In conversations about Kashmir, scarcely any moment receives as much attention as the accession. Advocates argue that the settlement is a just and final one: the Maharaja ratified the accession, and Sheikh Abdullah, ostensibly the ‘undisputed leader’ of Kashmiris, supported it. Those who contest its legitimacy argue that neither of these figures represented the aspirations of Kashmiris. The Maharaja had, by 1947, been reduced to a cipher by sustained political agitation and mass uprisings. Abdullah, viewed with suspicion for his proximity to the Congress, swiftly fell into disfavour with Kashmiris for his role in securing the accession, and his initial insistence on its finality. Without the presence of the Indian army, and the J&K state’s own considerable capacities for coercion, Abdullah’s government would not have withstood the groundswell of political opposition. New Delhi’s policy has since remained one of foisting client regimes on Kashmiris, while repressing popular mobilisation and stymying the functioning of an independent political opposition. Virtually every election in Kashmir has been manipulated through fraud and violence to engineer outcomes favourable to New Delhi. This includes the elections to the Constituent Assembly, which in 1953 ‘confirmed’ the state’s accession to India.

Consistently denied a voice in the corridors of power, Kashmiris developed numerous ways to ‘speak’ outside them. In this piece, I look at three moments when the murmur became a roar. First, I discuss a mass uprising in 1931. Then I discuss a particular moment of mass mobilisation in 1963, coming in a period (1953-1963) when aspirations coalesced repeatedly around a call for self-determination. Finally, I discuss the formation of the Muslim United Front (MUF) and the electric impact on political opinion of the stolen election of 1987.

I. ‘Wazir tsalih, Kashir bali’ (When the wazir goes, Kashmir will heal). [Kashmiri proverb, recorded in the 19th century]

In July 1931, an assertive gathering of Kashmiri Muslims stood in open revolt against the Maharaja. On July 13, police fired at a protest, killing 21 unarmed people. What followed stunned the authorities. People, men and women, marched through the streets of Srinagar, carrying the dead. Described by one contemporary observer as an “elemental upsurge”, the crowds directed their force against the regime. While prompted by a deliberate insult to the Quran by one of the Maharaja’s soldiers, the uprising derived its force from deep wells of discontent.

Under the aegis of the British, who were keen on a friendly presence near the Central Asian frontier, the Maharajas enjoyed an unusual degree of latitude vis-a-vis their subjects. Under no compulsion to seek legitimacy from a majority, the Maharajas directed much of their patronage—land grants, public office and religious endowments—at Kashmiri and non-Kashmiri Hindus. Although not seamless, there was a significant overlap between class divisions and religious differences: the Maharaja’s support base lay among a small, predominantly Hindu, class of landlords and officials. Peasants and artisans, largely Muslim, laboured under a predatory and distressing tax burden—onerous taxes on manufacturing and professions, punitive land taxes and extensive enclosures of common lands. The collapse of the overtaxed shawl industry in 1870, a major loss of revenue, prompted a punishing escalation of the land tax, with disastrous consequences. In 1877-79, unremitting demands on a poor harvest led to a famine; the Valley lost two-thirds of its population to death and emigration. This was followed, starting in the early 20th century, by endemic food scarcity and soaring rural indebtedness. Between 1860-1930, the Valley had witnessed a major revolt by shawl-weavers in 1865, strikes by workers in the state-owned silk factory in the 1920s, and sustained agitations in Srinagar against moves to raise food prices or constrict supply (the grain trade was a state monopoly). These insurrections were contained by a policy of swift repression, and a stringently enforced ban on political activity. Nevertheless, people talked about politics secretly, organised covertly, and read smuggled political literature printed on presses in Punjab, many run by Kashmiris.

