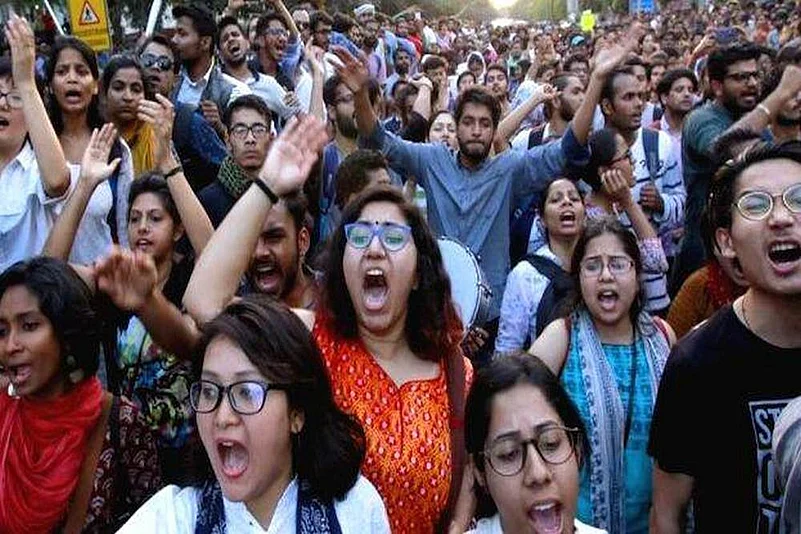

Few issues in the nation are more explosive at the moment than campus politics and activism. For many non-student citizens, it has come across as disruptive and dangerous. But the massive scale of protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019 (CAA) across the country has also revealed a real effort by left-oriented students. It also shows the increasing support from many campuses, not particularly known for political activism, including private universities and various institutes of technology and management.

What is the best way for student political activism to be effective, and also gain credibility and respect for citizens and policymakers across the nation?

Perhaps it is time to revisit that difficult question: Should student parties be affiliated to political parties outside a campus?

The fact that they do, leads us to some stark realities. Student wings of parties in power have a lot more resources than those of parties in opposition. In the recent decades, nothing has revealed this more clearly than the decline of a party like SFI, affiliated to the Left Front, now virtually extinct in campuses like the University of Delhi, just as its parent parties have withered on the national horizon.

But stark realities do not make for simple answers. The question of party affiliation for student politics is not easily resolved. It brings up an acute disharmony of opinions among students themselves, to say nothing of other stakeholders. Over the last week, one spoke to a number of students from different institutions and the division is loud and clear.

One clear argument in favor of political party involvement in campus politics is that the former helps students become aware of larger national issues. Such issues may very well lie beyond their immediate experience, but they are vital to the civic education and social conscience of any responsible citizen.

This was the opinion voiced by some students at a recent Baithak on student politics organised at Ashoka University. Especially, on this wealthy private campus, the concern was that without awareness of the outside world, brought in by political parties, apolitical student unions will lose touch with issues that do not immediately affect the privileged, who make up the vast majority of such universities.

But at the same time, many of the students, including many who have been active in the anti-CAA protests, said that they would prefer political parties not to play a role in their campus as their absence helps create a freer and more open forum of discussion.

A student from JNU highlighted the importance of the expertise students can bring to national politics. “Students are the ones who gets an opportunity to learn read and understand,” they said. “They have ideas and their knowledge can be used strategically to implement those ideas in the development of the country. Sadly as most our politicians haven't received quality education or come up with fake degrees they become ignorant to ideas with knowledge. So it becomes important for political parties to give that space to students wherein they can bring in their knowledge and help in implementation positively.”

A former Young India Fellow at Ashoka University pointed to the fact that it is often difficult to find safe spaces to discuss ideologically invested issues beyond the university. Hence the importance of political awareness on campus, which has historically produced many national leaders from the ranks of student leadership.

In spite of their overwhelmingly negative experience with “politically-affiliated student unions,” a student from the Bharat Institute of Technology in Meerut argued that such unions helped create a sense of social and political responsibility in students who might otherwise become narrowly focused on career and its “monetary benefits.” Student politics also offer the crucial “ground zero for capable leaders to jump start their political career, irrespective of their financial or social background”, as otherwise politics “lets in the privileged and the recommended.”

Just as many students, however, argued against party affiliation for campus student organisations. A student from Banaras Hindu University worried that a union with such affiliation would end up restricting its stand to the official party position on any given issue, which would be sad as a university student union should be open to students from a range of ideologies.

An alumni of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences accused political-affiliated student organisations of creating bitterly divisive politics on campus, while a former student of the Indian Institute of Public Health in Gandhinagar argued that political parties merely use student unions for their own selfish agendas.

There have been attempts to shape the character of student politics and elections so that they reflect the appropriate character of an academic setting. In the recent decades, perhaps the most notable of these come from the recommendations of the J.M. Lyngdoh committee (2006), which laid out rules for student elections to be conducted on college and university campuses. It stipulated strict rules about campaigns, including funds and auditing, eligibility of candidates, and restrictions on external influence and participation in campus elections.

But it became quickly clear that the Lyngdoh committee was too restrictive, its measures too draconian and unrealistic. Among other things, students are supposed to be the primary authority to conduct the electoral process, but the committee allows the university authorities to handle it. Many student unions have denounced these recommendations.

Most are easily flouted. A maximum of two hand-made posters per campaign? How realistic are these recommendations, really? One look at student union elections across the country makes it clear that the recommendations of this committee have been dumped a long time ago by student bodies almost everywhere.

Perhaps it is time for a responsible government to revisit the idea behind this commission and come up with a set of fair and practical guidelines? Political activism by students have held up a beacon of hope and conscience across the world – examples from countries as wide apart as Chile and Hong Kong have shone this light in the recent past.

India will be richer if political activism on campuses gains greater effect, respect and credibility. For that, we need to rethink the larger relationships that govern student politics – and the manner in which such relationships are conducted on campuses across the nation.

(With research inputs by Harshita Tripathi. Saikat Majumdar writes about arts, literature, and higher education and is the author of several books, including, College: Pathways of Possibility. @_saikatmajumdar)