delhi rescued the 31 trafficked girls with the help of police, some political power managed to take them to the destined place at Gujarat and Punjab. Expresses shock at CWC, Surendranagar, which passed an order to keep 20 girls in children’s home in Rashtriya Seva Shikshan Seva Pratishthan, Halvad, without informing the CWC of the source district. Asks several CWCs in Assam to bring back the children at the earliest.

- June 22, 2015 CWC Kokrajhar writes to CWC Surendranagar to request the restoration of the girls. CWC Surendranagar does not respond.

- June 23, 2015 Childline Patiala visits Mata Gujri Kanya Chatravas, Patiala. Find the home is illegal and the girls in abysmal situation. They are threatened and physically attacked by local RSS members.

- June 23, 2015 Vasuben Trivedi, Gujarat’s minister of state for women and child development, endorses RSSP Halvad for adoption of “20 orphan girls” from Assam. Calls it the ‘Pride of Gujarat.’

- February 2016 Probationary officer, CWC, enquiring about the 31 girls physically threatened by local RSS worker. FIR registered in the Gossaigaon police station in Kokrajhar.

- March 2016 CWC Kokrajhar informs the High Court and the CJM and district sessions judge, Kokrajhar, that affidavit filed on behalf of parents by Sangh outfits are false. Requests action. No response.

- July 2016 One year later, 31 girls still not back in Assam. Parents desperate.

The Law: Wrong Every Way And Breaking Every Law

Operation Beti Uthao clearly violates Indian and international laws and guidelines

- The SC in 2010 expressly directed “the State of Manipur and Assam to ensure that no child below the age of 12 years or those at primary school level are sent outside for pursuing education to other states.”

- Article 9 of United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child says, “Children must not be separated from their parents unless it is in the best interests of the child (for example, in cases of abuse or neglect).” India ratified the Convention in 1992.

- Article 30 (children of minorities) of the United Convention on the Rights of the Child states, “Every child has the right to learn and use the language, customs and religion of their family.”

- The Juvenile Justice Act 2000 states an NOC, home study report, case history and individual plan must be taken from the local Child Welfare Committee (CWC). The first option to rehabilitate any needy child is always with the parents.

- Needy children must stay in a protection home registered under the JJ Act 2000 with a legal validity. The girls are living in a home in Patiala that is registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860.

- The Juvenile Justice(Care and Protection of Children) Act 2000 (amended in 2006), states Child Welfare Committees have the same powers as a metropolitan magistrate or a first class judicial magistrate. CWC also has powers to hold people accountable for the child and to transfer the child to a different CWC closer to the child’s home or in the child’s state to dispose of the case and reunite the child with his family and community.