Also Read: The Cashmere Game

In 1931, several things conspired to shake the edifice. As the Valley felt the crushing impact of the Great Depression, news of religious insult catalysed simmering discontent into open revolt. Alarmed that events in Kashmir might stoke rebellion elsewhere, the British forced the Maharaja to constitute a grievance commission. The commission received a torrent of representations from Kashmiri Muslims demanding land rights, forest rights, religious freedom, education, employment, political freedoms and an accountable government. While reform was painfully slow, the lifting of the ban on political activity in 1932 allowed the emergence of the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference. Sheikh Abdullah was among the founding members, and soon its most popular leader. The party’s sharp rhetoric against the Maharaja, landlords and state officials won it a committed following among peasants, landless labourers and workers. The undemocratic political culture of the party, however, allowed popular forces little say in its direction. In 1938, Abdullah moved to transform the AJKMC into the National Conference (NC). This was presented as a discarding of religious considerations by the party, and many Muslim, Hindu and Sikh party members with socialist or secular leanings certainly meant it as such. Abdullah, on the other hand, was hoping to win support from sections of the Hindu elite. This gambit failed. While most Hindus saw their interests as tied to the Maharaja and remained hostile, the NC lost support among a large section of Muslims. His base slipping, Abdullah cast his lot fully with the Congress, violating a tacit agreement with other NC leaders to steer clear of both the Congress and the Muslim League. This was a move he would repeat: relying on powerful patrons in the face of popular displeasure.

II. ‘Yeh mulk hamara hai! Iska faisla hum karenge!’

In 1953, weary of Abdullah’s inability to quieten popular questioning of the accession, Nehru imprisoned him and replaced him with G.M. Bakshi. Marked by record levels of corruption and rent-seeking, and an especially violent turn in the repression of political dissent, Bakshi’s decade-long rule was brought to an end in 1963. On December 27, 1963, a holy relic—a strand from the beard of the Prophet—was stolen from the Hazratbal shrine. The outpouring of grief and rage that followed swelled into a mass upsurge, reminiscent in its force of the revolt of 1931. Despite the bitter cold, hundreds of thousands filled the streets day and night. As the conditions of the relic’s disappearance remained mysterious, restive protesters turned their ire against the Bakshi government. Demonstrators attacked properties owned by the Bakshi family, and also the state radio station—seen as an instrument of false propaganda. Offices, educational institutions and businesses were closed. The mood was an explicitly political one. Posters calling for a plebiscite appeared across the city. Slogans like Yeh mulk hamara hai, iska faisla hum karenge (this country is ours, we will decide its future) and We want plebiscite resounded in the massive processions that continued for days. Maulana Masoodi, a widely respected cleric and NC leader, was instrumental in preventing the emotionally charged demonstrations from taking a communal turn. While outrage at the theft of the relic fed into communal tensions in East Pakistan and Calcutta, fuelling riots in both places, anger in the Valley remained focused on Bakshi and his patrons.

Though these mobilisations ceased with the recovery of the relic on January 4, New Delhi was startled by the forceful and insistent call for self-determination. Hoping to forestall further unrest, Bakshi was replaced. In 1964, Sheikh Abdullah was released from jail to a hero’s welcome. Once incarcerated, Abdullah had begun to speak the language of self-determination. In 1955, the Plebiscite Front was formed by Abdullah loyalists who had been forced out of the NC. Led by Abdullah indirectly, over the next decade and a half the PF campaigned for self-determination, calling for a plebiscite under international auspices. This opened up a remarkable cycle of popular political mobilisations demanding a settlement of the ‘political question’. While the PF did not formally commit itself to any particular political future, Mirza Afzal Beg, Abdullah’s loyal lieutenant, would display a lump of rock salt wrapped in a green handkerchief at PF rallies, a potent insinuation, given that rock salt was mined in Pakistan and in short supply since the division of the state in 1947. Abdullah had never been more popular. Ultimately, he used these mobilisations as leverage in negotiations with New Delhi. In 1975, the Sheikh-Indira Accord was signed and Abdullah was made chief minister. Secure in power now, Abdullah clamped down on talk of self-determination. The question, however, persisted.

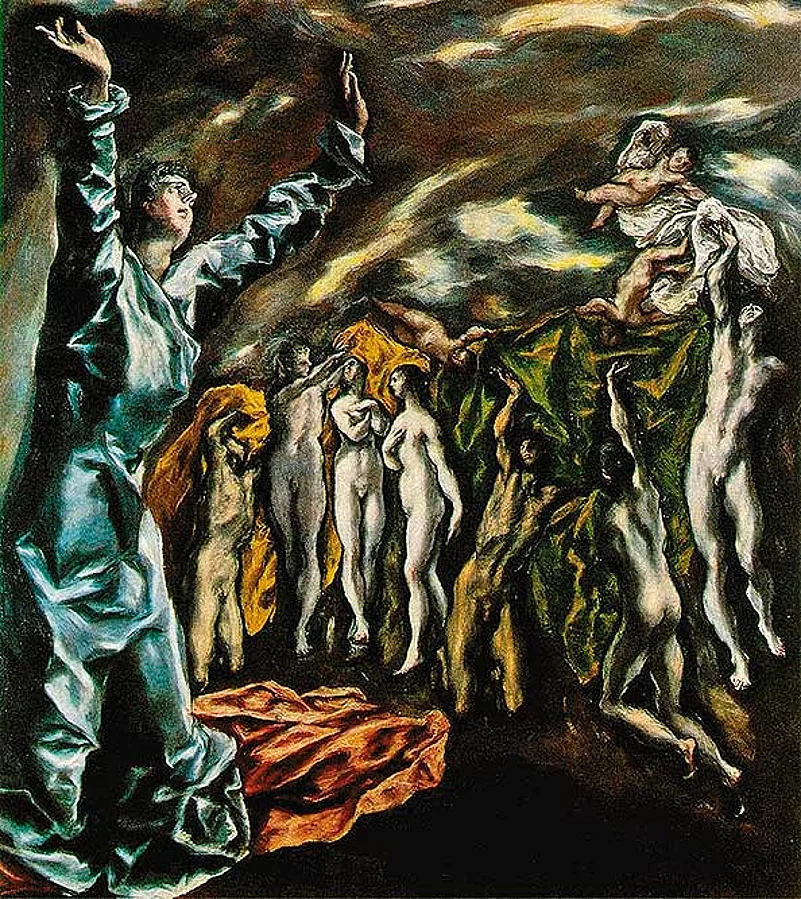

St John with martyrs in El Greco’s Opening of the Fifth Seal (1614)

III. ‘No election, no selection, we want freedom’

In the run-up to the election of 1987, the emergence of a political opposition independent of New Delhi announced itself in the form of the Muslim United Front (MUF), a coalition of 11 parties, ranging from secular to confessional, including the Jamaat-e-Islami. Upon his death in 1982, Sheikh Abdullah was succeeded in office by his son, Farooq Abdullah, who too was seen a client of New Delhi, much like his father. The MUF call for a settlement of the political question, economic development and an end to the Abdullah family’s rule drew an enthusiastic response. The election of 1987 saw a turnout of 80 per cent, the highest ever recorded in Kashmir. As was commonplace in Kashmir, election administrators blatantly manipulated results to favour the NC-Congress alliance, depriving the MUF of what would certainly have been a resounding victory. Despite MUF candidates leading by huge margins on several seats, NC-Congress candidates were declared victorious. While the MUF won 32 per cent of the vote even by the official count, it was declared victorious on only 4/76 seats, while the NC-Congress alliance ‘won’ the rest. Several MUF candidates and their election agents were thereafter arrested and tortured. The 1987 election conclusively demonstrated that New Delhi would not allow the question of self-determination to be raised through political institutions, and that even an organised and popular political force was powerless to change that. In the mass demonstrations that followed, millions rallied around slogans such as: “No election, no selection, we want freedom!” It is only after this election that the armed insurgency emerged as the most dominant and credible mode of pursuing a goal of self-determination.

India has adopted a combination of two modes of dealing with Kashmir: military and client regimes. Neither is working. Despite inestimable costs borne since the commencement of the counter-insurgency, the question of self-determination continues to resonate with Kashmiris, and continues to spin new meanings.

Also Read:

(The author teaches history at Jindal Global University. Views expressed are personal)